“Just like positive thinking, advocating self-care has become yet another way to blame women for not fitting into the cheerful, uncomplaining, compliant, utterly in control stereotype that keeps everyone else calm and happy.”

Julie Norem, is a Wellesly College Professor of Psychology who co-manages the Negateers Facebook page along with Barbara Ehrenreich, myself and others. This issue of Quick Thoughts is organized around her recent post on the Negateers page.

I admit that the politics and commercialism that is been recently associated with self-care had been off my radar for too long. Julie puts me back on the issue.

I admit that the politics and commercialism that is been recently associated with self-care had been off my radar for too long. Julie puts me back on the issue.

Julie’s sharing of her thoughts sent me Googling and I came up with some great material, such as Christina Silva on The Millennial Obsession With Self-Care . Silva notes:

Today, self-care, as it’s defined by Gracy Obuchowicz, a facilitator and self-care mentor and coach in Washington, D.C., “assumes that we’re OK as we are and we just need to take care of ourselves … Self-care alone is not enough. You need to have self-awareness too. Self-care plus self-awareness equals self-love.”

While self-care has been around for centuries, it has only recently been co-opted by stars such as Solange and consumerized into self-care kits.

Let’s get right to Julie’s comments:

I’ve begun to hate the phrase “self-care.” Yes, it is really important to take care of yourself–to get enough sleep, to get enough exercise, to get appropriate amounts of nutritional food, and to find ways to de-stress that work for you. It *can* be a way to give permission to those who devote themselves to others to spend time on themselves without feeling guilty. But it can also become just another obligation (“you can’t take care of others well if you don’t take care of yourself”) or accusation.

Just like positive thinking, advocating self-care has become yet another way to blame women for not fitting into the cheerful, uncomplaining, compliant, utterly in control stereotype that keeps everyone else calm and happy. Admonitions, “helpful” advice to “make sure to find time for self-care” given to someone under pressure, already struggling to manage daily life, to cope with illness or a heavy workload, isn’t helpful. It just adds to the pressure, and carries the clear implication that this is (another) domain of failure for those who already feel at their limit. Adding insult to injury, suggestions for self care often include “getting a mani-pedi,” or “having your hair done.” Some women enjoy and find those activities relaxing. That’s fine, of course, and if that’s the case, they qualify as self-care. But many women don’t find those activities relaxing or enjoyable (or affordable), and only do them because they are an expected part of keeping up one’s appearance–a demand placed on women so much more strongly than on men. I think we need to be much more thoughtful (and I don’t mean mindful) about this concept.

Jordan Kisner delivers a smashing critique of self care to wrap up the long read The Politics of Conspicuous Displays of Self-Care

Jordan Kisner delivers a smashing critique of self care to wrap up the long read The Politics of Conspicuous Displays of Self-Care

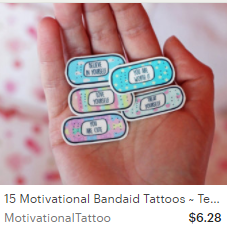

“Self-care” rose as collective social practice in 2016 alongside national stress levels. Articles about the art of self-care proliferated to the extent that_ _The Atlantic ran a guide to online self-care guides. The Times Style section published a think piece on the popularity of the term, which peaked in Google searches the week after the election. Suddenly, one could buy not only a 2017 Self-Care Planner but “self-care temporary tattoos” in the shape of Band-Aids bearing reassurances like “This too shall pass” and “I am enough.” In late November, a group of gamers and programmers participated in an online “Self-Care Jam,” in which they made affirming ephemera for the Web, including a video game intended to teach people to take care of themselves in the morning and a @selfcare_bot that tweets hourly affirmations (“No matter what, you need to do what’s best for you”).

And

The irony of the grand online #selfcare-as-politics movement of 2016 is that it was powered by straight, affluent white women, who, although apparently feeling a new vulnerability in the wake of the election, are not traditionally the segment of American society in the greatest need of affirmation. Naturally, the movement has become a market. Further investigations of Papaya Girl showed that her picture was #spon, or sponsored—in this case by a beauty company. In fact, #selfcare is often #spon. When I looked closely at another post, of a blogger having coffee and enjoying a “smooth and balanced” moment, I saw that it was paid for by McDonald’s to promote its new “smooth and balanced” coffee blend. A survey of one recent morning’s Instagram and Pinterest posts turned up an image by West Elm showing a kitten napping on one of the company’s quilts, an ad for Schick Hydro Silk razors, and a link to an article on five-minute “self-care moves” sponsored by eBay, with hyperlinks to essential oils and books of Mary Oliver poetry available for purchase.

Finally

Finally

Perhaps it is not surprising…that beneath the face masks and yoga asanas, many of the #selfcare posts sound strangely Trump-like. “Completely unconcerned with what’s not mine” is a common caption. So is “But first, YOU,” and the counterfactual “I can’t give you a cup to drink from if mine is empty.” I recently spotted another hashtag right next to #selfcare: #lookoutfornumberone. The image was an illustration of a pale, thin girl with a tangle of wildflowers growing from the crown of her head, reaching up with a watering can in one hand to water her own flowers.

More about Julie Norem

Julie’s The Positive Power Of Negative Thinking at Amazon

If you liked this post, you might also like McDonaldization of Positive Psychology: On tour with Marty Seligman

Advertisements Share this: