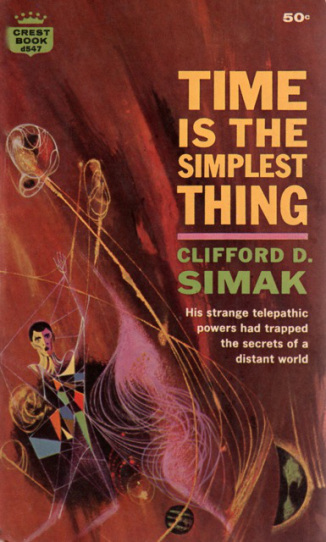

Time is the Simplest Thing is the fifth book by Clifford D. Simak that I have read. It was published in 1961, I read the Crest 1962 edition with Richard Powers’ artwork on the cover. I keep working my way through Simak because I agree with the consensus that he is one of the best “vintage science fiction authors.” Since January is, as everyone knows, Vintage Science Fiction month Twitter Feed I took advantage and started 2018 off with another Simak. (Cp. origin of Vintage SciFi Month)

Time is the Simplest Thing is the fifth book by Clifford D. Simak that I have read. It was published in 1961, I read the Crest 1962 edition with Richard Powers’ artwork on the cover. I keep working my way through Simak because I agree with the consensus that he is one of the best “vintage science fiction authors.” Since January is, as everyone knows, Vintage Science Fiction month Twitter Feed I took advantage and started 2018 off with another Simak. (Cp. origin of Vintage SciFi Month)

Compared with the other four novels of Simak’s that I have read, this one came across as far more aggressive. Simak is a very good writer, which is again demonstrated in this novel. Simak sometimes touches on social issues in his works – not quite to the extent of Poul Anderson – but one gets used to finding these elements in Simak’s fiction. This novel, though, seemed like Simak wanted to club readers in the head. Speculative readers might suggest that Simak was giving social commentary, particularly reflective of the time in which it was written and published. However, I think “commentary” is a bit loose of a word. Simak’s commentary, then, is quite heavy-handed and forceful. More so than I am used to from him.

Another facet that I have decided is part of Simak’s style, are the multitude of plotline directions that occur in his novels. I think this generally works for Simak, but in each of the novels I have read, it did seem like there was a whole lot of different threads and the plot would 180° more sharply than I liked. And maybe, sometimes, I did not love the new direction the story took.

Another facet that I have decided is part of Simak’s style, are the multitude of plotline directions that occur in his novels. I think this generally works for Simak, but in each of the novels I have read, it did seem like there was a whole lot of different threads and the plot would 180° more sharply than I liked. And maybe, sometimes, I did not love the new direction the story took.

Telepaths, like the main character, can project their minds beyond the usual barriers of space and time. Shep Blaine is one of the telepathic explorers – he mentally/spiritually – is able to traverse galaxies and time and explore. He is in the employ of a corporation named Fishhook which capitalizes on the findings of telepaths like Blaine. So, immediately, I was comparing some elements of this novel to that of Frederik Pohl’s Gateway (a novel I really despise). The novels are similar with regard to a few elements, particularly the corporation capitalizing on exploration.

Chapter eight gives a brief overview of the “telepathic” ability. Simak blends it with a variety of esoteric history such as shamanism and medicine men, magic makers, etc. He does a very skilled job of juxtaposing the existence of these abilities with that of the history of science. Unlike the exhaustingly common polarization of science vs. religion/magic, Simak insists that these abilities are just as “science” as regular Enlightenment-style science. Anyway, the storyline explains that those who kept researching the “magic” science were dispersed about the globe. But:

Finally, a country with a heart – Mexico – had invited them to come, had provided money, had set up a study and a laboratory, had lent encouragement rather than guffaws of laughter. – pg. 45

So, from this laboratory, Fishhook was born. Allegedly, it starts out with a focus on study and research. But, naturally, it eventually gets corrupted or, let’s just say, its purpose seems to be a little less about knowledge and a little more about control and economics.

By every rule of decency, parakinetics belonged to Man himself, not to a band of men, not to a corporation, not even to its discoverers nor the inheritors of its discoverers – for the discovery of it, or the realization of it, no matter by what term one might choose to call it, could not in any case be the work of one man or one group of men alone. It was something that must lay within the public domain. It was a truly natural phenomena – more peculiarly a natural phenomenon that wind or wood or water. – pg. 140

Shep Blaine is an employee of Fishhook and we meet him as he is on one of his space explorations. He has encountered an alien lifeform:

It was pink; an exciting pink, not a disgusting pink as pink so often can be, not a washed-out pink, not an anatomical pink, but a very pretty pink, the kind of pink the little girl net door might wear at her seventh birthday party.

It was looking at him – maybe not with eyes – but it was looking at him. It was aware of him. And it was not afraid of him. – pg. 6

I am at a loss for words about that pinky paragraph – I have not read anything like that in awhile and thought any good review of this novel should include that segment. Anyway, here is the essence of difference between a pulp novel and a literary novel – painted in very broad strokes. A pulp novel, from here on out, totally focuses on the alien and Blaine and they have adventures or horrors or action. There is a mystery or a challenge and there is a great deal of rushing around resolving it. In a literary novel, its all well and good to meet up with unheard of lifeforms and interact with them. But those engagements seem to be something of a context rather than a focus. Simak is not pulp, so early on in the novel, even though there are a few moments of escape/evasion, the majority of the novel is “social commentary.” Utilizing the elements of space exploration and alien lifeforms and whatever is seen as “science fiction” to drive satire or comment on or even as an allegory for present-day scenarios.

I have said before I do not love agenda fiction. I would not classify Simak as such, though, because even in his social commentary he serves up a tasty and intriguing story. However, I wonder what two versions of the novel would be like. One version is this one, complete with social commentary and thoughtful allusions. Another version being the one that follows the fun and pulpy storyline exclusively. I want both, but if I have to pick just one, I do think this is the better choice. I cannot help but admit I miss the action adventure novel, though.

Another fact: time travel – no matter how defined – is quicksand to science fiction writers. The concept draws them in and then they just sink in a muddied mire. I am not saying that this novel is about time travel. Not at all do I say that. I do say, however, that Simak does enjoy playing with time in his novels. Particularly in Time and Again. But in the middle of this one, there is an explanation that Simak gives that impressed me a lot. I loved the way the situation was described and I appreciated Simak’s explanation.

This was the past and it was the dead past; there were only corpses in it – and perhaps not even corpses, but the shadows of those corpses. For the dead trees and the fence posts and the bridges and the buildings on the hill all would classify as shadows. There was no life here; the life was up ahead. Life must occupy but a single point in time, and as time moved forward, life moved with it. And so was gone, thought Blaine, any dream that Man might have ever held of visiting the past and living in the action and the thought and the viewpoint of men who’d long been dust. For the living past did not exist, nor did the human past except in the records of the past. The present was the only valid point for life – life kept moving on, keeping pace with the present, and once it had passed, all traces of it or its existences were carefully erased. pg. 65

This paragraph contains a sharp-minded and well-written concept of time. And I really wish all those authors who think they have a great idea about time/time-travel would read it. I like how this paragraph is haunting and shadowy – with a touch of sorrow. But also how it looks forward with an active and lively feel. I really liked this paragraph when I read it; I worked to imagine what Blaine was seeing.

Simak uses technology in his novel to round out the “future feel” to it. For example, dimensinos exist, which are something like virtual reality/hologram systems, even commonly in personal homes. And then Trading Posts sponsored by Fishhook possess something like pseudo-Star Trek “transporters” that allow them to offer merchandise without having it in physical stock and opening the trade globally. Believe the hype when they say science fiction comes up with the gadgets first!

Overall, this is a good novel. Readers expecting any pulpy alien-adventure will be disappointed. This one looks at humanity’s fear of the Other, the use and misuse of technology, the fear that ignorance breeds, the juxtaposition of persecutor and persecuted, and the control-factor of corporations/capital. The main character is fairly likeable, if a bit robotic. Readers who love vintage science fiction and who would like to read good 1960s offerings will enjoy this one.

4 stars

Advertisements Like this:Like Loading... Related