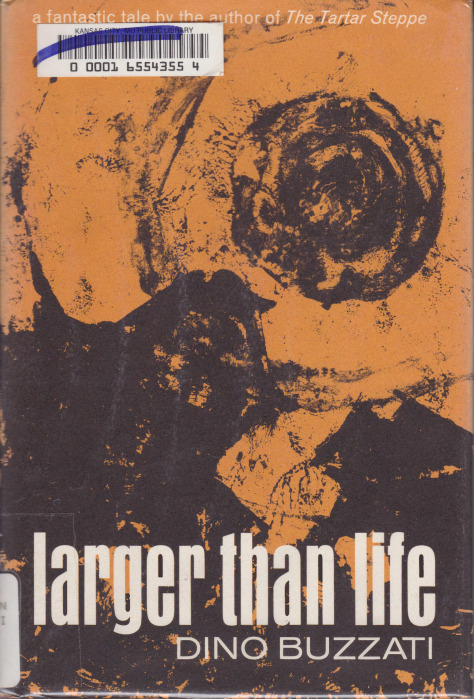

(Lena Fong Lueg’s cover for the 1967 edition)

3.75/5 (Good)

Dino Buzzati (1906-1972), best known for his masterpiece of Italian literature The Tartar Steppe (1940), was a central figure of the Italian avant-garde. He was a journalist, author, unabashed utilizer of genre tropes (graphic novels, SF, children’s fiction), and artist. Buzzati’s Larger Than Life (1960) is considered by some scholars to be the “first serious novel of Italian science fiction” (see 335-336 in the Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies).

Translated by the British poet Henry Reed in 1962, Larger Than Life applies Buzzati’s technique of direct, almost journalistic clarity, to a Kafka-esque scenario that is laid out in the first few paragraphs. In the prologue to the collection Restless Nights – Selected Stories of Dino Buzzati (1983) he describes his technique: “It seems to me, fantasy should be as close as possible to journalism. The right word is not ‘banalizing’ although in fact a little of this is involved. Rather, I mean that the effectiveness of a fantastic story will depend on its being told in the most simple and practical terms.”

Although not entirely satisfying, Larger Than Life should be read by fans of moody/well-written 50s/60s SF, non-English language SF, and Dino Buzzati’s other better known works. Unfortunately, copies are scarce and expensive online—I checked a few days ago and there were two copies priced at $90. I had the novel on my Amazon wishlist for years before a cheap $3 second edition appeared.

Spoilers throughout. Unavoidable considering the short length of the novel and centrality of the mystery and its implications.

Brief Analysis/Plot Summary

The mystery: Ermanno Ismani, a “Professor of electronics in the University of X” (5), is promised extensive financial reward to sign up for a secret project no one seems to know anything about. An official explains to a bewildered and frustrated Ismani desperate to know what he is signing up for: “there are times when the machinery of military secrecy reaches the paradoxical. Our task is to preserve that secrecy. What it conceals we must not concern ourselves with…” (10).

And so the Professor and his wife Eliza—“a priceless treasure for Ismani, himself so helpless in practical matters, and always upset at the slightest thing” (13)—head off into mountainous regions, “some faraway spot shut in by precipices” (17). And encountering the same layered, paradoxical, infuriating obfuscation regarding the nature of his assignment, Ismani concludes that they are truly “without any precise idea of what was actually going on up above them, on the plateau” (29). But the mysterious abounds—a mystery discussed ad nauseum by the guards below who regal Ismani and Eliza with tales of cryptic events: a befuddled Lieutenant Trozdem confesses, “Complete isolation: no women, nothing […] And yet… yet….do you know? No one wants to leave!” (29). Dogs are drawn to whatever exists on the plateau. And some claim to hear voices. A wall exists on the plateau, constructed by thousands of technicians and workmen brought in on shifts so they would not learn the secrets of the architectural form that stretches forth.

(Dino Buzzati’s cover for the 1981 edition of Larger Than Life)

Dino Buzzati, as in The Tartar Steppe, conveys the psyche of the soldiers stationed in this unusual rural landscape without knowledge of their purpose, in simple but effective strokes. Combined with Ismani’s growing sense that “[the mystery] was beginning to be grotesque, a sort of conspiracy devised to exasperate him” (49) the feel of the first half of the book is magnetic, taught.

Soon, almost too quickly, the nature of the mystery slips away as Ismani arrives among the scientists who work on the project. Endriade, the mad genius behind it all, cryptically admits: “at the same time, we might say that up here on the plateau we have a sort of… a sort of gymnasium for the training of mental faculties…” (52).

Buzzati’s descriptions of the building itself are sheer beauty. Description as poetical suggestion.

“Clearly, it was not a dwelling-place; not even, probably, a place where men could work. More like an immense lunar package, full of inanimate objects, machines for example, that needed no air or light; or, of course, some special kind of fortification.” (59)

….and unlike a tomb it “did not have that hermetic apathy” (59). And many of the architectural details take on implications of life, life among the concrete and mechanical. Convex glass windows suggest “lenses or like the pupil of the human eye” (59). A forest of small antennae, “clusters of filigree rapiers” (59), imply the collection of sense data. And of course the sounds, for inside the windowless construct “some intense form of life was going on” (60). Ismani, plagued with “obscure feeling” (66), cannot help but page through the associations his mind makes, a series of images, of order and connection, of nature and manmade substance, that “somehow this was an old acquaintance” (66). But it’s Eliza, not Ismani (too wrapped up in his electronics work), who smells out the true meaning of the city-like construct that lays across the plateau and reaches down into the alpine valleys and ravines and under its surface “a mysterious life was fermenting” (65).

Endriade confesses all, his plan to recreate Laura, a lost love, in the form of a mechanical city as human body, as repository for human senses, human emotion. His hand seems to caresses the landscape. “There. There.” (91) he gestures to Eliza who begins to see, “slowly, from the apparently chaotic jumble of walls, angles, geometric shapes, a physiognomy emerged, a characteristic expression” (93). A city with no overt human form, still offers “a tender and voluptuous gentleness” (93). And the sounds that trickle in an out, “a chorus of whispers, breathings […] tremors, slitherings,” all fragments of attempted communication (119).

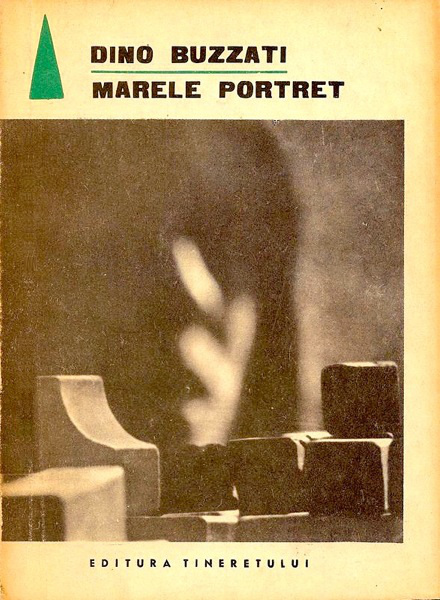

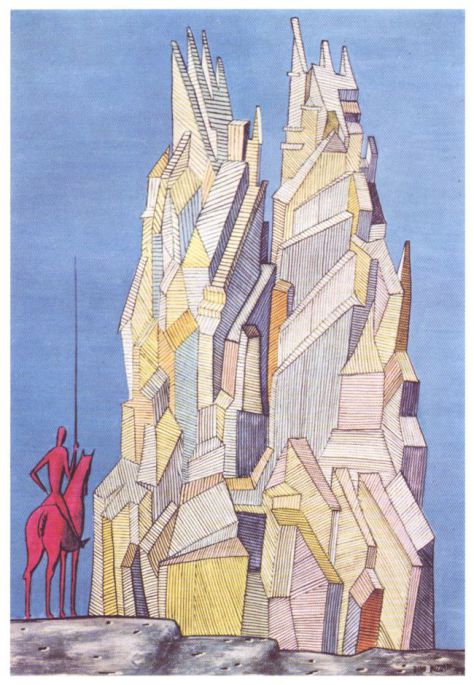

(Damian Petrescu’s cover for the 1969 Romanian edition of Larger Than Life)

But what is the nature of the automaton, Number One, “the immense artificial creature spread out over the landscape” (119). And more importantly, does it have a soul. Is it Laura?

Final Thoughts

Buzzati harnesses standard SF tropes in wondrous ways. As I’ve described above, the prose is crystalline and suggestive. It conveys character and wonder even if we’ve encountered all the parts before. The city as human physiognomy will dominate my memory of the book for it is in those moments that his journalistic ability to tackle the science fictional shine through. And as others have noticed (Clute at SF encyclopedia), Buzzati’s reluctance to imbue his discussion of manmade sentience with any reference to Judeo-Christian theology or practice makes the inevitable debates fresh.

I find myself torn and I’ve waffled back and forth in my ratings. As is so often the case, I lost the sense of paranoia and mystery the moment Elisa discusses Laura with Endriade. Unlike Lem’s Solaris (1961), which maintains the philosophical tenor and refuses to divulge all even as more about the sentient alien ocean comes to the surface, Buzzati does not restrain himself. He discusses mechanical intelligence, the nature of language, the nature of the human soul, in rapid succession.

However enjoyable the first two thirds were, at the end I wish more remained up on the plateau amongst the buttresses and geometric shapes.

Perhaps read The Tartar Steppe (1940) first. If you’re hooked on Buzzati (like I am), find a copy. If you want to read more well-written 60s SF in translation than this might also be perfect for you. Regardless, Larger Than Life deserves a reprint.

For more book reviews consult the INDEX

~

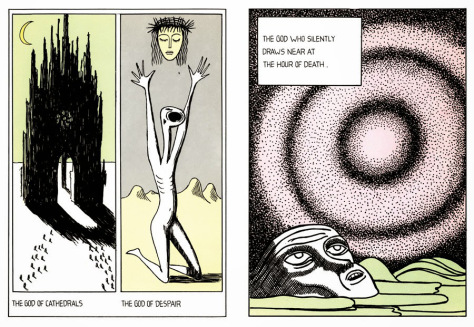

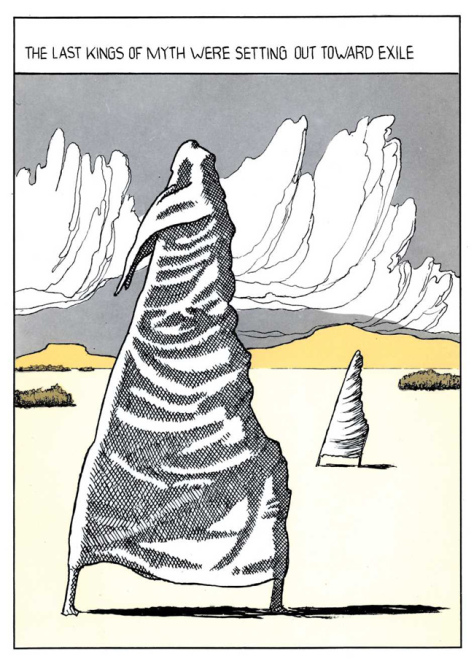

Note: Also in this post are some examples of Dino Buzzati’s art including scenes from his own graphic novel Poem Strip (1969)—which he wrote and illustrated. It was published in English by NYRB Classics in 2009.

For articles on Italian SF see the Special Issue in Italian SF, Science Fiction Studies (survey article is reproduced in full. The abstracts to the other articles are included.)

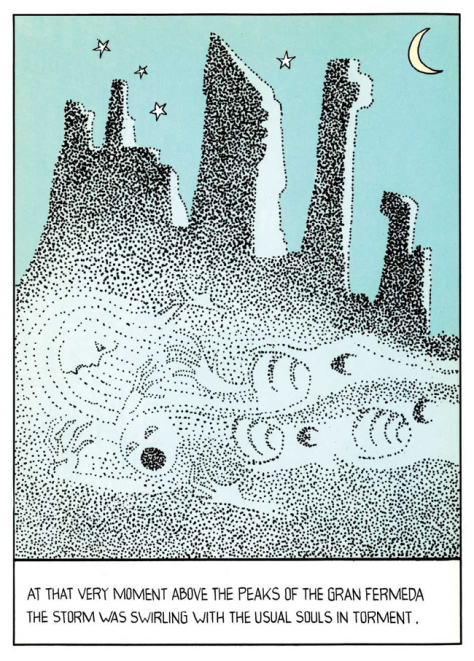

(Dino Buzzati’s art for his 1969 graphic novel Poem Strip) (Dino Buzzati’s art for his 1969 graphic novel Poem Strip)

(Dino Buzzati’s art for his 1969 graphic novel Poem Strip) (Dino Buzzati’s art for his 1969 graphic novel Poem Strip)

(Dino Buzzati’s art for his 1969 graphic novel Poem Strip)

(Dino Buzzati’s painting Piazza del Duomo di Milano, ca. 1952-58)

(Dino Buzzati, Gli apriranno, c. 1958)

Share this:

![[Hawthorn Tree Forever]](/i/cover.png)