I.

Last week, author and essayist Thomas Chatterton Williams wrote a full-scale assault of fellow writer and author Ta-Nehesi Coates in an New York Times op-ed entitled “How Ta-Nehesi Coates Gives Whiteness Power.” He makes the case as to why this country’s devotion to race as a construct will continue to perpetuate the deep divisions that have done nothing but metastasize under a Trump administration. There’s no two ways around it: this was personal. Not personal in the sense that Williams and Coates have beef, but rather that this was a critique of Coates’ performance in culture as well as his writing. I remarked, perhaps prophesied, two things would happen to Williams. The first was that black folks on social media were going to rip into him like he was the intellectual child of Clarence Thomas and secondly, that this essay was going to raise his profile. So far I’ve been right about both of these.

To know Williams is to know he wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post “Black Culture Beyond Hip-Hop” that felt as though it belonged in the pantheon of black intellectual conservatives such as Thomas Sewell and Stanley Crouch of the early 90s rather than for 2007. I didn’t discover Williams until later in 2010 when he wrote his first book Losing My Cool. I wrote a scathing review of it. I took issue with his point of departure in critiquing the cultural life of African Americans in this country. His heavy leaning on European philosophers to give critique rubbed me the wrong way. I read the book as though he needed to give himself justification for his education at Georgetown and permission to completely debase the experience of black students who attended Howard University across town. He only saw Howard as a party school compared to the studiousness he perceived at his own school. His retelling of that perception read as the epitome of black elitism, ignorant of his own class and skin privilege.

Since then, he’s made a living as an writer and essayist publishing in the Virginia Quarterly Review, Harper’s, The London Review of Books just to name a few and is working with The American Scholar. By all accounts, Williams is a good writer. I enjoy reading him even if I frequently disagree with him. His essays tend to have aspects of the personal all throughout which do a lot to engender to me his writing. His relationship with his black father figures prominently in life and in his writing. When he’s not writing about his life in Paris, he often focuses on the social construct of race finding a philosophical home in towering intellectual figures such as James Baldwin, but also Albert Murray and Ralph Ellison. His biographical essay that appeared in the New York Times Magazine on John Edgar Wideman shows his knack for plucking parts of black life out of obscurity to make commentary on the whole.

Williams has positioned himself as a long-form writer. That is to say, the substantive and more meaningful work around race that he produces isn’t reactionary, but intensely reflective. It requires interviews and research on the more time-consuming end or at least at the bare minimum, some amount of vigorous thoughtfulness. Remaining in the mix as a New York Times op-ed contributor, Williams received a lot of flak from his piece “The Next Great Migration,” including myself, as he argued that black Americans might find lands, if not free, but freer, from the racial oppression of the United States. It was a piece published in February 2015 and the wounds of Ferguson had yet to begin the healing process as Black Lives Matter was just beginning the process of igniting the spirit of resistance among black millennials. In other words, the zeitgeist of black Americans was that the fight was here on these shores and to leave would be a sign of defeat. In this instance, Williams fell victim to being painted as the black elitist. The fact that he was writing from the 9th arrondissement of Paris did not help his case.

Concerning the op-ed essay at question, Williams chose an extremely European point of departure. German to be exact. He opens with the concept of sonderweg to launch his critique against Coates. Whatever hope he had of winning any converts to his understanding of race was abandoned by the first paragraph. However, to Williams’ larger philosophical point, it shouldn’t matter what his point of departure is. But as many know, things like that do matter for a plethora of reasons. Mostly it has to do with the black American experience being suspicious of anything outside of it’s culture critiquing it. And very often for reasons that run very close to essentialism.

Williams writes that

Both sides mystify racial identity, interpreting it as something fixed, determinative and almost supernatural. For Mr. Coates, whiteness is a “talisman,” an “amulet” of “eldritch energies” that explains all injustice; for the abysmal early-20th-century Italian fascist and racist icon Julius Evola, it was a “meta-biological force,” a collective mind-spirit that justifies all inequality. In either case, whites are preordained to walk that special path. It is a dangerous vision of life we should refuse no matter who is doing the conjuring.

By the time the essay concludes, Williams has compared Coates and white supremacist Richard Spencer and you can hear the record scratches in folks’ heads trying to make sense of the argument. A comparison such as that is never going to rest well with vast sections of the black social media multiverse nor with many who are part of the black literati. While all of this may affect the sensibilities of many black readers, and even white liberals who are acolytes for Coates, all of it rings bankrupt because I’ve yet to see anyone appropriately deal with the crux of Williams’ argument concerning the fetishizing of race by both black and white folks.

For reasons one could cobble together from the body of his work, one can see how much of Williams’ philosophies on race are out of the mainstream. Coates, like William Jelani Cobb, his friend, and most others who I see on social media, be they well-known or not, see blackness as a fixed thing. There is an essentialist argument afoot. Essentialism stems from that notion that we can play the game of Clarence Thomas and Ben Carson not really being black, but Maxine Waters is undeniably black. Most recently one’s “wokeness” has been a stand-in for how black one is. This game of essentialism works for the daily ins and outs of life at home or at the family reunion, but when black intellectuals after the age of Obama—in all of his black complexities—continue to play that game, it gets old really fast. Williams is correct in that “so long as we fetishize race, we ensure that we will never be rid of the hierarchies it imposes.” He finishes by writing proleptically that “we will all be doomed to stalk our separate paths” if the fetishizing continues.

II.

In an interview for the New York Times, Coates, who lived in Paris for a year, remarked if he’d ever return said, “No, I can’t. The war is right here. The war is right here.” He moved his family to Paris very shortly after the publication of the immensely popular Between the World and Me in 2015. He returned back to the States with a fame he wasn’t prepared for. Planning to move his family to Brooklyn, he didn’t because of safety concerns due to his celebrity. He has been the darling of white liberals since his return. The way he talks about race has made him perhaps the most quoted black person on the topic in recent memory. Between the World and Me was a featured prop in a Saturday Night Live skit lampooning how white liberalism works in this country.

Consistently in interviews and talks, the white liberal response to Coates and his work is “So now what?” which is code for “What can I do?” Routinely, he is always asked does he have hope for America. He consistently responds that he has none. This pseudo-nihilistic approach—pseudo because if you have no hope, why did you return to the United States—works in the social contract with white liberals because he doesn’t require any action from them. Unless intensifying white guilt is intended to be punishment for sins, he almost lets white folks off the hook from actually changing anything.

Black intellectual heavy-hitter Cornel West saw this much in 2015 when he wrote on Facebook page that

Coates is a clever wordsmith with journalistic talent who avoids any critique of the Black president in power. Coates can grow and mature, but without an analysis of capitalist wealth inequality, gender domination, homophobic degradation, Imperial occupation (all concrete forms of plunder) and collective fightback (not just personal struggle) Coates will remain a mere darling of White and Black Neo-liberals, paralyzed by their Obama worship and hence a distraction from the necessary courage and vision we need in our catastrophic times.

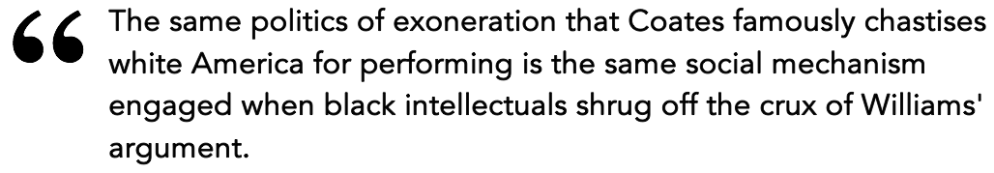

I’ll admit, I didn’t think this many black folks cared about Coates this much to defend him. Especially in the face of someone like Williams. I’m not even sure what they are defending ideologically or even what they’re defending against. The general advocacy of Coates has manifested itself in a dismissal of Williams, thereby completely side-stepping a deeper and reasoned conversation about essentialism and fetishizing race. Instead, those who blindly defend Coates fetishize him for the sake of maintaining this bogus racial contract for their own sake. The same politics of exoneration that Coates famously chastises white America for performing is the same social mechanism engaged when black intellectuals shrug off the crux of Williams’ argument. It’s the same process Coates engages self-reflexively to let himself off the hook as well.

I’ll admit, I didn’t think this many black folks cared about Coates this much to defend him. Especially in the face of someone like Williams. I’m not even sure what they are defending ideologically or even what they’re defending against. The general advocacy of Coates has manifested itself in a dismissal of Williams, thereby completely side-stepping a deeper and reasoned conversation about essentialism and fetishizing race. Instead, those who blindly defend Coates fetishize him for the sake of maintaining this bogus racial contract for their own sake. The same politics of exoneration that Coates famously chastises white America for performing is the same social mechanism engaged when black intellectuals shrug off the crux of Williams’ argument. It’s the same process Coates engages self-reflexively to let himself off the hook as well.

III.

You’d have to go back to the first-half of the 20th century to see black voices embrace divergence in thought. This was most exemplified amongst the black intelligentsia of the Harlem Renaissance. While blacks have continued their disagreement until the present, the stakes have changed. By the modern civil rights era, white dominated media outlets expected blacks to think singularly and somehow the idea that we, as blacks, must coalesce around the same ideologies, became conventional wisdom. The emergence of conservative black intellectuals in the 1970s as mainstream became fodder for white America to punt one against the other. The cracks in that dichotomy began with black women entering the fray, such as bell hooks in the 1980s, but the walls didn’t come down until world wide web made way for the democratization of information available to virtually everyone around the time of Obama’s first campaign in 2008.

In cooking, a reduction sauce is produced by boiling away much of the liquid and leaving a thickened sauce where essence of the flavor is amplified. The complexities of blackness are often reduced for the sake of easy public consumption. Having come across Imani Perry’s review of We Were Eight Years in Power she writes that “[Coates’] historical compositions are too facile. For example, Coates’ description of the history of black politics as a binary: liberal integrationism on the one side and socially conservative black nationalism on the other, gives too short a shrift to a long and varied political landscape.” This could be what bothered Williams to the point of writing an op-ed. So much of Coates’ philosophies on race are rooted in reductionist understandings of blackness that can ignore someone like Williams who identifies as black and has a white mother. Yet Coates can uncritically wax poetic about Barack Obama as black conveniently ignoring him being raised by his white mother. Such a reductionist approaches amplify the essentialist argument and ultimately, the nuances are boiled away. While I don’t think anyone was expecting a full-scale essay level response from Coates, to dismiss the argument and tweet about going to Comicon gave tacit sanction for, shall we say, some decided anti-intellectualism to reign supreme.

Suffice it to say, there is more than enough room for Williams’ and Coates to exist and breathe the same air in the same room. The insistence that blackness has to have one mode of public digestion is outmoded and absurd. The Twitter take-down of Williams was done by people who read think-pieces 500 words or less and listen to podcasts that have hosts that use elongated affirmatives–yaaaaaaas! While those same people are entitled to their opinions, it shows just how devoted folks are to the essentialist approach to race. Its disappointing when actual intellectuals—those who have shown themselves capable of reading and writing about things and ideas and not just people—participate in the intellectual-shaming of Williams. It’s fine if you don’t agree with him, but it’s not worth dismissing his intellect as a whole. The oddity of white folks tweeting against Williams is just even more evidence of how devoted we as Americans are to fetishizing race.

Post-racial usually has a negative connotation often associated with equally problematic phrases such as “I don’t see color” or an emphasis for a “color blind” society. However, what Williams is advocating is a dismantling of the hierarchal system, not an erasure of ethnic culture. Far too often those aforementioned statements are used in a way to whitewash blackness for the sake of Americanity. Its the same ideological stumbling block that has allowed NFL commissioner Roger Goddell to send a memo to all teams saying he wants all players standing for the national anthem, but never address the race specific reasons why the protests began in the first place. America first, black folks last. If at all.

What gives me the most consternation in the midst of the back-and-forth that I’ve watched on Twitter and Facebook is the inability for thinking folks to give Williams the basic benefit of the doubt. Perhaps I contributed to that some years ago in my own take downs of him. In my last post about him, I accused him of getting the race conversation wrong. This time he got it right. But I’d like to consider myself fair enough and give space for agreement; black intellectualism will die if we can’t make room to at least hear out each other. If I’ve said it once, I’ve lamented it a thousand times: the Internet is where nuanced conversation goes to die. Unsurprisingly, in an argument suggesting that the dismantling of the construct of race is the functional equivalent of ignoring race altogether, its clear we’re in a bad way.

Williams does the iconoclastic work of actually imagining a post-racial society if no other reason than his ability to name it ideologically. In his essay “Black and Blue and Blond” he writes:

If the point is for everyone to build ships, set sail, and be free, if we are collectively ever going to solve this infinitely trickier paradox of racism in the absence of races, we are, all of us—black, white, and everything in between—going to have to do considerably more than contemplate façades. An entirely new framework must be built. This one’s rotten to the core.

We should all be so bold and endeavor what this entirely new framework should look like.

Keep it uppity and keep it truthfully radical, JLL

Advertisements Like this:Like Loading... Related