Thesis: in Life and Fate there are only minor characters.

Yes, the family Shaposhnikova is at the center of the book. Yes, Viktor is modeled on Grossman and his fall from and return to political favour is compellingly detailed. Yet even the characters we might be tempted to call central feel secondary. Not because they’re imperfectly or casually developed. We know them well, get inside their heads, feel for them. Nor is it because the “hero” of the book is really some abstraction like the Soviet Union, or the Russian soul, or even the war effort.

Grossman learned from Chekhov how to draw us towards characters while also distancing us from them. (I’m thinking here of someone like Gurov in “The Lady with the Little Dog.”) Honestly, I’m talking through my hat here because I don’t know enough about Chekhov, but I do know Life and Fate reminded me of him. And that was even before one of the characters declaimed at length about Chekhov’s genius. (“Chekhov brought Russia into our consciousness in all its vastness—with people of every estate, every class, every age…. He said—and no one had said this before, not even Tolstoy—that first and foremost we are all of us human beings. Do you understand? Human beings!”)

This passage, in which some air force pilots who have been ordered to leave the village where they’ve been billeted decide to spend one last night on the town, as it were, reminded me of “The Kiss”:

Everything—the river, the fields, the forest—was so beautiful, so peaceful, that hatred, betrayal and old age seemed impossible; nothing could exist but love and happiness. The moon shone down though the grey mist that enveloped the earth. Few pilots spent the night in their bunkers. On the edge of the village you could glimpse white scarves and hear quiet laughter. Now and then a tree would shake, frightened by a bad dream; the water would mumble something and return to silence.

The uncertainty of who speaks the opening sentence, which gives way to the speculation that the narrator is ventriloquizing the collective sentiments of the pilots and thereby gently satirizing them (gently, gently, though: after all, so much suffering awaits them at the front: for most of them, old age really is impossible); the juxtaposition of the slumbering landscape and the sexual possibility of the evening’s entertainment, so reminiscent of the regiment’s nighttime walk from the country home past the brothel in “The Kiss”; that amazing and amazingly strange image of the tree “frightened by a bad dream”: all of this is pure Chekhov!

But I didn’t want to talk about Chekhov. I wanted to talk about minor characters. I said yesterday that Life and Fate contains dozens, even hundreds of characters. Some appear only once without serving any important narrative function. Yet Grossman makes them all vivid.

For example: In a scene just a few pages before the one I cited above, Lieutenant Viktorov is gathering his belongings in preparation for being deployed for active duty. The scene is ostensibly about the Lieutenant—whose lover is the daughter of one of the Shaposhnikova sisters—but he finds himself remembering the old woman he had been billeted with until just a few days ago, “a dreadful landlady, a woman with a high forehead and protuberant yellow eyes,” who filled her home with smoke in an attempt to get rid of her tenant:

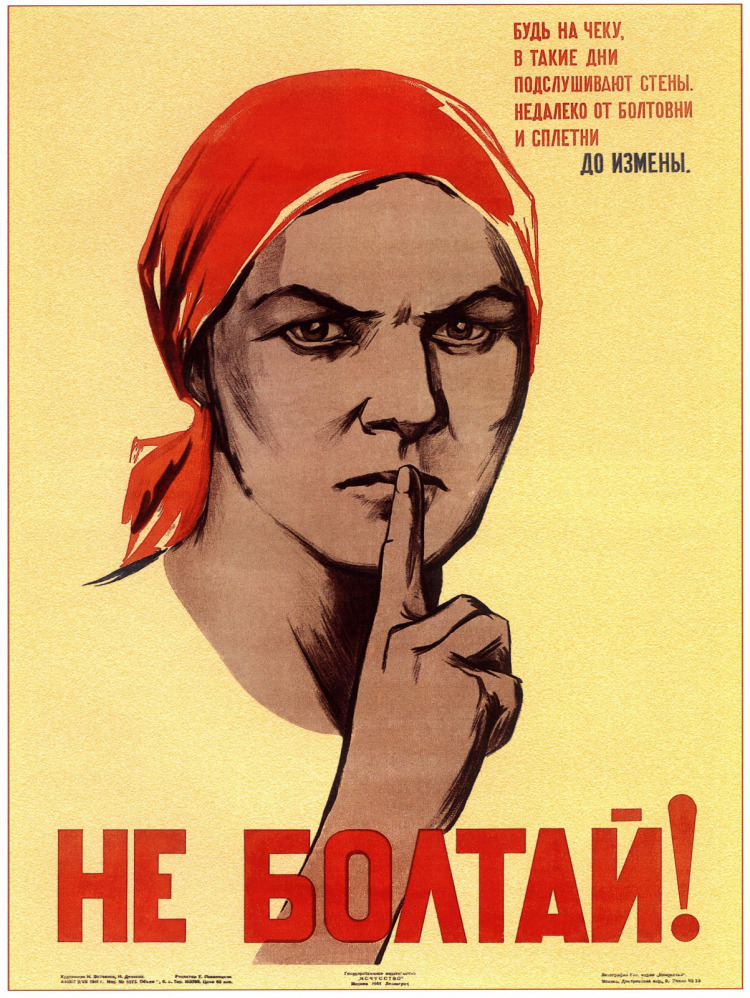

He walked past the hut Yevdokiya Mikheevna had smoked him out of; he could see her expressionless face behind the dirty window-panes. No one ever talked to her when she stopped for a rest as she carried her two wooden buckets back from the well. She had no cows and no sheep; she didn’t even have any house-martins in the eaves. Golub [the Lieutenant’s friend] had asked questions about her, hoping to bring to light her kulak background [which would allow him to denounce her], but she turned out to be from a very poor family. The women in the village said she had gone crazy after her husband’s death: she had walked into a lake in cold autumn weather and sat there for days. But she had been taciturn even before that, even before her marriage.

That’s the first and last we ever hear of Yevdokiya Mikheevna. But don’t you want more? What could be more Russian than sitting in a freezing lake for days crazed with grief? What’s typical here is the way a character who had seemed entirely one-dimensional—she is mean, stubborn, possibly disloyal to or uninterested in the war effort—suddenly gains unexpected depth. I’m not even sure why Grossman thought to include her. We don’t need to see the Lieutenant chased out of a billet by a disagreeable landlady. (And in fact we don’t; we only hear about it in retrospect.) The only function this anecdote seems to serve is to reinforce what a good guy Viktorov is—he doesn’t report her to the authorities even though his friend Golub wants him to.

So what is she doing here? Is she supposed to remind us of the suffering of the Russian people? Or is the brief, intense glimpse of her life story intended to allow us to recognize the transience of any given moment? Especially in wartime, people brush past each other, coming into contact in ways they otherwise wouldn’t, though that contact doesn’t necessarily lead to anything.

Thinking about it some more, I suspect what Grossman really wants from this scene is to remind us that Yevdokiya Mikheevna is a human being, with a past, with value, with her own reasons for her actions even though his novel can’t pause to make more of them.

It seems important that for Grossman humanity is best expressed through fiction. To understand the thing that (for him, at any rate) is most real we need recourse to a thing that is fake. But what happens when that fiction is based on real life? And especially when it includes real historical figures? Life and Fate famously includes a number of such characters, including German and Soviet military leaders, like General Paulus of the 6th Army, who we may or may not know, as well as the Heads of State that we surely will. Yes, Stalin and Hitler get their own brief sections, scenes in which they aren’t just mentioned or pass by in the background, but which are narrated from their perspective.

In thinking about these scenes I was reminded of the bit in S/Z where Roland Barthes, citing Proust on Balzac’s weighting of fictional and historical characters (in the Comédie humaine Napoleon is much less important than Rastingnac, say), notes that realist fiction must introduce historical characters only in passing:

It is precisely this minor importance which gives the historical character its exact weight of reality: this minor is the measure of authenticity… for if the historical character were to assume its real importance [if the novel was about Napoleon, or in our case, Stalin or Hitler, that is, made them central to the text, tried to get inside their heads, etc] the discourse would be forced to yield it a role which would, paradoxically, make it less real (thus the characters in Balzac’s Catherine de Médicis, Alexandre Dumas’s novels, or Sacha Guitry’s plays: absurdly improbable): they would give themselves away.

I think this is a pretty sound critique of historical fiction, and one reason why something like Hilary Mantel’s wonderful Cromwell novels work precisely because they are about Cromwell (little known) rather than about Henry—imagine them from the King’s perspective: impossible.

At any rate, some critics, I gather, have indeed found the Hitler & Stalin sections of the novel (they’re very brief, only a few pages each) absurdly improbable. I think it’s telling, and a further sign that Barthes is on to something, that Grossman does better with Hitler than with Stalin, because he’s much more familiar with the latter. It’s easier for Grossman to imagine Hitler as fully fictional, Hitler has much less reality for him; for this reason, his depiction of Hitler taking a solitary walk in the forest of Görlitz, near the border with Lithuania, and falling prey to a sudden terror (“Without his body guards and aides, he felt like a little boy in a fairy tale lost in a dark, enchanted forest”) is quite convincing. The final thought he gives Hitler, however—“For the first time, he felt a sense of horror, human horror, at the thought of the crematoria in the camps”—is not. Not because Hitler wasn’t human, but because this sentiment isn’t prepared for by anything that comes before.

The Stalin section is similarly kitschy: the Great Leader imagines “all those he thought he had brought low, chastised and destroyed… climbing out of the tundra, breaking through the layer of permafrost that had closed over them, forcing their way through the entanglements of barbed wire.” But this rather Grand Guignol vision of Stalin’s victim’s coming back to assault him isn’t the real problem with this section. Instead, the Stalin section fails because Grossman turns it into a meditation on all the future glories (“jetplanes, intercontinental missiles, space rockets”) and horrors (the oppression of Eastern Europe, the show trials of various writers and artists) that were to come after the war.

Unlike the other characters—unlike Viktor Shtrum, unlike Lieutenant Viktorov, unlike Yevdokiya Mikheevna—neither Hitler nor, especially, Stalin are minor enough.

Next time: Grossman’s lists.

Advertisements Share this: