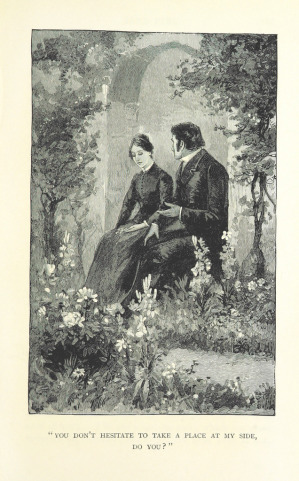

Years ago I fell in love with Jane Eyre. I remember deciding I should read it, then beginning, then forcing myself to stay strong through a beginning section I just didn’t quite get into. But then…just when I’d decided the reading was a lesson in patience and not much more, the story blossomed in a way that grabbed every bit of my attention. The story was beautiful. The emotions felt true. And the angst seemed real.

Years ago I fell in love with Jane Eyre. I remember deciding I should read it, then beginning, then forcing myself to stay strong through a beginning section I just didn’t quite get into. But then…just when I’d decided the reading was a lesson in patience and not much more, the story blossomed in a way that grabbed every bit of my attention. The story was beautiful. The emotions felt true. And the angst seemed real.

I’ve never really been alone in the world. I’ve never had my only friend die. I’ve never fallen in love with a man who, as it turned out, was married to a mentally ill woman he’d kept hidden from the world. I’ve never run away to nearly die on the moors, and I’ve never been taken in by a set of siblings who offered me a place to heal and grow.

But there are moments in that book, whole passages that ring of a deeper truth that touch my soul.

Laws and principles are not for the times when there is no temptation: they are for such moments as this, when body and soul rise in mutiny against their rigour; stringent are they; inviolate they shall be… Preconceived opinions, foregone determinations, are all I have at this hour to stand by: there I plant my foot.

And that is what I look for in Christian fiction. For a soul-stirring truth, albeit a truth that may be clothed in a package incredibly unlike me and my own experiences. There are moments in Jane Eyre when you can feel the utter angst, the dissatisfaction with the narrative world’s events – that things have not gone well for any character, but particularly for our heroine. But that path along the difficulty is the beauty that is offered.

The interesting thing is, my perception of any passage or even the novel in its entirety will differ greatly from another’s. Take a look, for example, at Elizabeth Rigby’s scathing review.

We are painfully alive to the moral, religious, and literary deficiencies…

And it’s here that I’d like to begin my discussion on the topic of “Christian fiction.” Jane Eyre is widely considered a work of great fiction. But there were still those who would not consider it that. The principle holds true for Christian fiction as well. While I will fully admit that most titles that fall in the genre of Christian fiction would not ever be considered great literature (by anyone, let alone many), I believe it has a distinct and worthwhile purpose for many readers. One worth exploring beyond a matter of simple personal tastes.

Christian Fiction and the need for authentic struggleChristian fiction can be simply defined as works of fiction that include an overtly biblical worldview and are traditionally light on violence, sex, and profanity. The fare routinely considered as the staples in the Christian market are works by authors such as Janette Oke and Jan Karon. If I were to speak of my own tastes, I might direct you to reads such as Ted Dekker’s Circle Series or perhaps Jessica Dotta’s Price of Privilege Trilogy. There are a wide variety of writings that fall into the category of Christian fiction. There are historicals, suspense, romance, speculative, contemporary, Amish. The list goes on.

I want to consider that each book that falls into the category of “Christian fiction” might just have an audience that finds it quite thought-provoking, particularly moving, and/or incredibly worthwhile. But the heart of what is needed in a successful story is the need for a wresting of true emotions. Certain individuals may identify in a greater capacity with emotions presented. Others may not react similarly. But the fact remains that if even one reader identifies with them and is moved by them, the piece of writing cannot be a failure.

This brings to mind a piece recently published at The Rabbit Room titled, “On the Possibility of Being Met in Winter” by Doug McKelvey. I appreciate McKelvey’s focus on the need for a raw reality and an authentic “wrestling” to be done in any written work, but especially in that of Christian fiction. Without the wrestling in a search for redemption or truth, a story will fall far short of its aspirations. McKelvey quotes Flannery O’Connor in pointing out, “The Christian writer does not decide what would be good for the world and proceed to deliver it. Like a very doubtful Jacob, he confronts what stands in his path and wonders if he will come out of the struggle at all.”

Certainly there are lighter Christian fiction stories, and darker Christian fiction stories. These will attract audiences based on preferences. But each of these stories, lighter or darker, should include some struggle that is authentic to life. It is in these struggles that the real power of story shines as more than mere escapism or triteness. Perfect or imperfect resolution aside, the struggle is the story’s heart and soul.

Advertisements Share this:One does not see God in the whirlwind without confronting the whirlwind. (McKelvey)