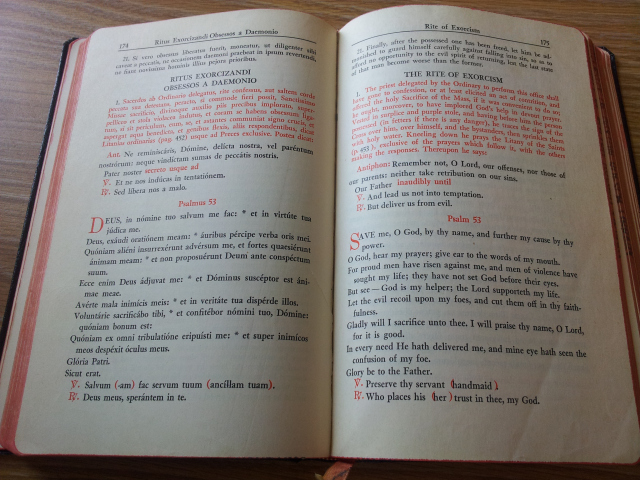

I’ve long said that “every formula of exorcism contains a conjuration.” In fact I once went so far as to demonstrate the Exorcismus in Satanam (also called the “Leo XIII Exorcism”) could be used as a conjuration formula with just a slight change in wording. I did this just to prove a point.

Turns out I’m not the only one who sees this. This morning I read a blog post from Dr. Francis Young describing this phenomenon in more detail.

I’ve yet to read Dr. Young’s book, so my comments will be limited to what he says in his article. In the article he mentions exorcism’s “intimate relationship with ritual magic” and draws parallels between exorcism formulae in the medieval liturgical books and conjurations as found in the grimoires, citing CLM 849 (the “Munich Manuscript”) as a particularly egregious example. So far so good, as these are things I’ve talked about previously.

Then he says this:

Exorcism can with some justification be described as the foremost ‘Christian’ element within western magic, along with the ‘Arabic’ tradition of astral magic and the ‘Jewish’ tradition of Solomonic spirit conjuration. However, whereas the textual traditions of astral and Solomonic magic have been extensively studied by scholars of magic from the nineteenth century onwards, the textual tradition of exorcism has been neglected. The interconnections between official liturgies of exorcism and unofficial magical practices have consequently been missed.

I’m glad he said this and can’t believe this is something that slipped past my radar. I knew of the Arabic “astral/planetary” tradition and the Hebrew tradition about golems and vessels of brass, but it never occurred to me that exorcism was the explicitly Christian element. Perhaps this is because I was too close to the subject and still see exorcism as merely the flip side of conjuration.

After seeing exorcism and conjuration as two sides of a coin, the similarities between exorcism rites and the grimoires became (for me) a case of assumption: the magicians drew from Christian rites because they themselves were Christians living and breathing in a Christian culture. This includes the so-called Keys of Solomon with its Exorcism of Water lifted nearly verbatim from the Catholic rite for making holy water and its use of the Pentagrammaton on the Second Pentacle of Mars.

The name “Yeheshuah” is spelled vertically in the center.

Okay, we’ve just seen that making assumptions can blind us to other data, and I’d like to follow this up by doing more reading on exorcism as the distinctively Christian contribution to the melting pot of Ceremonial Magic as practiced before the Lodge era. Expect me to blog about this again in the future.

This brings me to another thing that Dr. Young’s post brings home: the problem with the post-Vatican II rite of exorcism (De Exorcismis et Supplicationibus Quibusdam, 1999). If you’ve been following this blog for awhile, you’ll recognize it as The Vatican II Rite of Exorcism that I translated and the Vatican DMCA’ed last February.

When I first laid eyes on the new rite back in 2005, my first impression was “Do they actually expect this shit to work?” Now, you’ve got to understand that most exorcists don’t do it “by the book” anyway; the nature of exorcism – that is, conflict and confrontation – makes it something that defies scripting. Even so I found the new ritual’s text lacking, especially in its main thrust of actively avoiding confrontation or even direct address to the entity. While “imperative formulae” which do address the entity are found in the book (nn. 62, 82, 84), they’re all strictly optional.

Not only that, but the new rite makes no attempt to bind the spirit (the Praecipio Tibi from the pre-Vatican II ritual) and attempts to bring the bystanders into the rite by cueing them to say the Creed, the Litany, or the Lord’s Prayer along with the exorcist. From a practical standpoint I’d advise against this because by including the bystanders in any of the exorcist’s prayers, the rite unwittingly draws them into the exorcist’s arena with a spirit who’s not been bound. This is why the pre-Vatican II rite first binds the spirit and then puts the bystanders off to the side praying the Our Father and Hail Mary over and over again: it’s a conscious precaution to keep them out of the arena and as far out of harm’s way as possible.

I’m not alone on these conclusions, either. In a 2000 interview with 30 Days, the Vatican’s foremost exorcist (Fr. Gabriele Amorth) tells us: “This long-awaited Ritual has turned into a farce. An incredible obstacle that is likely to prevent us acting against the demon.”

In the same interview he also says the new ritual was not put together by specialists, that exorcists were not consulted during the ritual’s drafting, that suggestions from exorcists were “unfavorably received,” and that “none of the members of these commissions had ever performed an exorcism, had ever been present at an exorcism and ever possessed the slightest idea of what an exorcism is.”

If Fr. Amorth gives us the icing, it’s Dr. Daniel Van Slyke who gives us the cake in his The Ancestry and Theology of the Rite of Major Exorcism. This paper is meticulously researched and I recommend it to anyone with a more-than-superficial interest in Catholic exorcism. After giving a run-down of how both rites are structured, Dr. Van Slyke observes that “a priest may conduct the entire major exorcism of [Exorcism ritual] 1999, in complete obedience to its rubrics, without once directly addressing the demon. This is a radical break from the rite of [Rituale Romanum] 1953, wherein not one of the many lines addressed to the demon was optional.” (emphasis mine)

The entire paper is a fascinating read, but where Dr. Van Slyke really hits home is his description of how the 1999 ritual came into being. He tells us the ritual was drafted by “Study Group 23,” which was responsible for revising the texts of the sacramentals (blessings, exorcisms, etc.). One of the directives for Group 23 was to “remove all superstitious elements” from the sacramentals, which could be interpreted to include apotropaic elements (i.e. those directly countering evil).

Dr. Van Slyke documents this directive in footnote #69. It loosely translates that “in blessings the element of invocation against diabolic powers may be admitted: however it must be guarded against that the blessings do not become like ‘amulets’ or ‘talismans.’”

The paper goes on to discuss theologians who likely influenced Study Group 23, the notion of “epiclectic” exorcism, and concludes by saying:

“In short, careful theological, historical, and literary analyses demonstrate that the rite of major exorcism was not, in accordance with the mandate of the Second Vatican Council, ‘revised carefully in the light of sound tradition.’ Rather, the rite of major exorcism was rewritten in order to accommodate experimental and tendentious opinions on possession and exorcism.”

This brings us back to our discussion on exorcism and its relation to ritual magic. It’s not a relationship the Church didn’t know about, as in 1948 Fr. Philip Weller discussed magical elements as being present in medieval exorcism rituals (The Roman Ritual, Volume II, in his preface to the rituals of exorcism), and I’ve previously mentioned the parody exorcism Omne Genus Demoniorum found in the Carmina Burana, which pokes fun at exorcism while relaying actual formulae found in Codex Uppsaliensis C 222 (the actual formulae are transcribed and discussed by Rudolf Simek in Myths, Legends, and Heroes: Essays on Old Norse and Old English Literature).

My point is that between Weller’s mention of it, perusing samples of medieval rituals, and Group 23’s directive against anything apotropaic, I’d reason both that the magical connection with exorcism has always been there, and the Church has always been aware of it.

While it would seem we’ve strayed far from discussing Dr. Young’s paper, I think such a detour was important. It’s important because not only is the relationship between magic and exorcism intimate and ever-present, but that it’s essential for getting the job done. While Dr. Young hits every nail on the head when discussing this relationship and the popularity of exorcism formulae amongst magicians, I’d say there’s a flip side of the coin that matters just as much: the magical content of the Church’s exorcism rites – the grounding on what can be called “sound magical principles” – are what makes them useful, whether by “useful” we mean spiritually or on a strictly psychological level.

Advertisements Share this:

![faking it cd[3]](/ai/058/426/58426.jpg)