It was a typical day at university for Professor Stanley Fish. He had just finished teaching his linguistics class. Some of the names of linguists he had discussing with his students were still on the board when his next class started to arrive for their literature seminar. Fish decided to make one small change between classes. He drew a box round the assignment details and wrote p43 at the top.

It was a typical day at university for Professor Stanley Fish. He had just finished teaching his linguistics class. Some of the names of linguists he had discussing with his students were still on the board when his next class started to arrive for their literature seminar. Fish decided to make one small change between classes. He drew a box round the assignment details and wrote p43 at the top.

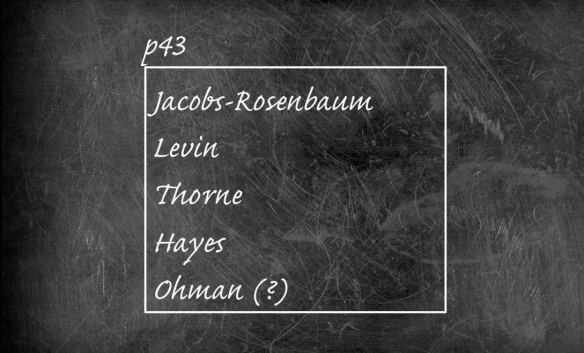

The list now looked something like this:

Fish’s next move was simple but significant. He told his literature students that there was a religious poem on the board, similar to the ones they had been studying the past few weeks, and he then invited them to interpret its meaning. The students duly obliged and it wasn’t long before they were offering all kinds of interpretations, from initial readings of the poem as a hieroglyph to highly convincing interpretations of the symbolism of the Hebrew names Jacob, Rosenbaum, and Levin.

What Stanley Fish had stumbled on, and what he found on every occasion he repeated the trick, was the reality of how readers tackle the act of interpretation. His little teaching sleight of hand had revealed that readers do not approach literary works as isolated individuals but rather as part of a community of readers. As he writes in Is There a Text in the Class?, ‘it is interpretive communities, rather than either the text or reader, that produce meanings.’

In essence, Fish’s literature students did what literature students do in a classroom situation: they interpret the text put in front of them by looking for allusions and patterns of meaning, regardless of whether they are even there. The more the students interpreted specific parts of the poem, the more they convinced themselves that they had built a coherent sense of its overall meaning. The only problem, of course, was that it was all nonsense. There was no poem and therefore no meaning!

At no point did any of Fish’s students question the validity of the text itself, or whether what they were interpreting was even a poem. Because they were working in the context of a literature class, in the presence of a professor of literature and confronted with what looked like a poem, they assumed it was a poem and without thinking they adopted the rules for interpreting obscure religious verse they had learned – rules they had clearly internalised from years of making inferences about literary texts.

Now, we could lament the way that a bunch of hitherto bright students could be so uncritical in their approach to reading. We could even despair at how cultural relativism has reached such a nadir that a simple list of linguists could be mistaken for a profound religious poem. I think, however, this misses the point. As Fish notes, this is ultimately how we approach reading all texts, literary or not – as a community. Even to interpret a list of linguists as a list requires a shared understanding of the concepts of seriality, hierarchy and subordination. This is the nature of interpreting meaning from text.

I think there are some lessons to draw from Fish’s work in relation to teaching and, more specifically, to curriculum design. The first is to recognise the responsibility we have in selecting the texts we teach. We should make sure that what students will be interpreting has substance, both in terms of its intrinsic value and its utility. Mark Roberts has written about the failure of poems like ‘Tissue’ to do either of these things well. I’ve never taught ‘Tissue’, but as long as I can remember there has always been quite a bit of guff like that in the GCSE anthology, most of it sadly of the contemporary variety.

Don’t get me wrong, I am not against modern verse per se, and I am certainly not suggesting we should avoid all forms of contemporary literature. That said, I don’t think GCSE students should be wasting their time interpreting poems like ‘Tissue’. The funny thing is that most of the students I have taught seem to share a similar view. I always think classes will respond much better to poems like ‘Brendon Gallacher’, ‘Blessing’ and ‘Kid’ but actually when they write about ‘My Last Duchess’ or a Shakespeare sonnet they have much more to say and they say it with much greater conviction.

The second important lesson we can we learn from Stanley Fish’s work on interpretative communities relates to the order in which we teach students the poems that we select. I’m guessing that one of the main reasons that Fish’s students so readily interpreted a list of linguists as a religious poem was because they were used to seeing poems that looked like that, namely without a clear form or discernible structure – they understood the free verse style that characterises much of the poetry of the last century, and which has dominated the contents of many an anthology since.

Whilst Fish’s students may have mistakenly treated his list of names as a poem, they would have probably have understood why a poem that doesn’t rhyme or contain any clear poetic structure could be considered a poem. They would be familiar with poets who broke with formal conventions, like e.e. cummings, Sylvia Plath and William Carlos Williams, and learnt the reasons for these literary developments. In short, they would have in mind some kind of literary chronology, which is perhaps something that we should bear in mind when we are designing the spread of a five-year curriculum.

Perhaps most importantly, I think Fish’s example highlights a need for us to consider how we approach teaching poetry, particularly in a clear and systematic way that builds upon the work of KS2 teachers. I wonder if one of the reasons why Fish’s students were misled by a mere list, is that they had never really been encouraged to take a step back whenever they approach a new text – to appreciate its overall beauty; to consider it at a conceptual or formal level before diving straight in to try and account for it and locate its meaning. Maybe whenever they were ever presented with a poem at school, they were immediately asked to interpret or provide some kind of emotional response.

This is all well and good, and I do this kind of thing regularly. This year, however, I have been teaching a year 7 class for the first time in ages, which has given me the opportunity to begin to think through how I might teach things like poetry a little differently, by which I mean to teach students a conceptual appreciation of poetry as well as an emotional and technical understanding. I want them to be able to infer meaning, but also to comment on different forms and how these might be linked to developments in artistic expression and philosophy. A more holistic approach to understanding.

This is obviously hard. It is so tempting to introduce a poem and start to elicit ideas about its meaning, but this might be putting the cart before the horse, particularly with poems where the structural and/or formal features are absolutely central to understanding what the poem is trying to achieve. I wonder that whilst many of us are reviewing our KS3 assessments, we should recognise that here we have a unique opportunity to influence the workings of literary interpretation from within that interpretative community. There are enough of us and we have sufficient time to significantly improve they way we teach our students to read and approach poetry, or indeed any text for that matter.

Who knows, if we got things right from the off, by the time they were in year 11, our students might even be able to understand the difference between a metaphor and a simile.

Anyway,

thanks

very much

for

reading….

Advertisements Share this: