In a time of dramatic social upheaval and tension-filled civil rights movements, a group of women quietly organized to fight for their right to work. And despite their historic efforts, the fight continues.

women quietly organized to fight for their right to work. And despite their historic efforts, the fight continues.

The Good Girls Revolt: How the Women of Newsweek Sued their Bosses and Changed the Workplace by Lynn Povich is an account of how 46 women working at Newsweek realized the systematic discrimination being committed against them in their workplace, and how they rose to the challenge of speaking out. Povich details the story of women who, despite having better credentials and better talent, were constantly denied promotions and opportunities to write at Newsweek in favor of men to fill the paper’s bylines.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, women were struggling between the increasingly archaic yet long-held belief that a woman’s place was in homemaking and not in having a career. In a post Feminine Mystique society, women were gradually prodding at careers they were passionate for and longed hold their own with the men who had dominated their fields for years. Yet, they were consistently held back by both male bosses and societal conventions. This book is an account of how 46 brave women chose to take a stand, despite what that might mean for their jobs, marriages and lives, as well as what the pervading culture might think of them.

Povich weaves the sexism and sexual promiscuity of a Mad-Men, newsroom culture with the collective awakening of feminist thought in a wonderful way that really shows how these women realized their worth and value — and the crimes being committed against them. This was a fascinating account, especially from Povich’s point of view, as she was one of the key players in the complaint and was forced to deal with the outcomes of their fight in many ways.

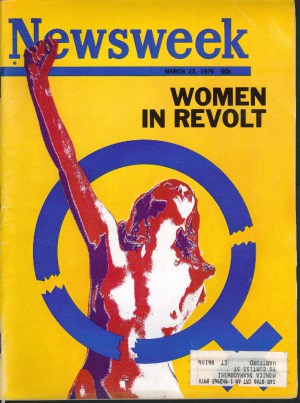

Due to the rising feminist movement in America, Newsweek decided to run a story titled “Women in Revolt,” and despite the abundance of willing and able women already on staff, the newspaper brought in a contracted woman writer to write the story — a trend that would continue later. The same day the cover story hit the stands, the women, along with their fiery, passionate attorney, held a press conference stating they had filed a complaint with Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in an effort to charge their employers with discrimination against them in hiring and promotion opportunities.

While the complaint got the attention of their employers, the Newsweek women were still facing discrimination and efforts to keep them from advancing — writing tryouts and inquiries about byline opportunities were continually fielded by editors who either disagreed or didn’t care about giving them what they rightly deserved. After a year of half-hearted change, the women again confronted their employers and eventually saw some change. Women who had worked for Newsweek for years were promoted to writing and correspondent positions, with Povich even reaching the esteemed level of Senior Editor, becoming the first woman to do so in the history of the magazine.

Yet, with all this hard work, the book begins with an introduction to two young journalists who are facing the same problems in the 21st century, where men with less experience and less talent are promoted over them.

This makes me angry.

As a journalist myself, I know that the industry is leaning heavily toward a female majority, which is a major coup in feminist history. From my experience, male writers are given no more priority over female writers when it comes to byline — it simply comes down to talent. However, I have no doubt that this is still a common occurrence at major, national publications that still function as good ol’ boys clubs. How can this be? It is simple: a lack of willingness to change when you are benefitting from the discrimination.

However, on a smaller scale, the efforts of these women is deeply felt: All of my editors have been female and I currently work at a magazine where all of the immediate leadership is female. I wonder if this would give some of those women some satisfaction in knowing that their fight meant something. There is a wonderful quote from the book that I think accurately describes the situation then and now: “The women who fought those fights were not the ones who got the rewards. People like me, who came right behind them, got the good jobs and promotions…” This reality is very well-illustrated in Povich’s book. And one can only hope that they know how much people like me appreciate what they did for my future, even before I was born.

As far as Povich’s writing of the story, I felt it was sub-par. She included all the facts of what happened, as well as quotes from women who participated in the complaint and her former editors and bosses. And there were times when I could feel the desperation for change in her words. But mostly, the book was flat, disorganized and disconnected. This is an important story to tell, and especially crucial for female journalists to know, but I believe it could have been told in a much, much better, more immersive and more emotional way than it was. I recommend reading it solely for the story, if you can muster the energy to ignore the disparate technicalities of Povich’s writing.

—

What did you think of Lynn Povich’s The Good Girls Revolt? Do you think their efforts to change the workplace for women had an effect then and now? What kind of precedent does this set for women in workplaces other than newsrooms? How can we continue the fight for equal workplace treatment for women? Let’s talk.

Advertisements Share this: