© Magnus Forsberg

© Magnus Forsberg

★★★★½

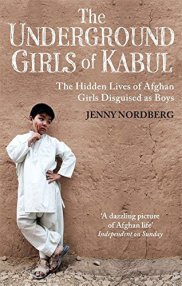

The Hidden Lives of Afghan Girls Disguised as Boys

Necessity is the mother of invention. That’s the message of this astonishing work by the Swedish journalist Jenny Nordberg, who worked with women in and around Kabul in Afghanistan between 2009 and 2011. When she was told, discreetly, that a contact’s six-year-old son was actually a cross-dressed girl, Nordberg discovered that this was merely the tip of an iceberg. Her enquiries led her to unearth an open secret in Afghan society: an entire social practice, hitherto unreported in the wider world, of bacha posh, literally meaning ‘dressed as a boy’. Mixing biography, psychology and anthropology, this is a deeply illuminating journey into the social constructs of an unfamiliar world.

One of the women whom Nordberg meets – whose sister is a bacha posh – is very frank when asked why a girl might agree to be raised as a boy. Her answer is blunt: ‘Do you understand that it is the wish of every Afghan woman to have been born a man? To be free?‘ For freedom, even in its most minor form, is never a given for an Afghan woman. As a young girl, she must be kept pure ready for marriage. Her virginity is her only capital and the bride-price she commands is dictated by her reputation in her local community. Is she modest? Decorous? Respectful? Does she keep her eyes lowered? Does she cover herself properly? Once married, her value (and the honour of her husband’s family) depends upon her ability to give birth to sons. Sons are the visible sign of status and longevity: more than that, in an unstable political climate, sons are a sign of a family’s strength. And so a family composed only of daughters is a tragic humiliation.

Even if the new parents are relatively liberal, their community is likely to judge them on their lack of male children. The father may also be mocked as being weak if his wife produces only girls. And so, sometimes, parents take the matter into their own hands. In a practice that appears to be ancient, though recorded only by hearsay, and then only to trusted friends, a girl-child may be raised as a boy from a very early age until the onset of puberty. During that time, she is treated by her family and by her community as a boy, with all the privileges that implies. She can help her father in his shop, or run errands, or play football, or go out alone, or accompany her mother and sisters as a male guardian. But Nordberg begins to wonder about the effects of such a lifestyle. When such a girl reaches puberty, what does it feel like to be suddenly stripped of all the privileges she has come to take for granted as a boy? What are the psychological effects of the change? And are there consequences if a bacha posh remains a boy for too long?

Nordberg’s quest takes her deeper into a network of rumours, recommendations and hints that lead her to a series of remarkable women. Some are the mothers of current bacha posh. Some were bacha posh in their own childhoods and have used the education and confidence that came with honorary-boy status to carve out stronger roles for themselves as women. Sometimes these roles bring them success; sometimes, ultimately, their strength becomes a handicap. Some are bacha posh who sail dangerously close to the wind, stubbornly maintaining their male identity even after the onset of menstruation and resisting the socially-acceptable transformation back into femininity. And others are bacha posh who never stopped: who have, through determination or good fortune, managed to construct lives in which they continue to live as men, usually supporting elderly or infirm family members in the absence of ‘real’ sons.

These women all speak with extraordinary candour about their experiences, as Nordberg delicately teases out the details of their story. Her knowledge of the region’s culture leads to some fascinating excursuses: similar practices in other countries; examples of Western women who lived as men; the possible impact of Zoroastrianism on the development of the bacha posh practice; the lack of opportunity for female sexual expression of any kind in Afghanistan; the fact that, bizarrely, in long-term bacha posh, the body itself seems to confirm to the mind’s adopted gender… These matters are all intriguing. And the story is all the more urgent because it takes place in such a febrile country, where Nordberg’s interlocutors find their lives changing from one year to the next, and war is never far away. It is also a sobering tale, because one can’t escape the feeling that the situation is far better at the start of Nordberg’s journey than towards the end. As well as a picture of gender roles, it’s an implicit criticism of the grand notions of Western state-building and foreign aid initiatives, which are often calculated to satisfy investors back home rather than the actual needs of communities on the ground.

Norberg is an excellent guide to a shadowy and complex subject, and she reports many of her conversations verbatim, allowing her contacts to speak for themselves. Thorough and conscientious, it’s also a terrifically good read and leaves you burning with frustration on behalf of these smart young women, who find their worlds circumscribed before they even have a chance to get to know them. It’s a meaty and powerful book. Do seek it out if you fancy broadening your horizons and your mind.

Buy the book

Share this: