¡Buenos días!

¡Buenos días!

November is Native American Heritage Month. Typically, this means that the internet is flooded with underwhelming and endless lists of books highlighting “Indians and Pilgrims” – using this as the only opportunity throughout the year to discuss indigenous peoples of the US, and typically through a distorted lens.

We’re taking a different route, one that will celebrate the lesser-told stories of individual cultures and stories among Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

A brief aside: There are amazing educators out there who are debunking, challenging, and critiquing how to teach Native American Heritage Month in the classroom. A few of them offer resources that we wanted to put at your fingertips: Check Your Curriculum? Are Native Americans in the Past Tense? by Zinn Education Project; Some Thoughts About Native American Month and Thanksgiving by Debbie Reese of the American Indians in Children’s Literature blog; and the Rethinking Columbus guide from Rethinking Schools. These are just a few. As you find others, please add them to the comments below.

Since we at Vamos a Leer have been engaging in this conversation every November for the past few years, we’ve compiled other resources that may be useful to you. You might consider checking out our content on teaching about Indigenous Peoples, as well as our related materials on Rethinking Thanksgiving. And finally, you might refer, too, Reading Roundup of “10 Books About Indigenous Peoples of Latin America” – some of which we’ll cover in more depth in this month’s reviews.

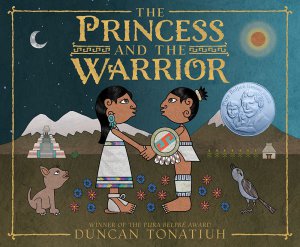

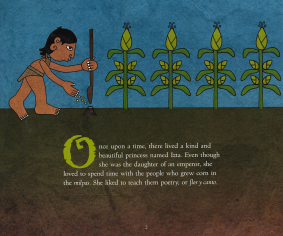

We begin our reviews this month with the children’s book, The Princess and the Warrior, written and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. This title is an Illustrator Honor Book of the 2017 Pura Belpré Award and a Commended Title for the 2017 Américas Award, among others.

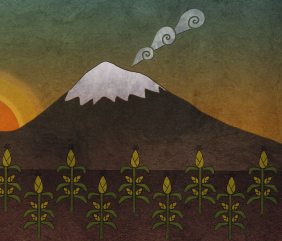

In this book, Tonatiuh tells his own version of the legend of Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl, which are the two volcanoes southeast of Mexico City. Tonatiuh recounts the legend of how these volcanoes came to be, but adds his own twist to this well-known Mexican story.

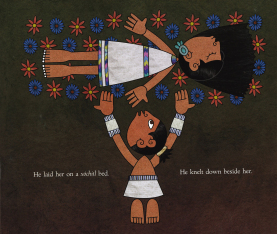

The book is a love story about the beautiful princes Itza, who falls in love with a warrior, Popoca. Itza’s father, the emperor, prefers that Itza marry a powerful tlatoani, or ruler, rather than a simple soldier. However, he concedes that if Popoca is able to defeat Jaguar Claw of the neighboring area, with whom they have been at war, Itza and Popoca can marry. Although Popoca fights bravely and eventually triumphs over Jaguar Claw, a twist in the plot leads Itza to believe that Popoca has actually been defeated. In her grief, Itza drinks a special octli (fermented beverage) and cannot be awoken. Popoca, grief stricken, lays her on a bed of flowers and remains by her side throughout time. And that is how the two volcanoes came to be. As Kirkus Reviews writes, it’s a story “equal parts melancholic and transcendent – a genuine triumph.”

Tonatiuh tells the story beautifully, weaving Nahuatl words and appropriate cultural references seamlessly throughout. Nahuatl is the Native language spoken throughout central Mexico since before the Spanish arrival in the 1500s. It also refers to the ethnicity of people whose families have spoken the language for centuries. Although Spanish is still the most widely spoken language in Mexico, about 1.7 million people speak Nahuatl today. This book would be a great opportunity to teach about the history Nahuatl people across central Mexico; it touches on its governmental structure, in addition to traditions related to agriculture, food, poetry and war.  The Nahuatl words used in the book are italicized and explained in Tonatiuh’s glossary at the end of the book. The glossary not only defines the words, but it also describes their cultural significance. Their inclusion allows for the opportunity to discuss indigenous languages.

The Nahuatl words used in the book are italicized and explained in Tonatiuh’s glossary at the end of the book. The glossary not only defines the words, but it also describes their cultural significance. Their inclusion allows for the opportunity to discuss indigenous languages.

In the Author’s Note, Tonatiuh contextualizes his story within Mexican history and explains the different versions of the legend. It is obvious that he has done his homework, as he is very knowledgeable about the legend’s different versions. The bibliography that Tonatiuh includes further demonstrates his knowledge of legends and pre-Spanish Mexico.

Even the illustrations of the book are meaningful for sharing and documenting culture. As Tonatiuh goes on to explain in the Author’s Note:

Even the illustrations of the book are meaningful for sharing and documenting culture. As Tonatiuh goes on to explain in the Author’s Note:

“My illustrations draw from the images in those Mixtec codices, and I wanted to pay tribute to them. Readers may notice how in my drawings, as in the ones from those codices, people and animals are always drawn in profile. Their entire bodies are usually shown, and their ears often look like the number 3. Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl have inspired artists for hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of years. Storytellers, poets, painters, photographers, and others have created pieces of art to honor the magnificent mountains. My hope is that my story contributes to this vast tradition of art, and that it introduces the volcanoes and their legend to a new generation of young readers.”

Katrina’s educator’s guide to Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote, another of Tonatiuh’s books, provides resources for educators who want to learn more about his artwork and includes ideas for how to bring Mesoamerican art into the classroom. The same guide also has resources on storytelling and fables, which might be another means of sharing this book with your students.

In sum, this book would be a great addition to your classroom and home bookshelves. Here are some resources to accompany it in the classroom:

- In regards to learning and teaching more about Nahuatl:

- Here is a general introduction to the Nahuatl language

- From Remezcla, an article on apps that “Teach the Culture and Languages of Mexican Indigenous Communities” (including Nahuatl).

- From NPR, a piece on how, “Far From Mexico, Students Try Saving Aztec Language.”

- To hear the language spoken, here is a beautiful short animation of the poem, “Cuando muere una lengua” (When a Tongue Dies), recited in Nahuatl by Miguel León Portilla. The animation has Spanish subtitles, The Vimeo link includes the Spanish, English, and Nahuatl written poem to accompany the oral recording.

- And on the note of endangered indigenous languages, the same producers of the video above have also produced several other shorts documenting other languages of Mexico, including but not limited to: 68 voces: Purépecha; Tsotsil. La Reunión de los Espantagentes; Tojolabal. The Tiger and the Grasshopper. Yaqui/Totonaca de Puebla. Muere Mi Rostro.

- For those who want to know more about Tonatiuh’s process of writing this book and others:

- The book trailer

- Tonatiuh shares his thoughts on The Princess and the Warrior as a guest blogger on the TeachingBooks.net blog.

- In April of this year, my fellow blogger, Hania, interviewed Tonatiuh about his work. In the interview, he talks about The Princess and the Warrior.

Saludos,

Kalyn

Images modified from: The Princess and the Warrior

Share this: