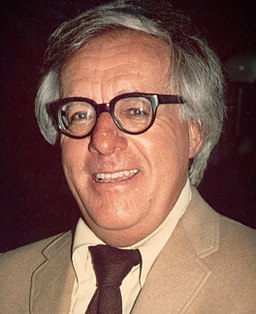

“Write a short story every week. It’s not possible to write 52 bad short stories in a row.” — Ray Bradbury

From Wikipedia

This year, inspired in a large part by my old friend and bandmate Ian who embarked on 100 straight days of drawing last year (viewable here), I have decided to attempt the “Ray Bradbury Challenge,” as described above. Every Sunday in 2018 I will post a new, short work of fiction. This is a new hat for me, being primarily a nonfiction writer and essayist. But if you don’t try new things, you don’t grow. In the past month of sailing, writing, and playing music, I’ve built up some good creative momentum; I’m going to try and keep it going.

I can’t promise my short stories will be very good (in fact, I might even prove old Ray wrong with a year-long string of flops, uninterrupted by anything remotely redeeming), but I can promise that I’m going to learn something from this, something which I hope will carry over into my nonfiction work and make me a better writer because of it. So come along with me, if you like, on this journey of discovery. Enjoy them – I’ll certainly try to. Take from them what you like, and leave the rest. Most importantly, please read them with an open (a very, very open) mind. Remember- I don’t know what I’m doing, either, but maybe by grasping around in the dark I’ll stumble across something that’s worth both of our time, as writer and reader. I guess that’s all any writer can hope to do.

So now, without any further hullabaloo or delay, here’s the first one. See you next week.

HALF-SPENT WAS THE NIGHT

by John Wolfe

To the west, the sky blended from red to orange to yellow, bright bands of color creasing the horizon against the oncoming darkness. The light had faded too quickly for Lucy’s liking. Soon, she wouldn’t be able to see the mountain, and then she would either have to stop and camp for the night, or follow the narrow beam of her headlamp on the forest floor – so long as she could still see the mountain. Her GPS had expired at lunchtime, and her compass, dumbly, was in Evan’s bag (she had told them one compass for four people had been a silly idea) but still, she wasn’t worried. She had her bearings. The mountain was right there in front of her; so long as she could see it against the stars, she would be fine. But night was coming.

East-southeast, she repeated to herself. That was the way she had to head to make the mountain by dawn. Not that it meant anything without a compass. Somewhere she had read something about moss only growing on the northern side of trees, but she had trouble imagining herself knelt over, patting the bases of the trunks in the dark. She had paused for an evening meal by a stream – cold tuna, straight from the can, with crackers – so she could walk until morning without stopping to eat. But it would be foolish to walk in the wrong direction. She might miss the mountain entirely. East-southeast, she thought. Easy enough. Keep going, girl – they’ll be expecting you by lunch.

When she took this side detour, she told them it would only take her two days. Twenty miles on the map from the trailhead to the painted caves to the mountain they would meet at. They were probably there already. She imagined them now, sitting on logs with a fire going and Evan playing his little guitar and James caterwauling along and Julia, knowing an army marches on its stomach, stirring a pot of jambalaya (wonderful cook that she was, she had dehydrated the andouille before they left) over the campfire. Lucy could almost smell the spices. But no- they had wanted to stay on the trail, leaving Lucy alone to explore the painted caves.

It was better that way, Lucy thought. She could explore at her own pace, which she greatly preferred. She could never stand to go to museums with people for the same reason. The world was most wonderful to her when it was hers alone to discover. Her mother told Lucy she had always made her own path, anyways, even as a toddler, ignoring her older brother Michael, who had always tried to show her the way. But she missed the company of her friends, and knew they would have enjoyed the caves. No matter. She would see them tomorrow morning, and tell them about her side sojourn then.

An hour into her lonely night march the moon rose, a waxing gibbous, hazy on the horizon. By its light she could see the peak in the distance which she was making for. Good, Lucy thought. She was going the right way, and it wasn’t too much further. She quite enjoyed the night walk, alone though she was. There was enough light from the moon through the trees to cast patterned shadows on the forest floor, allowing her to pick the best path through the underbrush in the direction she wanted to go. The crickets chirping quietly around her made for a calming symphony of white noise, a pleasant thrum in the background of her thoughts. She paused to pull a sweater from her backpack, donned it against the nighttime chill, and kept going, switching her headlamp off to let her eyes adjust to the darkness.

Momentum is an important thing in any endeavor, and with hiking this is especially true. Lucy knew that to keep up the rhythm of her steps was the most important thing, but she had been walking all day already (not to mention climbing and crawling through the caves) and with the coming of darkness her circadian instincts got louder and she found herself slowing in stride, her eyelids drooping. Perhaps she should stop to make camp. But no- no- she saw the mountain in the distance, and she still had a little energy left. A granola bar helped stave off fatigue for a few moments as she chewed. She sang songs to herself to help keep awake: some Beatles songs (it was all Evan knew on the guitar) from Sgt. Peppers, and for some reason, Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming, even though Christmas wasn’t for another few months.

She had always liked that song, how it seemed to hauntingly catch some fragment of beauty few other songs came close to even recognizing. It was in a major key, but the moments that switched to minor chords added something else that she couldn’t put her finger on. It was like by adding little snips of sadness, the happy moments were made happier. She had sang it first in the youth choir, before she stopped attending the church her family went to. The whole family had stopped going after Michael’s accident, except her father, who still to this day attended with a kind of dogged determination, as if his faithful attendance could somehow change the past. Her mother, however, had stopped leaving the house almost entirely for months afterwards, except to go straight to the hospital where Michael was, and straight back home, never even stopping at the grocery store or anything. Lucy had gone to visit Michael, of course, but after a while she couldn’t bear to see Michael in that state and ended up staying home with Mom. She was still living at home, then, but Michael had been in college. He had rolled his Jeep in a moment of drunken indiscretion with his fraternity friends and went from the bright-eyed boy she knew, her buddy with whom she explored the creek in her backyard with as kids (she did occasionally let him lead her around) and who basically tutored her through all the math classes she took in high school and who had transformed, in eight impossible rolls and a sudden stop against the guard rail, into a sallow figure, thin on his hospital bed, his brain bruised and broken, a shell of himself. Two of the passengers had died, but Michael and the driver, who were both on the same side of the Jeep, had lived.

And she had lived too, despite the pain at first, and although Mom was never the same (Dad wasn’t really, either, although he was better at hiding it) afterwards they had eventually readjusted to their daily routines the best that they could. But there were, and there always would be, a scar in their lives. That’s the reason Lucy was out here, hiking through the woods in the darkness. The motion of walking was a kind of salve; when she moved, it didn’t seem to hurt as bad, somehow. Now she walked for both of them. And after all it was Michael who had first told her about the painted caves. He had gone there with some girl back when he was in high school, and wouldn’t shut up about how beautiful they were (or what he and the girl had done there) for weeks afterwards. She had always wanted to go there with the whole family, but there was never time, and now there never would be.

She had seen what he had meant, though. Those caves were spectacular- they seemed to go on forever into the earth, and after she was past where the light shone through from the narrow entrance, the cave walls took on a new glow from the brave light of her headlamp, the red rock transforming into something beyond what she had thought red could be capable of, at least on this planet. It was like a color from Mars, or some other distant world. Maybe it had gone through some wormhole, from someplace far away in space and time, and refracted back to this ashen-colored planet, bringing a light not possible from this sun. It was faint, maybe from the distance it had traveled, but it was still more vibrant than anything else she had seen before. Michael told her it was all the quartz dissolved in the clay which caused the light to refract in that way. Only in this one spot in the whole state, he had said, was there enough concentrated quartz to cause the effect.

Light- light! That was what had gone! For the past- shit! how long had she been walking this way? Clouds had rolled over and covered up the moon, and the light no longer illuminated her steps through the dark forest. She had gotten lost in thought, thinking about the caves, and Michael, and times before, and now she was lost in real life. There were no stars, no mountaintop on the horizon in front of her. She clicked on her headlamp, blinded for a moment by the whiteness. Her world shrunk to a few tree-trunks around her, their barked backs reaching up into blackness. There was no moss on any of them. Her heart beat faster in her chest as she realized she no longer knew where she was. Calm down, she told herself, relax. But the world outside her little headlamp’s glow loomed deep. There was no telling what was out there. The crickets had stopped, and strange noises now came from the woods. Cracking branches, the skeletal whispering of trees in the wind. She imagined she heard a low growl, but she pinched herself- snap out of it, she thought. You’re letting your mind get the best of you. You’ve been in the woods at night before- it’s a whole lot of nothing. But she couldn’t say for sure, though, what was out there.

No light filtered through the heavy clouds. There would be no more walking tonight, but to stay here wasn’t appealing, either. She set up her tent under a nearby tree, hoping it’s thin fabric would get thicker, somehow, and block the noises of the night from reaching her inner cloister. She crawled inside, her sleeping bag damp and greasy (they had been camping three days already before she walked off alone, and there were no showers along the trail). She switched off her headlamp and shut her eyes to the darkness, now total around her, and tried to reign in her racing mind.

Lo, how a rose e’er blooming… The words left her lips and entered the night. For a moment, everything was still. It came a flower bright, amid the cold of winter... A lonely cricket began to chirp in the distance. When half-spent was the night…

While she slept she dreamt that Michael could walk again- that he was just as strong as he had been when they were children. Now that she knew what his fantastical caves looked like, her dream took on a reality of setting, and soon in her sleeping mind they were exploring together as a family, as they had always wanted to, their parents holding hands together. Mom was looking happy for the first time in ages, Dad’s hair the healthy brown it was before the accident, instead of a fussed gray, and his beard was back, too. Together they strode into the darkness, and when Michael switched on his headlamp, all of their faces all took on the same rosy glow in the quartz-reflected light.

And then all of a sudden the sun was up again. When she unzipped her tent and peered outside, the mountain lay before her, an easy hour’s walk. She could see the tiny remnants of a campfire smoldering on the hillside, and three little tents clustered around it. She could be there in time for breakfast, if she hurried. She packed up her tent and walked, a new rhythm to her steps that had been missing in the dark. Lucy knew where she was going, now, and knew she would be there soon. Dawn’s light peeked over the corner of the mountain, and the soft amber glow of morning touched Lucy’s face, which was now, without her even meaning to, curling into a smile.

Advertisements Because humans are gregarious animals: