***This post is part of the My Favorite Movie Threesome Blogathon, hosted by the Movie Movie Blog Blog. ***

***Some spoilers***

As most of my readers know, I’m a huge fan of classic films and I love to throw my hand in when there’s a blogathon going on. Now, I don’t consider films of the 1980’s classic, at least not for me. I grew up in the 1980’s and saw a lot of these films when they came out in the theaters so I have a hard time filing them away with the classic films of the 1920’s, 30’s, 40’s, and so on.

But when this blogathon came up, I happened to catch the 1989 film Miss Firecracker on TCM and the threesome in the film (Holly Hunter, Mary Steenburgen, and Tim Robbins) hooked me so I wanted to explore the characters and their interaction more closely.

This film comes at the beginning of the rise of the independent film boom of the 1990’s. According to Matt Warren, indie films were on the rise in the 1980’s as a response to the constricting barriers of the commercial film industry at the time:

“[There] existed an electrifying micro-community of independent filmmakers who were creating their art with no clear roadmap to greater riches or acclaim; creators who made work mostly for themselves and a small group of likeminded freaks and weirdoes, who unknowingly established the aesthetic patterns and values that would take root and flourish on a grand scale in the 1990s.” (Warren, par. 4)

These indie films of the late 1980’s and early 1990’s were especially focused on character development, building stories around characters rather than molding characters to fit a bombastic plot, putting characters in the real world rather than a fantasy world of toppling worlds and space ships. Miss Firecracker fits into this mold, putting the viewer in a small Southern town where life moves slow like molasses and loves and hates have time to ferment.

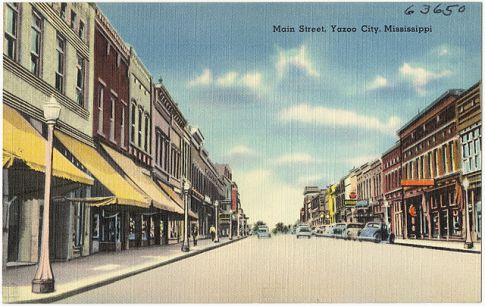

I was a little leery of the premise of this film – Carnelle (Holly Hunter) who has lived in the miniscule Southern town of Yazoo City, Mississippi all her life, decides this is the year she will enter and win the Forth of July beauty contest. It wasn’t the simplicity of this idea that made me wary as much as the fear the film might be about a young woman finding her worth by participating in and winning a beauty contest, which didn’t sit well with my feminist ideals. But, as with many of these indie films, the film is about much more than just what actually happens in the story.

Photo Credit: Postcard of Main Street, Yazoo City, Mississippi. While this postcard is from 1930-1945, judging from shots of Yazoo City’s main street in the film, not much has changed… The Tichnor Brothers Collection, Boston Public Library, Print Department: Monumenteer2014/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 2.0

In fact, my interest in the film wasn’t whether Carnelle would win the contest or not but in watching the relationship unfold between three cousins – Carnelle, her cousin Elain (Mary Steenburgen) and Elain’s brother Delmount (Tim Robbins). Elain and Delmount left Yazoo City for greener pastures years before and return for different reasons. Elain is there to give a speech as a former Forth of July pageant winner, ironically titled “My Life as a Beauty” because, as we find out in the film, her life as a beauty isn’t what it’s cracked up to be. Delount has just been released from a mental institution and comes back to sell his mother’s house so he can head on over to New Orleans to get his college degree in philosophy. But Carnelle pulls them both into the whirlwind of her preparations for the beauty contest, along with Popeye, the woman she has hired to make her costumes (played by Alfre Woodard).

The film is based on a play by Pulitzer prize winner Beth Henley and has a Southern gothic feel to it but, as Roger Ebert points out in his review of the film, “Henley replaces … painful sincerity with a lighthearted goofiness that cheers things up…” (Ebert, par. 2). The film does indeed have a goofy and cheerful tone to it even as the darker shades in the relationships show through.

The strong bond between the cousins begins with Carnelle’s child-like affection and openness that draws the view to her as much as they do Elain and Delmounte. Caryn Jones, in her New York Times review of the film, describes the image of the child Carnelle that opens and closes the film:

“[A] little girl in a fuzzy hat that looks like a cropped yellow wig. She wears a droopy yellow dress, has some missing teeth and smiles excitedly as she waves and blows kisses at someone passing by. She seems so pathetic and so remarkably hopeful that the image is disturbing and resonant, suggesting the poignant funny-looking tale of hope and despair” (James, par. 1)

The lost and loving quality of this little girl carries through in the adult Carnelle but she is not the typical image of the sweet and compliant Southern belle. She has toughed out a difficult childhood, describing at one point to Popeye all the people who have “dropped dead” in her life, including her parents. Her closeness to Elain and Delmount stems from having come to live with her cousins at the age of eight.

In spite of Carnelle’s warmth and vivacious personality, she and Elain have their conflicts, though these seem more on Elain’s side than on Carnelle’s. Their relationship “[creates] a tight little ballet of cousinly ‘love’ and jealousy” (Ebert, par. 5). As we might expect from a former beauty queen, Elain is vain and protective of her status as a beauty that reaches the point of cruelty at times. Much of Carnelle’s fantasy of winning the beauty contest hinges on her wearing the red dress Elain wore when she won the contest seventeen years before. Elain makes excuses until Carnelle is forced to wear an old dress of her aunt’s for the pageant. At the end of the film, Elain’s red dress shows up – folded neatly on the top of all her clothes in her packed suitcase. Elain insists the dress belongs to her, just as the crown she won belongs to her. She is not willing to give someone else a chance at it.

Elain and her brother Delmount’s relationship isn’t all bells and roses either. Delmount, despite his rough exterior, has a sweetness about him and a deep affection for his sister and cousin. Although his motives for coming back to Yazoo City seem selfish, especially since Carnelle has been living in the house he wants to sell, he is far from leaving her out in the cold, promising her part of the money from the sale so she can get away from the small dead Southern town she has lived in all her life. He is a more severe towards his sister, poking fun at her vanity and coaxing her to leave her unhappy marriage. And yet, it’s Elain who rushes to his side when he wakes up from nightmares and with whom he playfully dances in the living room in one of the goofier moments of the film. Underneath the teasing, it’s clear Delmount wants more for Elain than her empty life as a former beauty searching for the adoration she lost. His disappointment is genuine when he finds out Elain has only been pretending to leave her husband and has no intention of ever doing so because he worships her.

Miss Firecracker was not a huge hit, obviously, but it isn’t the monotonous and shallow film that some of the critics make it out to be. James rather harsh critique that “Ms. Henley’s script seems to assume that these eccentrics are automatically funny, and that a brief mention of Carnelle’s orphaned childhood and tawdry past are enough to provide the shape and emotion of a life” (James, par. 2) overlooks the film’s psychological reality does not lie in the actual facts of the characters’ lives but in the deep affections and the subtle hostilities among the three cousins.

Works Cited

Ebert, Roger. “Miss Firecracker”. Rogerebert.com. Ebert Digital, LLC. 28 April 1989. Web. 26 July 2017.

James, Caryn. “Review/Film: Seeking Redemption in a Beauty Pageant”. The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 2017. 28 April 1989. Web. 26 July 2017.

Warren, Matt. “#FlashbackFriday: In Praise of the Independent Cinema of the 1980’s”. Film Independent. Film Independent, 2017. 18 November 2016. Web. 26 July 2017.

Advertisements Share this: