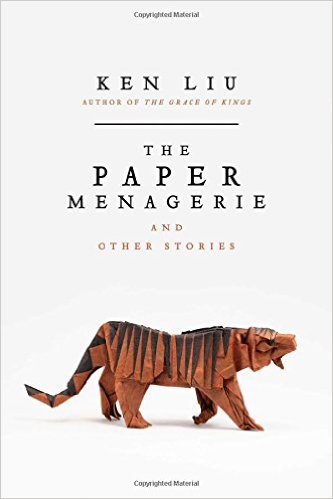

I don’t know why I held off for so long on reading Ken Liu. Actually, that’s a lie: I know exactly why it took me so long to finally read The Paper Menagerie, and it’s because I was, quite simply, jealous. When I first learned of Liu and The Paper Menagerie, it was in the context of “The Paper Menagerie” the short story, and the fact that it had just won The Hugo, Nebula, and World Fantasy awards, which was unprecedented like what-the-fuck. And instead of being happy for him, glad that Asian-American writers were getting more recognition, I was pissed.

Here’s the thing. The Chinese American community is incredibly cutthroat, parents always pushing you to be ninety-ninth percentile because there was only so much room up at top, you had to the best or other it’d be game over, community college and a lifetime of disgrace for you. When I learned that Liu was a critically-acclaimed Chinese-American speculative fiction writer, my initial thought wasn’t wow, that’s cool, I’m so glad he’s doing that and I hope I can be like him one day; it was well, fuck, how the fuck am I supposed to compete with that?

The sad truth is, there aren’t a lot of prominent non-white authors in speculative fiction, and of the ones who do manage to make it into mainstream fame, it’s usually because they offer something different: another perspective, a glimpse into another culture, something different. Authenticity—write what you know, except that imperative also comes with an unsaid clause: write what you know others will want to read. And in a mostly white society, that is foreignness. If you’re going to be a non-white writer in English, it’s expected that you sell yourself accordingly. Raised on American cartoons and with a grasp of Mandarin at roughly a fourth-grader’s level, how was I supposed to do any of that—especially after people like Ken “practically Triple Crown of Sci-fi” Liu had been there?

So yeah, there was jealousy. Jealousy that turned out to be well-founded—Liu is a great writer—but which was, pleasantly enough, swept away by something else, aka my sheer enjoyment of this book. I’m still disgruntled I’ll never be the next Ken Liu, but it’s the same way I’m disgruntled I’ll never be the next Neil Gaiman. Some things, you just learn to accept as pipe dreams.

So. Onto the book itself. Because of the Hugos and his translation work on Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem (a book that I have unsuccessfully tried to read multiple times), Liu is more associated with science fiction than with fantasy. Whatever these terms mean though, it does seem to me that his work falls more on the “hard” end of the hard (meticulous description of the quantum physics of time travel, because everyone who reads sci-fi is a scientist)/soft (wibbley wobbley, timey wimey stuff—who actually cares?) sci-fi spectrum. And there’s a problem I have with so-called “hard” speculative fiction, in that the attempt to explain the workings of the world, authors tend to lose sight of the character. It’s part of the reason I couldn’t finish Three-Body Problem, part of the reason I couldn’t quite enjoy Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life, and why I’ve never read much sci-fi in general, to be honest. I like science a decent amount, science and thinking about cool science-y stuff like Schrodinger’s cat and string theory and what the hell they all mean. When I come to fiction, I come for the people, not the literary equivalent of a thought experiment—which, unfortunately, is what a lot of hard sci-fi (and occasionally fantasy) feels like to me.

Not Liu, though. His worlds are certainly well-researched and carefully constructed—the man puts works cited in his author’s notes, for God’s sake—but instead of flaunting this meticulous construction, Liu wisely leaves it in the background. There’s a richness of world, yes, but it never overwhelms the richness of character. Take, for example, “The Regular,” a neo-noir about cybernetics and murdered prostitutes that explores the relative pros/cons of human enhancement. It’s a favorite sci-fi theme—what separates human and machine, how does technology affect who we were—but Liu holds back on the Heidegger and posthumanism babble, choosing to focus more on the characters’ emotional dilemmas. The Ghost in the Shell, philosophising-on-the-nature-of-humanity elements are present, yes, but it’s the characters—cyborgized detective Ruth Law, the daughter she failed to rescue, and the prostitutes she hopes to now rescue to make up for that earlier, devastating failure—who are at the center of the story. Which, I suppose, is a pretty good description of Liu’s work in general, which—for all the delicious worldbuilding it contains—operates mainly on a more personal level. Steel exterior, but also huge heart; “The Paper Menagerie” itself had me crying through the second half of the story. So yeah, would definitely say it earned that Nebula/Hugo/World Fantasy award.

And the non-white bit, the “Liu” part of “best-selling author Ken Liu”? An initial attraction for me yes (again, the lack of non-white characters in speculative fiction), but also initially a source of potential worry. The Asian element is certainly present, with stories referencing The Monkey King and the creator goddess Nuwa, but they exist among other elements: cybersurveillance under capitalism, the nature of consciousness, maternal and filial guilt in turn, etc. They’re definitely Asian stories, but they don’t feel pandering or self-orientalizing about being Asian stories, is I guess what I’m trying to say.

As an Asian book then, one of the elements I appreciated most about The Paper Menagerie is how Liu uses speculative fiction to explore the ever-present problems of #immigrantangst. “The Paper Menagerie” is probably the most explicit of those concerning that theme, dealing as it does with the archetypal biracial kid who rejects the non-white part of his heritage to fit in with his American peers, but I also really enjoyed “All the Flavors”—subtitled “A Tale of Guan Yu, the Chinese God of War, in America” and which is set in the Gold Rush America— along with “The Literomancer,” which was set in the Cold War Taiwan. In both stories, we see Western characters interact with Chinese culture, with all the mistrust and tentative uncertainty that comes with that exchange. There’s the expected racism, yes, but there’s also a surprising (and gratifying) embrace of cultural exchange. Chinese culture isn’t a monolith, Liu reminds us, shaped as it is by past invasions and cultural changes, and adopting new cultural experiences—so long as that adoption isn’t coerced or violent—doesn’t necessarily mean giving up old ones. A fox spirit gains a metallic body, humans evolve from mortal bodies to immortal ones to waves of energy, and a woman accidentally destroys the physical form of her soul—-and yet instead of dying as expected when her soul melts from ice to water, she survives. You can change form but still retain yourself. And hey, as someone’s lived in America since she was four, who grew up watching Journey to the West along with Powerpuff Girls and a truly obscene amount of anime, maybe I’m biased, but that’s a damn powerful thing to say.

So you know, congrats, Ken Liu. You’re a better writer than I am; I can and will concede that with minimal shame now, because there are just some people you can’t compete with.

Advertisements Share this: