This describes a reset – something in the nature of an eclipse you might say.

It was just a great bit of producing.

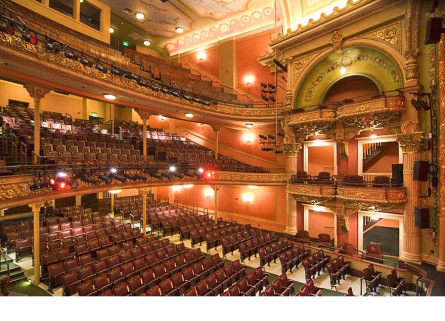

The Colonial Theatre, entrance on Boston Common. The show opened last night and the reviews were pretty tragic. A rumor went around that our star had at some time offended men of the fourth estate and they had been waiting to pounce to their revenge. True or not, the kind of stuff that closes shows on the spot had been written.

It was my first job in America and I had heard the stories about what happens when the reviews are less than ecstatic. The mood inside the theatre was despondent and a desultory rehearsal was proceeding onstage. Distinguished New York actors were going through the motions while the director tried to tweak new life into the proceedings, but there hardly seemed any point.

I stood at the back of the orchestra stalls observing. I watched the rehearsal. This was Waiting in the Wings, Sir Noel Coward’s last major play, the one he wrote for his senior actress friends, set in a retirement home for older theatrical ladies. The rehearsal lacked spark because everyone knew that whatever we did, it was over.

The theatre was empty, and the house lights were up. Atmosphere is everything, isn’t it? With a full house, the action on the stage lit by sympathetic illumination, the glow spilling into the auditorium, the gilt on the proscenium glisters and glamours an evening’s entertainment. Here the workaday lighting cast the very theatre in drabness.

Then Alex Cohen arrived.

Bit of back story here. On his 21st birthday Alex Cohen came into an inheritance, he immediately set about producing a show. It was Ghost For Sale and it closed after six performances. He lost a lot of money on it. He then immediately got involved in producing Angel Street (later filmed as Gaslight), and he made his money back. It was to set a pattern of ups and downs that he pursued for the next sixty years.

Alex Cohen in the time that I knew him, was one of the Grand Old Men of Broadway, Waiting in the Wings was his 101st Broadway show and his last. He was the man who said: “If God had meant me to ride in taxis, he wouldn’t have invented limousines.”

He was a great man of theatre, but there is no way you could say he was a well man. In his eightieth year he looked somewhat like a giant Halibut on a bad day, and his walk was a lumbering progress, his breathing like the early days of steam technology.

Alex lumbered in the auditorium and down the center aisle. Reaching row G he spread himself across a couple of seats and pulled out a cell phone. He began a conversation which started quietly, but grew loud in volume when the person on the other end of the line seemed to have said something that angered him. Suddenly I heard, “Listen, ASSHOLE! I told you, the message is no discount from any source! Get your ass down to the box office and buy a ticket, and if you’re too cheap to do that you’ll miss the best show of the season!”

The actors, 10 veteran Broadway actresses and a sprinkling of movie stars, all heard it too. The rehearsal slowed, faltered and finally stopped. All the ladies of Broadway staring, mesmerized by the conversation proceeding in the middle of the orchestra stalls in the empty front of house of the ornate, historic, Colonial Theatre in Boston.

Alex continued. He was, I believe the correct American vernacular is … “ripping the publicist a new one.” It went on and on. The actresses drifted to the front of the stage, watching and listening open mouthed, Michael Langham, the director who had once been a protege of Guthrie’s also turned away from the stage to listen slack-jawed as Alex gave ever more furious energy to the cell phone he gripped in his angry hands.

I watched too from the shadows at the back of the orchestra. From that vantage point I saw an example of what Peter Brook has defined for us as “Holy Theatre” which he says is, “The invisible made visible.”

Little by little the cloud of grey despondency, the gloomy resignation that attends the prospect of returning again to the wonderful world of unemployment, the defeat that is a flopped show… little by little this atmosphere began to transform.

It began with the lighting. The houselights did not dim, nor the stage lights brighten, but the darkly illuminating principle of a discouraging reception was obscured, then obliterated, to re-emerge as total confidence and certainty. The gilt on the proscenium began to glow in subtle shades, and the metaphysical gas of confidence oozed around the theatre. You could feel it seeking hollows and shadows in the dressing rooms, in the understage cross-over where costumes were set for quick changes, even in the box office where I fancy the phones began to ring. It rolled too in a visible/invisible wave across the seats of the orchestra to the stage where it broke over as fine a collection of Broadway dames as were ever gathered, as simultanously the thought erupted in all minds, “Oh! Maybe we won’t close at the weekend?!”

It began with the lighting. The houselights did not dim, nor the stage lights brighten, but the darkly illuminating principle of a discouraging reception was obscured, then obliterated, to re-emerge as total confidence and certainty. The gilt on the proscenium began to glow in subtle shades, and the metaphysical gas of confidence oozed around the theatre. You could feel it seeking hollows and shadows in the dressing rooms, in the understage cross-over where costumes were set for quick changes, even in the box office where I fancy the phones began to ring. It rolled too in a visible/invisible wave across the seats of the orchestra to the stage where it broke over as fine a collection of Broadway dames as were ever gathered, as simultanously the thought erupted in all minds, “Oh! Maybe we won’t close at the weekend?!”

Alex continued his tirade of insult and cajolement ripe with expletives, “What the hell do you mean suggesting a discount?!? This is the best goddam show to hit the New York in living memory!” The theatre was silent. Alex, a producer not an actor, but a showman, an original, he knew his audience that day and he had them spell bound. With a final, “Asshole!” yelled at full throttle at the publicist, Alex pounded the off button on the phone, took a breath, lumbered to his feet and processed slowly up the aisle and out of the theatre, saying not a word as he went.

There was a long beat of silence, then Michael Langham turned to the company and said with quiet assurance, “Well, shall we continue?” The ladies answered with optimistic smiles and the rehearsal began with new purpose. Four weeks later the show opened at the Walter Kerr Theatre on Broadway in New York, garnered better reviews than in Boston. Award nominations followed, and a transfer to the Eugene O’Neil theatre round the corner. It was an impressive six month run. And that phone call had everything to do with it.

Waiting in the Wings was Alex Cohen’s last show. When he went they dimmed the lights on the Great White Way.

Later I pondered this incident. Admirable is the temperament that refuses to accept defeat, that exudes infectious positivity no matter what. But there was a lot of technique involved as well. It took me a long time to wonder about it, and only now writing many years later am I more than 95% sure … there was no publicist, there was no-one on the other end of the phone in the Colonial Theatre in Boston that day.

Share this: