I’ve written bookish things recently, but have not kept up with my posts on reading.

I’ve written bookish things recently, but have not kept up with my posts on reading.

Here goes.

I recently read Alice Thomas Ellis’s elegant comic novel, Pillars of Gold. Ellis was the pseudonym of Anna Haycraft, the wife of Colin Haycraft, owner of Duckworth publishing company. Her novel The 27th Kingdom was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1982. And I love her hilarious columns about family life (she had seven children), published in four volumes as Home Life.

If you haven’t read Ellis, Pillars of Gold is a good place to start. This dark comedy, set in a gentrified neighborhood in London, begins with a paragraph in a local newspaper about a woman’s body found in the canal. The neighbors realize the corpse might be Barbs, an obnoxious woman who has been missing for weeks. Nobody misses Barbs. Nobody likes her. But Constance peeped in the window and noticed the plants were dead. What should they do?

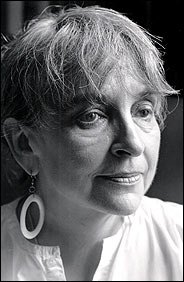

Alice Thomas Ellis

The attitudes of this mostly-autonomous community toward the police are comically revealed. Everyone guiltily agrees that someone might want to murder Barbs. Scarlet, an unhappy housewife married to an advertising executive, wonders if they should go to the police. Constance, a jewelry maker who deals in illegal goods and has lived a disreputable life next door, formerly with her shady brothers and late mother, says she’ll report it but changes her mind. And when Scarlet says that Barbs had no family except in America, Constance decides no one will miss her. The same is true of neighbors who attend a dinner party at Scarlet’s house. Everyone thinks Barbs might have been killed, but no one does anything about it.

Camille, Scarlet’s daughter, who constantly cuts school, reads the item about the murder at a bar. Soon it is the talk of her friends, who take advantage of Barbs’ absence by having a party in Barbs’ house. It turns out to be a bad idea because they, too, become increasingly uneasy.

Why does no one report that Barbs is missing? She was a liberal political activist, partly admirable, but extremely annoying to her neighbors. She comported herself as if she were beautiful, and this greatly irritates Scarlet, who finds her ridiculous. Some of the men might have slept with Barbs, too.

Ellis writes,

Barbs prided herself on her deep and politically informed compassion. She concerned herself about everyone–the neighbours, the tramps, the gipsies, the feral cats and the condition of the local trees. When the council had organized a festival to alert the people to the plight of Nicaragua, she alone of all the neighbors had climbed into the mobile coffee shop, which the council had provided, to drink Nicaraguan coffee and read the Nicaraguan posters which adorned the bulkheads and bulwarks of the van. She went on gay rights marches–although, as far as anyone knew, she was heterosexual–and was wont to punch the air with her fist at moments that seemed to call for affirmation or triumph. Sometimes she also uttered a cry which she had picked up somewhere: a kind of ‘Yah.’

We all know people like Barbs.

I am very fond of Scarlet, who wants to scream at the crumbs on the counter after breakfast. She worries constantly about pesticides and food, calculating vitamins in broad-leafed veg vs.r radioactivity, and is so exasperated with the details of housekeeping that she wishes she were dead.

She ought to feed the cat–and then there was the washing. The builder should be summoned to scrutinize the small growth on the pantry’s outer wall, and her husband had informed her that the bank had made another balls-up and requested her to deal with it. Tonight they were going to the theatre.

All this is beyond her, and she has no interest in going to the theatre.

Constance is also endearing, just back from a vacation in Greece, where her boyfriend Memet deserted her and left her with his family. She lives outside law and order–she mocks the council,”…benefactors of humanity and kidding themselves about the perfectibility of man–silly bastards…They got no grasp of reality.”

In their way, all the characters are realists, but what did happen to Barbs? Read on. It’s not a mystery, but events take an odd turn.

P.S. And I wondered (with no evidence at all) if Constance were based on Beryl Bainbridge, a close friend of Ellis. The community’s attitude towards the police reminds me of that of characters in Bainbridge’s novel, The Bottle Factory Outing.