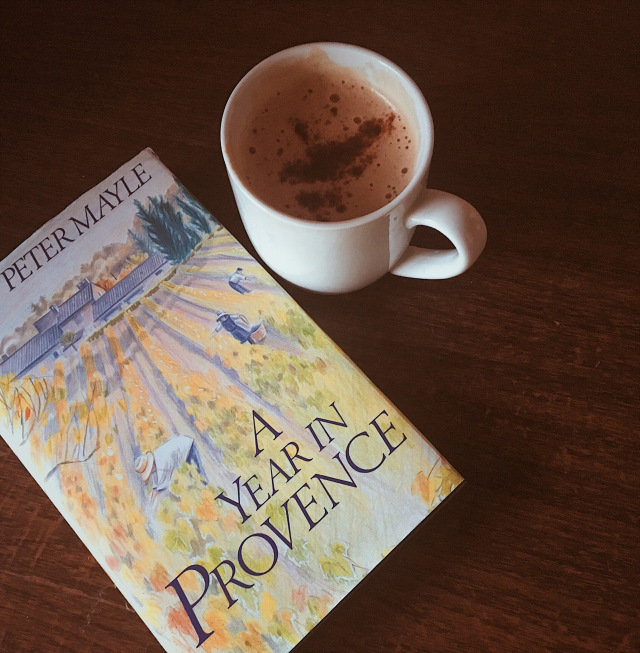

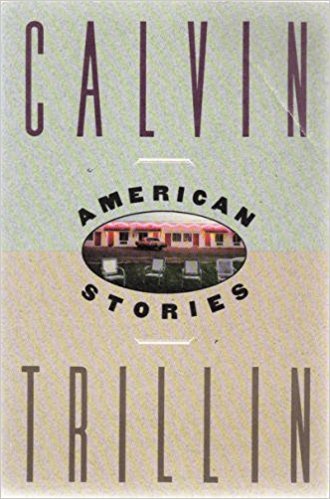

American Stories, from 1991, is a collection of twelve New Yorker pieces by Calvin Trillin.

I’ve read mostly Trillin’s humor writings, as well as his memoirs, which are kind of whimsical and have a certain amount of humor as well. Remembering Denny was the closest to being purely serious of all his books that I’ve read.

American Stories is about like the memoirs in that respect. There are pieces that are pretty much straight journalism, and there are pieces, or stretches within pieces, where the Trillin personality and wit are more in evidence.

Even the more serious journalism is not of the daily newspaper, just-the-facts, type, but of the long form magazine feature stories type, like you’d expect from The New Yorker. These are pieces that seek to provide psychological and sociological insight into a person or people and their world, while telling a compelling story. It’s a kind of journalism that Trillin excels at.

The first selection is Outdoor Life, the story of Ed Dyer and his relationship with Louis Conner. Dyer, it seems, is a pedophile, and Conner is a teenage boy.

I have sympathy for everyone in the story, yes including Dyer. I know it’s mandatory nowadays to hate pedophiles, and to compete with each other for who hates them the most by proposing more and more vicious torture for them and such, but a story like this leaves me with much more sadness—for all concerned—than rage.

Dyer insists—as I take it is not uncommon for a pedophile—that he genuinely cares for Conner. Again unlike most people, I don’t think that’s necessarily false. It’s entirely possible to have genuine favorable feelings toward someone you sexually desire and not to see them merely as an object for your sexual gratification. I assume that remains true even when that someone is a child. Heck, I saw a documentary on bestiality in which its practitioners stressed repeatedly in interviews how much they love animals, and how they feel an extraordinary emotional connection with animals that many of them have never achieved with another human being, and I have no particular reason to think they are all insincere.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the problem is that the younger the person is that you sexually desire, the more harmful it is—all else being equal—to have sex with them, and thus the more you’d be wronging them. A 2 year old has less capacity to meaningfully consent and to handle the myriad of physical and emotional consequences that sex carries with it than a 7 year old, who has less capacity than a 10 year old, who has less capacity than a 13 year old, who has less capacity than a 17 year old, who has less capacity than a 20 year old, who has less capacity than a 40 year old, and so on. There’s less brain development, less life experience, etc. There’s no bright shining line between a person who is 17 years, 364 days old and a person who is 18 years, 0 days old; it’s a matter of degree. (Which is not to deny that there can be justification for drawing such black-and-white distinctions in law, but I’m talking about morality.)

And if you genuinely care about someone, you ought not put them at risk like that. Just like if you have some contagious disease you shouldn’t be doing sexual things that can inflict it on someone else. Simple as that.

Simple, but not easy. But doing the right thing is not infrequently difficult. If you can’t have sex with the person you desire, or even the type of person you desire, without doing something egregiously wrong to them, then you just have to go without. Fair or not, there is no guarantee in life that it will be possible to act on your strongest sexual desires in morally acceptable ways.

To clarify, I’m not saying that because having sex with someone too young is inconsistent with doing what is best for them, Dyer and other pedophiles must be insincere in claiming they love or care for their underage partners. Being far from perfect rational beings, humans routinely manifest an inconsistency between their actions and their beliefs or emotions. I think it’s entirely possible to sincerely care for someone and to wrong them, because it happens all the time with flawed beings like us.

So when I look at a pedophile, I see someone who, in a sense, has a bigger moral burden than most of us in that they can’t have the kind of sex they naturally most desire without acting wrongly. It’s difficult, yet still obligatory, for them to refrain from that kind of sex, and when they prove unable to abide by such moral obligations it’s an ugly and sad situation for all concerned.

Telling a Kentucky Story is nominally about a Kentucky preacher/teacher/writer/farmer/pan-fried chicken cook named Tom Chaney, and how he got into trouble for letting people grow marijuana on his land. But really it meanders in a stream-of consciousness manner from story to story, in the style of the Kentucky storytellers at the heart of this piece.

It’s somewhat entertaining, but there’s a “you had to be there” quality to it. I suspect it would be far more interesting to hang out with these colorful characters and listen directly to their stories than to read this account of them.

There are some interesting bits in it about the changing attitudes toward drugs in a state like Kentucky, how marijuana has possibly become the number one crop grown in the state, even bigger than tobacco, and how being busted for it no longer has much detrimental effect on one’s reputation. Not that they would ever change the laws to reflect this growing acceptance.

They do have plenty of experience with such hypocrisy, Trillin points out, since the state is full of counties that are both legally “dry,” and plagued with severe alcoholism problems.

One of my favorite pieces in the book is The Life and Times of Joe Bob Briggs, So Far, the story of the rise and partial fall of Joe Bob Briggs, Dallas newspaper and then nationally syndicated movie review columnist who specializes in the trashiest of slasher films, exploitation films, and the like. Joe Bob, a 19 year old, thrice married, quintessential redneck, is the creation of Clark Kent-like newspaperman, and reviewer of non-trashy movies, John Bloom. He’s an unapologetic lover of gore, explosions, and breasts—the bigger and more exposed the better—irredeemably politically incorrect, and wildly popular among those who take him literally and share his tastes, and those who appreciate his brilliant satire.

The piece is entertaining just on the level of how funny it is in recounting Joe Bob’s antics. But it also raises a lot of intriguing, more serious, issues.

As one critic of Joe Bob points out, this is the kind of satire that generates the “Archie Bunker” problem, that is, a lot of the rednecks and bigots and such being satirized have no clue it’s satire, and so end up having their odious beliefs and attitudes bolstered by seeing them publicly espoused.

I agree a disturbingly high number of people misinterpret things like this and think figures like Archie and Joe Bob are heroes. (Though I’d say probably half or more of such people understand on some level that it’s satire, but pretend it’s intended literally in order to enjoy it more, as they might do with professional “wrestling.”) And I agree that their not getting it, and actually taking it as an endorsement of their views, has harmful consequences.

However, that’s true of basically all satire, at least all but the lamest satire. If you’re really going to have a rule that satire is out of bounds unless it’s so obviously not intended literally that even the dumbest person has to be able to recognize that, then basically you’re saying there should be no satire. Which would be fine if satire had no value whatsoever except the aforementioned disvalue of encouraging people who don’t get it to think their ignorant attitudes are being endorsed. But that’s not the case. Satire can make worthwhile points to the people who aren’t too dumb to get it. Not to mention the mere fact that it’s funny counts in its favor. Surely sometimes these and other positive factors can outweigh the negative factor of “But you’re just encouraging the stupid people!”

Relatedly, a Joe Bob opponent points out that the Joe Bob character allows Bloom to have it both ways. He can take credit for anything potentially praiseworthy that Joe Bob does—such as pointing out hypocrisy, defending freedom of expression, etc.—while excusing all the offensive stuff by saying that it’s obviously not intended literally but as satire, and thus is making fun of rather than endorsing such offensiveness.

I think this too is accurate, but I’m not sure it’s a bad thing. The border between satire and non-satire can indeed be fuzzy. I routinely skirt along that line myself in using dry humor, sarcasm, satire, etc. in how I express myself. There are plenty of things I say that are ambiguous as to whether they should be taken literally or as lampooning the kind of folks who would say such things literally, and at times that’s intentional or semi-intentional because I really do sort of believe what I’m saying and sort of not.

If I were Bloom and I created a Joe Bob character, I probably would intend some of his pronouncements literally, some as satire, and some in the gray area in between. If I had him dismissing all but Christian fundamentalists as devil worshippers or some sort of primitive tribal religion devotees dancing around a fire and making human sacrifices, it would be total satire, poking fun at the narrow worldviews of people raised in a certain conventional way within a majority religion who can’t or won’t accept that any alternative faith could be anything other than grossly wrong and/or weird. If I had him responding favorably to breasts, the bigger and more exposed the better, that wouldn’t be a way of ridiculing heterosexual males who like breasts, but would be intended literally, as I’m a huge breast fan myself (in both senses: I’m a huge fan of breasts, and I’m a fan of huge breasts), and I think it’s asinine that political correctness forces people to lie and pretend they don’t respond enthusiastically to a nice pair. And then there would be plenty of things in between, that I sort of mean, but that I’m also exaggerating beyond what I believe in order to make them funny.

So, yeah, I could see why a satirist could be accused of wanting to have it both ways. But I wouldn’t say, in my case, that there’s a dishonesty to that. It’s not like I’ll wait to see what response I get to the things I say, and if people like them I’ll respond like, “Yeah I really meant that,” and if they don’t like them I’ll respond like, “Oh come on. Don’t you get that I’m making fun of people who would say things like that? I’m actually on your side.” If people want to ask me whether I meant something I said literally, whether I was being sarcastic or satirical, or whether it’s in a gray area in between, I’ll gladly respond as accurately and sincerely as I can, and not base my response on trying to put myself on the same side as the questioner.

I don’t use satire as an excuse to express views that otherwise could get me in hot water with someone, because I’m perfectly willing to express those same views in an unambiguous, non-satirical way.

Which opens up the whole issue of political correctness run amuck. That’s a topic that’s more fitting for a book than for a fraction of a single short essay, so I’ll only touch on it here.

One of the things I most object to about political correctness is the way it is used to shut people up. The goal is rarely just to criticize certain expression, but to prevent it. It thereby violates a fundamental principle of free expression, which is that the proper response to objectionable expression is to add your own expression rather than to shut down the expression you don’t agree with. If you don’t like the way people are extolling the virtues of vanilla ice cream, then by all means make the best case you can for the superiority of chocolate, but as soon as you try to shut up anyone who argues for vanilla you’ve lost me.

So if those who are infuriated by Joe Bob simply explained what they have a problem with, I’d be more than happy to respectfully listen to them, and to open-mindedly consider where I agree and where I disagree with them. But of course that’s not what they do. They invariably jump from “We don’t like what Joe Bob wrote” to “We’re justified in using whatever means necessary—boycotts, marches, lobbying of newspaper editors, whatever—to have his column ended, keep his books from being published, and in general keep him from being able to communicate such offensive ideas to the public,” to which my response is an emphatic fuck you.

I suppose I agree with some of what might fall under the umbrella of “political correctness.” I agree with Molly Ivins (and many others), for instance, that there’s a key difference between satire that skewers the powerful and satire that skewers the powerless, and that the latter can be objectionable in ways that the former is not.

Think, for instance, of the difference between Charlie Chaplin making fun of Hitler in The Great Dictator, and Nazis making fun of Jews in Der Sturmer.

I don’t think that means that all satire—or criticism, etc.—of relatively powerless groups is out of bounds, but I think that means that you have to tread a lot more carefully depending on the target of your satire.

I would hope as a satirist you’d mostly ridicule the powerful and those who most inflict and benefit from the injustice in the world, but if you use 10% or 15% or whatever of your arrows on the dummies, hypocrites, and blowhards who don’t fit in that category, I’m fine with that.

For one thing, not all the powerless are all that powerless. There are plenty who have parlayed their status, often self-appointed, as leaders or representatives of the powerless into positions where they can wield power, and they not uncommonly do so in unjustified, petty, or self-serving ways. I’m not going to hold my fire against two-bit censors, university thought police, self-important media pundits, and the like just because they’re black, female, transgender, immigrant, etc., or claim to speak for such groups. If they’re behaving like assholes, and exercising power irresponsibly in their own little fiefdoms, they’re fair game.

But, yeah, if you only target powerless groups and their politically correct defenders, whether through satire or more literal criticism, that’s not cool. Right wing ridicule of that kind always gives me the creeps, and makes me instinctively align myself more with the politically correct folks that I otherwise mostly find annoying.

So is Joe Bob in his satirical manner guilty of attacking mostly victims rather than victimizers? Is he one of those obnoxious right wingers who incessantly goes after women, minorities, gays, and such, while giving more deserving targets a pass? Or at least over time did he evolve in that direction?

You can make a case for that. In the end, I’m still more of a Joe Bob supporter than critic, but he at least gets close to that line of overdoing the trashing of vulnerable groups while claiming it’s OK because it’s satire. Certainly his biggest controversies came when he was perceived as having insulted women and blacks and such, with the single biggest one, that cost him his column, being when he ridiculed the We Are the World fundraiser in a way that could be interpreted as trashing Africans in general, blacks in general, or starving people in general. (Though, again, there are always multiple interpretations possible. I seriously doubt Bloom hates black people or is in favor of starvation or whatever. More likely he was making fun of a certain hypocrisy or group-think in the We Are the World thing, or making fun of those who would make fun of the fundraiser.)

The essay also raises the question of just how much Bloom has been captured by Joe Bob. Ultimately he spends a lot more time on the Joe Bob stuff than on his non-Joe Bob journalism career. The most straightforward explanation for that is that that’s because he can be a lot more successful in a sense and make a lot more money as Joe Bob, but there are strong hints of something darker going on, something that put me in mind of those horror movies where the ventriloquist comes to believe his dummy is a real, conscious being, and who gradually comes to be dominated more and more by the dummy’s make-believe personality.

Anyway, there’s plenty more I could say about these and other matters related to The Life and Times of Joe Bob Briggs, So Far, but let’s move on.

Next up is Rumors About Town, which is exactly the kind of story you’d see on CBS’s 48 Hours Mystery show.

It’s not as deep as some of the pieces, though Trillin does include some sociological observations about the past versus present (or fantasy versus reality) of small town life in the Midwest, but it’s as entertaining a page-turner as any selection in the book.

Set in Emporia, Kansas, the tale concerns a family man who is allegedly murdered in a hold-up. Over time, lots of interesting facts and allegations dribble out: The man was a hothead who certainly emotionally abused his wife and may have physically abused her. The wife had a well-earned “reputation” and had had affairs with probably dozens of local men—many married themselves—including the local minister. The minister’s wife had recently died under suspicious circumstances.

And on and on. Lots of racy stuff. I especially liked the way one of the main concerns of many of the town’s most prominent men was just how much law enforcement and the press knew about the wife’s affairs, and just how much of that—how many names—might eventually be made public.

A Couple of Eccentric Guys is Trillin’s profile of Penn & Teller. At almost 40 pages, it’s about as in depth as a magazine piece could realistically be, covering the performers’ lives all the way from childhood through scuffling around at Renaissance fairs around the country, to worldwide fame.

It’s a fun piece, because the subjects are fun guys. Though in some respects vastly different from each other, Penn and Teller share backgrounds as kids who were always nonconformists, always outsiders, always loners, and who developed traits of perfectionism, attention to detail, and a willingness to endlessly practice the same things over and over that would be completely foreign to people who grew up with normal social lives.

You also get more flashes of the Trillin humor in this piece than in most in this book. He recounts for instance, that upon once meeting Harry Blackstone, Jr. on the street, he asked him if he could please turn his 13 year old daughter into an elephant. (Blackstone’s apparently pretty fast on his feet himself, as he responded that that would not be such a good idea, as an elephant is one of the very few things that requires more upkeep than a teenager.)

Though I haven’t followed Penn and Teller’s careers all that closely, I’m certainly aware of them and some of their exploits, and I’ve always liked them and found them interesting. After learning more about them, I like them more and find them more interesting.

Next is Competitors, about the legal dispute between Häagen-Dazs and Ben & Jerry’s.

This feels like a step down. It’s one of the shorter pieces, and while the principles (Reuben Mattus in the case of Häagen-Dazs; Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield in the case of Ben & Jerry’s) are somewhat interesting, they aren’t as intriguing as Penn & Teller or John Bloom/Joe Bob Briggs, and it feels like Trillin just didn’t have as much to say about these folks, didn’t feel as inspired to delve into them in depth.

They are, as Trillin relates, very different types of entrepreneurs. Mattus is an elderly immigrant who has been in the ice cream business for decades, who started penniless and built up to a fortune through long hours, hard work, and innovative ideas (he pretty much invented the concept of “premium” or “gourmet” ice cream). Cohen and Greenfield (mostly Cohen; Greenfield “semi-retired” early and has since had only a minimal role in the company) are the famously hippie, socially conscious entrepreneurs.

To further complicate the picture, Mattus was bought out (for tens of millions of dollars) by Pillsbury, though he remained chairman of Häagen-Dazs. So the dispute is sort of Ben & Jerry’s versus Mattus, and sort of Ben & Jerry’s versus Pillsbury. (Of course, Ben & Jerry’s much prefers that it be perceived as the latter, as it’s much easier to villainize a mega-corporation like Pillsbury than an embodiment of the American Dream like Mattus.)

What is the dispute? Evidently, as Ben & Jerry’s sought to expand from their Vermont roots, they were hampered by certain agreements Häagen-Dazs had with distributors that they would not carry any premium ice cream brands other than Häagen-Dazs. Such agreements are not always illegal; on a case-by-case basis it has to be determined if they unfairly limit trade so as to create too much of a monopoly situation.

Really not enough is presented in the article to be able to say who is right (plus I don’t have the background knowledge of this area of the law even if I did have all the relevant facts), but my gut says Mattus’s assessment is probably about right: Legally it’s likely a fairly close call, but in reality there were plenty of other distributors and other stores, and Ben & Jerry’s could have expanded and been only minimally at most impeded by the Häagen-Dazs agreements, but they saw a chance for a public relations bonanza by painting themselves as the underdog victim against big bad Pillsbury.

One thing I’ll say is that the piece made me hungry for ice cream, premium or not. I love ice cream.

Right-of-Way is another true crime murder story, though not a mystery. (Trillin had authored a previous collection of articles called Killings that is all murder stories, so this is something of a niche of his.)

Two women get into a property dispute in a semi-rural area an hour or so outside of Washington, D.C. Though they differ in social class and other ways, they both have come to the area fairly recently to get away from it all and pursue a quieter, more peaceful life. One is accompanied by her husband; the other has recently hired a farm manager—a burly guy twenty years younger than her with a mixed local reputation as possibly a bully, possibly not, whom she is also soon dating.

The dispute is over a “right-of-way,” which, as I understand it legally, is a part of what would otherwise logically seem to be one party’s property but because it is the only access or only convenient access to a second party’s property, the second party has the right to use it as if it were theirs to come and go.

They go back and forth over various petty things connected to the right-of-way, and ultimately the woman with the large farm manager decides to take her legal rights to the limit and build a road the maximum allowable width on the right-of-way, which of course the other woman vehemently opposes. (You can argue over whether it’s a nice thing to do or not, but unless there’s some nuance I’m missing, legally the woman putting the road in seems clearly within her rights.)

The farm manager guy shows up with a bulldozer and starts work on the road. The angry neighbor woman shoots him dead with a shotgun.

The only people present, except the dead guy, are her and people related to her. Yet the story they tell really isn’t all that exculpatory. Yeah, there’s a claim that she thought he would pull a gun himself and shoot her if she didn’t shoot first, but really that’s at about a George Zimmerman level of plausibility if not weaker. It certainly sounds like she just shot him dead in a rage as a further escalation to the escalation of bringing a bull dozer onto the property.

Yet she is acquitted. Actually there’s a hung jury first—11-1 in her favor—and in the retrial she is acquitted 12-0. Some of the local people observe, and it sounds accurate to me, that the jury members must have been swayed by factors that technically aren’t relevant to her guilt or innocence—basically whether they preferred her or the guy some of them regarded as a menacing bully and his rich cougar girlfriend.

I’m left with two reactions to this story. One is that I find it troubling that the legal system works this way, that jury decisions are in part popularity contests, that trials aren’t rational, accurate, wholly objective applications of the rules to a set of facts. I don’t mean in any way that I’m surprised that they aren’t (of course I’m not), or even that I think any other system is necessarily better than ours (I don’t know enough about the alternatives to have a confident opinion one way or the other), just that it’s unfortunate.

My other reaction is that this kind of story triggers what I suppose is a sort of phobia of mine, which is serious neighbor problems. If I’m in a situation with really loud neighbors, litigious neighbors, neighbors I suspect might be vandalizing my property, whatever, I really don’t have confidence in my ability to handle such disputes.

Being a proponent of nonviolence, I want to deal with any conflict of that kind without violence, where violence includes not only a physical fight or threatening them with a gun or whatever, but also involving the state, since the state’s coercive power is in fact violence, and when one calls upon it, one is using violence by proxy. But I just don’t think I’m very good at always getting my way—even when I’m right—nonviolently, especially with obnoxious people inclined to pursue their self-interest as far as they can get away with. I don’t feel like I’m good at schmoozing with people like that, making little compromises that I’m in no way obligated to make, knowing how to push their buttons to get them to stop doing what’s causing the problems, etc.

So my inclination is to just tolerate such situations as long as I can, and when it becomes too much for me, to leave. That’s one of the few advantages of renting, and one of the things that gave me pause about finally becoming a homeowner late in life, that the cost (financial, psychological, etc.) of moving when you’re an owner is so much greater than when you’re a renter, so you’re kind of trapped. So my nightmare is that I go through the whole, long, laborious, expensive process of buying a house, I move in, and I find out that next door are a bunch of bikers who throw loud parties all night every night and basically dare their neighbors to do anything about it.

Thankfully that hasn’t happened, at least not yet. But reading a story like this makes me think that had I been in the shoes of either of the parties in this story, despite the cost and inconvenience of moving, and despite the pride thing of not wanting to back down, I hope I would have simply left well before it reached the point of gunfire. I’m sure there are other areas in small town Virginia or whatever their ideal is where they can find the peace and other amenities they want without having this bullshit to deal with.

Goldberg Can Go Home Again is probably the selection closest to the Trillin humor style I’m used to, in that it’s written in the first person, it’s about someone he knows personally (I was going to say a non-celebrity or someone not famous, but the subject of the article is a bit famous, albeit well below the level of Penn & Teller or Ben & Jerry), and he’s going for laughs—I’d say largely successfully—throughout the piece.

The “Goldberg” of the title is Larry “Fats” Goldberg, a school chum of Trillin’s from back in his Kansas City days, and a decidedly eccentric, colorful character.

Goldberg has achieved a certain level of notoriety as a pizzeria impresario in New York, winning awards and such. But he has many dreams and speculations about new ventures, including pursuing certain inventions (e.g., a conical pizza, or a special holder so you can more conveniently handle pizza without getting burned), writing books (e.g., an edible diet book), or moving back to Kansas City.

Goldberg, who topped out at 320 pounds, shortly after college dropped half of that (or what Trillin thinks of as losing the equivalent of one Rocky Graziano in his prime) by walking a great deal and changing his eating habits (though his diet allows him a certain number of “cheating” days throughout the year, where he can go back to his old ways without regret and gobble up all his favorites).

Evidently he is the sort who just by being himself and not trying to be funny constantly makes hilarious and oddball statements. Trillin describes himself as Goldberg’s Boswell. I’d say maybe he’s Ricky Gervais to Goldberg’s Karl Pilkington.

This is a fun, light piece from start to finish. Quintessential Trillin.

You Don’t Ask, You Don’t Get is a moderately interesting account of the rapid rise and total fall of the ’50s early rock group Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, and the endless bickering over royalties for their one hit song, “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?”.

Bottom line: Lymon was an utterly pathetic loser (junkie and pimp while still in grade school, panhandler and thief once his career went in the toilet, completely dishonest and dishonorable in his personal relationships, married at least three times—apparently concurrently—and dead at 25); his bandmates were little better; as show business weasels go, record company weasels are perhaps the most weaselly of all show business weasels; and these fights over royalties (see also Rian Malan’s essay The Lion Sleeps Tonight about the song of that name) can get so complicated and last so long that it’s a wonder anyone involved is still alive if and when they ever get settled.

I’ve Got Problems is the story of Art Kirk, a Nebraska farmer and anti-government right wing kook who got into a deadly firefight with a SWAT team.

His was a depressingly common situation in many respects, and a very rare one in others.

Kirk was a hard-working, simple-minded farmer with a love of guns who found himself hopelessly in debt when the rural economy fell apart. His life situation left him in a confused rage, which right wing groups like the Posse Comitatus exploited to convince him that that rage should be directed at conspiratorial enemies including the government, the banks, and the Jews, and that they could teach him how to easily solve his problems (basically by simply refusing to pay the money he owed, and citing as justification various outlandish legal claims no one outside of such extremist groups recognizes as having any validity).

So far that could describe a large number of troubled farmers. Where he differs from all but a tiny fraction of these farmers is that his situation escalated to the level of gunfire and death.

It’s a sad situation all around. I think a very common reaction (especially when we’re talking about an unsympathetic character—a gun nut spewing anti-Semitic rhetoric and shooting at cops) would be that he’s an adult, he borrowed the money, he’s obligated to pay what he owes, so fuck him.

A part of me feels that way (I too grew up in a fiercely capitalist society, and I unavoidably absorbed some of that “personal responsibility” attitude about debts and such)—maybe 20% of me.

But I think you have to balance that with many other factors. One is how much deception and trickery was involved in getting people to borrow the money they did. Another is whether other parties who behave at least as irresponsibly as the farmers are treated the same by the system, or whether they get more “do overs” instead of being held strictly to pure capitalist standards.

Of course this same type of dubious borrowing set the stage for the recession/near depression that occurred decades later and involved homeowners, not just farmers, getting trapped in unsustainable debt—in some cases, to varying degrees, because they behaved in excessively greedy or otherwise blameworthy ways, and in other cases not—where the question again arose of who would be bailed out and who would not.

I agree there’s a problem if farmers—or anyone—can borrow whatever money they want and then be relieved of any obligation to pay it back if things turn against them. But surely there is a middle ground between that and a hard core absolutist capitalist position that no amount of debt can ever be forgiven for any reason. I mean, the concept of bankruptcy is an example of something in that middle ground.

I think in general we need to recognize that there’s a very large element of luck in who comes out on top and who comes out on the bottom. Two people, at different times in different circumstances, might borrow heavily to invest in farm land. Let’s say they’re exactly equal in terms of personal integrity and responsibility about debts, intelligence, honesty, willingness to work hard, etc., but due to factors beyond their control—and thus, relative to them, basically luck—like market forces and the timing of when prices go up and down, what years the weather is good for farming and what years it isn’t, etc., one of them ends up a multimillionaire and one ends up with nothing except more debt than he could pay off in multiple lifetimes.

I don’t say in a case like that that we should undo these outcomes and put the two people back to where they are equal. I don’t think we should make it so there are no winners and losers in life. But I reject the notion that “winners” like the lucky guy here are entitled to every penny they ended up with, that it’s unjust to tax them at a higher rate, etc., while “losers” like the broke guy got what’s coming to them and deserve no pity. I believe in a graduated income tax and programs to assist the less fortunate and such, not to fully eliminate the unequal outcomes, but to smooth out some of the extremes and reduce the massive human suffering that would occur under a completely unforgiving system of capitalism.

Kirk and people like him bear some responsibility for their plight, but not a hundred percent responsibility. And even if they did, while justice might not then require giving them a break of some kind, surely simple human compassion and charity would.

Covering the Cops is a profile of Miami Herald crime reporter Edna Buchanan. It’s an interesting exploration of an aggressive form of journalism that only a certain kind of person is capable of doing well. Among other things, it requires maintaining constructive enough relationships with law enforcement to get the cooperation you need (without falling back into the old school method of simply being blatantly pro-cop and conveniently looking the other way when confronted with their misdeeds), and pushing victims, suspects, witnesses, victims’ family members, etc. for interviews right up to (some would argue beyond) the line where it becomes harassment, no matter how much abuse you take for it.

The final piece in American Stories is Zei-Da-Man, an account of the tragic death of young John Zeidman.

Zeidman was the son of Washington mover-and-shaker lawyer Philip Zeidman. While not a hopeless fuckup, he was a largely directionless youth who even his own family admitted was for the most part a pain in the ass. That is, until he left home, spent some time working in Boston, started college at Duke University, and especially traveled to China for an extended stay.

I’m always a little suspicious of stories like this, where the reaction to someone’s death is that it came at just the point they had turned their life around, just the point when the trajectory of their life was headed straight up and they were about to make great contributions to the world. That theme is a tempting one regardless of whether it is also an accurate one, because it fits with the general tendency to focus on a dead person’s good points rather than bad points. So you highlight the evidence that they were on the right track and headed toward a bright future, and ignore any contrary evidence.

But for what it’s worth, I found this particular token of that type of story to be more believable than not. It really does sound like Zeidman had matured a great deal, that he had become a much more functional, competent, dynamic person, that his relationships had improved noticeably, and that people were now responding much more favorably to him.

And then he contracted a very bad from of encephalitis from a mosquito bite in China. The account of his treatment in China, the way his parents and others responded, the decisions that had to be made, how people coped with what was happening, etc. is quite compelling stuff.

Trillin just flat out knows how to write stories like this, even deadly serious stories. There’s more to him than an excellent sense of humor.

There are many things that stand out about this account. One is the way Philip Zeidman, the father, has to come to grips with the fact that taking charge of a situation, and throwing all your energy, will, intellect, resources—material and otherwise—into it, does not guarantee you will achieve the outcome you seek, a lesson that was basically the opposite of what his life had taught him up to that point.

Another is the way the medical personnel acted with such dedication and compassion, and responded to Zeidman as if he had some rare sort of charisma even when in a coma. The Chinese nurses were as devoted to him as if he were a close family member. Then after he was brought back to the United States, and the physicians and his parents made the difficult decision to “pull the plug,” the American nurses banded together in protest and tried to stop that decision from being implemented, as they couldn’t bear to give up hope.

Then again, there’s also a potentially creepy political element at play. There were parties in the United States and especially in China who saw the Zeidman situation as potentially having major implications for the reputation of their country and for U.S.-China relations, and so some of what happened, and how it was perceived, was carefully stage managed. For instance, how much of the seemingly highly admirable behavior of the Chinese involved in Zeidman’s care was spontaneous and sincere, and how much was ordered from on high by a totalitarian government for strategic, public relations reasons?

I tend to think a good percentage of the “feel-good” aspects of this story are legitimate, but the things that happened once it became a matter of prominence with political implications are a lot more iffy. Maybe some or even most of what people did and said from that point on was still genuine and from the heart, but it’s hard to have as much confidence about that.

A solid thumbs up for American Stories. Trillin is a fine journalist, a fine storyteller, and it’s a treat to accompany him through these various informative, thought-provoking, moving, and/or funny—and consistently engaging—tales.

Advertisements Share this: