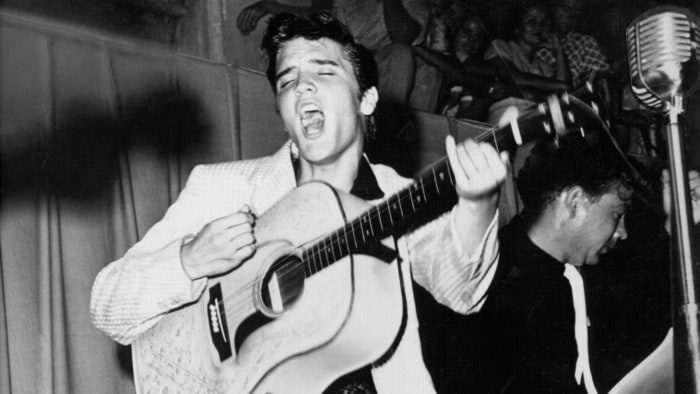

Elvis Presley. . . . . chicken á la King. Photograph: Getty Images

Elvis Presley. . . . . chicken á la King. Photograph: Getty Images

When people ask me what I was doing when Elvis Presley died – 40 years ago on August 16 , I can remember precisely. I was cooking – or failing to cook – my first chicken. I had just moved into a tiny bedsit in Tralee, where I was working as a cub reporter, and was trying out the dwarf oven in the place. After several hours, I was ready to tuck in when the news came on the radio. The King was dead. So was my chicken, but only barely. When I cut into it, it resisted. I picked up the half-raw carcass and dumped it in the bin. (Luckily, I hadn’t inflicted my culinary experiment on guests.)

I decided I needed to learn how to cook. I had moved out of home about two months previously, a home where I’d never learned to boil an egg, despite, or perhaps because, my mother was an accomplished cook. I had enjoyed a brief interest in baking in my teens and produced industrial amounts of ginger cake but I couldn’t live my life by the Marie Antoinette maxim, now could I?

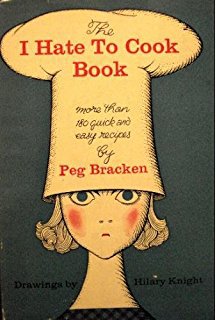

That’s when I found The ‘I Hate to Cook’ Book by Peg Bracken. Published originally by Harcourt Brace in 1960, my edition is a Corgi reprint dating from 1977. In a recent house move I rediscovered it, dog-eared, grease-stained, the pages turning to mottled yellow. (Corgi Books used very cheap paper.) Despite that, it had the look of a cherished item.

My copy fell open naturally to page 17 – Skid Row Stroganoff – a recipe I’d clearly returned to many times. “Brown the garlic, onion and beef in the oil,” Peg instructs me. “Add the flour, salt, paprika, mushrooms, stir, and let it cook for five minutes while you light a cigarette and stare sullenly at the sink.”

For her Hootenholler Whisky Cake, the first instruction is this: “Take the whisky out of the cupboard and have a small noggin for medicinal purposes.” Later on, when the cake is sitting in the fridge, where she said it would keep forever, you could buck it up by “stabbing it with an ice pick and injecting a little more whisky into it with an eye-dropper”.

Ah yes, that’s why I loved this book – not just for the recipes but for the writing.

The book was aimed at the woman who considered cooking a chore not an art, the housewife who had to dish up meals every day of the week on demand. “Never compute the number of meals you have to cook and set before the shining little faces of your loved ones in the course of a lifetime,” she advised. “This only staggers the imagination and raises the blood pressure. The way to face the future is to take it as Alcoholics Anonymous does; one day at a time.”

Drink is a constant motif.

Bracken acknowledged the social pressures attached to being the hostess with the mostest. “When the sun has set and the party starts to bounce, you want to be in there bouncing too, not stuck all by yourself out in the kitchen, deep-fat frying small objects or wrapping oysters in bacon strips.”

She had little time for canapés: “. . . though I don’t like to pick on something so much smaller than I am, it is hard to say a kind word about the Canapé. If canapés are good, they are usually fattening; and they are also expensive, not only in themselves, but in the way they can skyrocket your liquor bill.”

She had an allergy to “big fat cookbooks” full of what she called “terrible explicitness”.

“Pour mixture into 2½ qt saucepan,” they’ll say, she complained. “Well, when you hate to cook, you’ve no idea what size your saucepans are, except big, middle-sized and little. Indeed, the less attention called to your cooking equipment the better. You buy the minimum, grudgingly, and you use it till it falls apart.”

Bracken tried half-a-dozen editors, all men, before the book was accepted by a female editor at Harcourt Brace. It sold 3 million copies in its time and Bracken went on to write 11 more books including I Try to Behave Myself on etiquette and A Window Over the Sink, a memoir.

The ‘I Hate to Cook’ Book was reissued in 2010, 50 years after its original publication, but to more modest success. The reason is simple. The 180-odd recipes depended on their quickness and easiness on a lot of “shop-bought stuff” – predominantly canned and processed ingredients.

Half the recipes featured tinned, condensed or creamed soups – mushroom, onion, shrimp, chicken, tomato, celery. There was usually one canned vegetable or more involved – mushrooms again, baked beans and peas and oodles of processed cheese. For desserts, evaporated milk and whipped cream featured as well as a high dependency on cake mixtures, rather than baking from scratch.

“We don’t get our creative kicks from adding an egg, we get them from painting pictures or bathrooms, or potting geraniums or babies. . .” Bracken wrote.

Starting out as an advertising copywriter, a sort of Peggy Olson of her time, Bracken belonged to a generation of post-war American female writers – the I Love Lucys of journalism – who were essentially humourists who happened to write about women and the home. A contemporary of hers, was Erma Bombeck whose column was syndicated world-wide, including in Dublin’s Evening Press, and whom I read and admired as a teenager.

Both revelled in the domestic sphere. They were queens of the sassy bon mot, inheritors of the wisecracking Dorothy Parker mantle.

Housework, Bombeck declared, will kill you, if you do it right. If the item doesn’t multiply, smell, catch fire or block the refrigerator door, let it be, she suggested. My idea of housework, she told her readers, is to sweep the room with a glance.

Bombeck came late to fame. “I decided that it wasn’t fulfilling to clean chrome faucets with a toothbrush. At 37, I decided it was time to strike out. ” When the last of her three children started school in 1964, she began to write. She was, she said, “too old for a paper route, too young for social security, too tired for an affair”.

Even at the pinnacle of her success – earning up to a $1million a year – she still did her own grocery shopping, cooking and cleaning. “If I didn’t do my own housework,” she said, “then I have no business writing about it. I spend 90% of my time living scripts and 10% writing them.”

Neither Bracken nor Bombeck could be described as proto-feminists. Bracken, especially, was subversive only in the way she usurped the assumption that all women actually liked cooking. She wasn’t advocating that they walk away from it; she was merely suggesting ways of faking it. But in their writing, if not their personal politics, both writers paved the way for sharply comic successors like Nora Ephron and Carrie Fisher who had that easy, breezy comic talent that scored highly with their female readers.

As Erma Bombeck remarked: “My type of humour is almost pure identification. A housewife reads my column and says, But that’s happened to me! I know just what she’s talking about!’ ”

Peg Bracken had the same quality, a way of including her reader, making her part of the club. “This book,” she declared in the introduction to The ‘I Hate To Cook’ Book, “is for those of us who want to fold our big dishwater hands around a dry Martini instead of a wet flounder, come the end of a long day.”

She also extended the genre, making it not simply a compilation of recipes but a witty exploration of the zeitgeist.

That said, I’m off to make Stayabed Stew ( p15) – “for those days when you’re en negligé, en bed, with a murder story and a box of chocolates”.

Share this: