Winners, they say, write history. As the heroes of their own narratives, winners are wont to pick and choose information that supports their worldview and flatters their egos. As their stories are told and retold over generations, the narratives change and expand. Heroes are added. Locations are adjusted. How does the historian know what’s true?

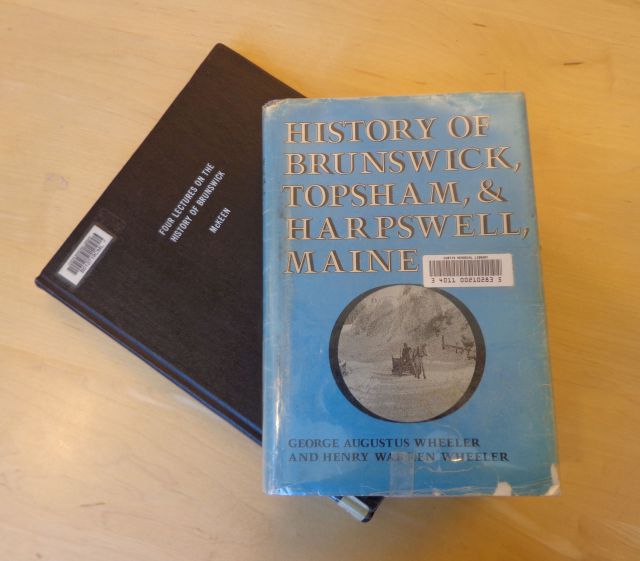

Historians compare conflicting information from various sources within the context of the era in which they were written, while considering the veracity and intent of those sources. Much like the winners, historians sometimes pick and choose information to support a point of view or to smooth the narrative flow. In the fall and winter of 1845-46, Brunswick historian John McKeen gave four lectures on Brunswick’s past (McKeen). Then George and Henry Wheeler used some of this information, combined with stories from local families and their own research, in their own 1878 history of the region (Wheelers’). These two works were my introduction to Brunswick history, but I’ve come to learn that sometimes they conflict with one another or with other sources.

Well, dear Reader, this is your chance to decide what’s true. I’ve included three “facts” from my Love Well, Love War series, along with my sources. Which “fact” will you choose to believe?

Gov. William Dummer courtesy Wikipedia. Public domain. Accessed June 17, 2017.

WHOSE WAR WAS IT?

The 1722-1725 war between British colonials and the combined Wabanaki-Franco forces is often known as the Three Years War. The Wheeler brothers referred to it as Lovewell’s War after New Hampshire militia leader Capt. John Lovewell. Wikipedia lists other names, as well:

- Dummer’s War after Lt. Gov. of Massachusetts William Dummer, leader of New England military forces;

- Father Rales’ War after the Jesuit missionary at Norridgewock;

- Greylock’s War for the Waranoak chief who led the Native forces in western New England;

- Anglo-Abenaki War after the British and the Abenaki tribe (one of the Eastern Wabanaki tribes)

- Wabanaki-New England War of 1722-1725 after the Eastern combined tribes and British colonists.

Feel free to choose the name you think best; I chose to use Lovewell’s War for two reasons. First of all, I liked the potential word play of “Love” and “War.” Secondly, Lovewell’s enthusiastic adoption of scalping his dead enemies for bounty seemed to reflect my British ancestors’ sense of entitlement to Native lands, superiority over the “savages,” and disregard for human life other than their own.

1790 Census, Brunswick and Harpswell, Maine. Ancestry.com.

WHICH SAMUEL EATON CARRIED A LETTER TO WHICH HARMON?

Wheelers’ states that Samuel Eaton Jr carried a letter requesting reinforcements from Capt. Gyles at Fort George to Col. John Harmon at Georgetown (Arrowsic Island). William Cutter in Genealogical and Personal Memoirs…Vol. 4. claimed the father, Samuel Sr, was the currier. Both sources agreed that Moses was the letter carrier’s brother.

Two lists of soldiers and early settlers in Wheelers’ offer more information. They show a Sgt. Samuel Eaton in Capt. Gyles’ company in 1723-24 who was promoted to lieutenant in 1724. Then a 1727 list of soldiers in Capt. Woodside’s company records the service of both Lt. Samuel Eaton and Sentinel Samuel Eaton. Finally, the early settlers of Brunswick include Lt. Samuel Eaton, apparently already here in 1717.

If the lieutenant and sentinel were father and son, it would seem that Sr made the arduous journey over land and sea. That is, if the Moses who was killed by Native warriors was Sr’s brother and not his son.

Have you decided between Sr or Jr? Either way, we might take comfort in knowing that the Eaton family all over the United States continues even today to name their boys Samuel and Moses.

Unfortunately for us, Wheelers’ reference to Col. John Harmon as the letter’s recipient is also problematic. That’s because brothers John (1680-1754) and Johnson (c1676-1751) Harmon were both military officers during Lovewell’s War, John as lieutenant and Johnson as captain. This means neither Harmon was a colonel at Arrowsic. Could it be that Col. Thomas Westbrook was the actual leader Capt. Gyles was contacting?

As an aside, researching brothers John and Johnson Harmon can be confusing because of their similar names. Johnson, the elder of the two, was given his mother Deborah’s maiden name. John was named after his father.

Mason’s Rock in center of photo. Image by Barbara A. Desmarais, May 9, 2017.

WHAT HAPPENED AT MASON’S ROCK?

Did Samuel Mason die at the hands of the Wabanki, at Mason’s Rock near the Brunswick shore of the Androscoggin River? Or was he rescued from drowning there? The source for both alternatives is Wheelers’.

Samuel Mason is listed in Wheelers’ Appendix 1 as having settled on lot 10 in Brunswick about 1717. The list states that he lived there less than three years, so he forfeited his lot. I researched his genealogy and found two Samuel Masons born in Massachusetts in the right timeframe. Family trees on Ancestry.com show Samuel, son of Lt. John and Elizabeth (Hammond) Mason, was born in Newton in 1688 and died in 1689, so he can’t be our man. Ancestry.com also listed the birth of Samuel, son of John and Sarah Mason, in Boston in 1689. I’ve found no further documentation for him, though there were Samuel Masons of the right age in Connecticut and Pennsylvania. I also looked through York County deeds for a pre-1753 Mason deed, to no avail. It’s possible Samuel moved, but it’s just as likely he died at Mason’s Rock. You choose!

If you’d like to see Samuel Mason’s rock, it’s clearly visible from the unimproved boat launch on Water St. in Brunswick. Just don’t mistake it for a nearby rock of similar size that’s closer to shore and only visible at low tide.

So, dear Reader, did you choose to remember Lovewell’s War or Greylock’s? Did you untangle the Eaton men? Did you save Samuel Mason at a rock in the Androscoggin River? What story about winners and losers did you choose to tell?

Next Blog: Winners and Losers

Sources:

- Ancestry.com, vital records, family histories, family trees, and databases.

- Desmarais, Barbara A., Image of McKeen and Wheelers’ taken at Curtis Memorial Library, Brunswick, Maine, June 15, 2017.

- Harmon, A. C. (Artemas Canfield), The Harmon genealogy, comprising all branches in New England. Gibson Bros., Inc., Washington, DC. 1920. New York Public Library, Call no. b5246557. https://archive.org/details/harmongenealogyc00harm. Accessed May, 2017.

- McKeen, John. Four Lectures on the History of Brunswick. Brunswick, Curtis Memorial Library, 1985. Call No. 974-191.

- Millard, James P., Abenaki Indian Chief Grey Lock. http://www.historiclakes.org/people/Greylock.html. Accessed June 13, 2017.

- Sylvester, Herbert Milton. Indian Wars of New England, Volume 3.Heritage Books, Inc., October 6, 2010. ISBN-10: 0788410792, ISBN-13: 978-0788410796. https://books.google.com/. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Wheeler, George Augustus Wheeler, MD. And Henry Warren Wheeler. History of Brunswick, Topsham, and Harpswell, Maine. Alfred Mudge & Son, Printers, Boston, Mass., 1878. http://community.curtislibrary.com/CML/wheeler/index.html, accessed April 17, 2017.

- Wikipedia. Dummer’s War. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dummer%27s_War. Updated December 17, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2017.

(c) Copyright 2017, Barbara A. Desmarais

Advertisements Share this:

- Share