Director: Richard Linklater

2014

I am neither a Richard Linklater fan nor an Ethan Hawke fan, as some of you may remember from my blog on Before Midnight (2013), and unfortunately for me they are one of those frequent collaborative pairings that you often find in Hollywood.

It’s fairly safe to say that I approached Boyhood with some already preconceived notions based on my previous experiences with the Linklater/Hawke pairing so I wasn’t really expecting much. Then there was my additional issue with films that seem to attract an annoying level of hype and praise before they even hit the cinemas in their general release (like Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens but more on that at a later date!) – so rarely do these types of film actually live up to the hype that I have learnt to temper my expectations. I guess this is in part why I avoid reviews as much as possible. Ironic I know, given that I am in the very process of doing exactly that and writing a review.

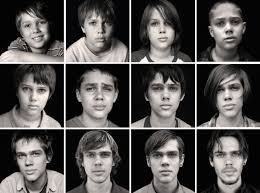

With Boyhood my reluctance to watch the film was not just the inordinate amount of hype surrounding the film, or the unfavourable pairing (at least in my eyes) but also the very concept of the film. Growing up is a hard thing to do in the first place without the added pressure of doing it on camera … and let’s face it Hollywood doesn’t have the best track record of looking after it’s young stars now does it? So to me the idea of filming someone going through what could arguably be the most awkward period of their life, over a prolonged period, seems massively self-indulgent on Linklater’s part.

“The actors age before us, though it is the evolution of Ellar Coltrane (who plays the boy, Mason) and Lorelei Linklater (the director’s daughter, playing Mason’s sister) that has the most resonance.” (931, Mick McAloon, 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

While it is kind of fascinating to watch Ellar Coltrane grow up I was never entirely comfortable with the film and couldn’t quite ignore my feeling that it’s somewhat exploitative. There doesn’t actually appear to be that much of a narrative but rather relies on the gimmick of watching the cast age across the period of 12 years. It’s a massive undertaking on all parts, which I do definitely recognise, but in the main just ends up strengthening my view that the film is much more about Linklater’s overweening arrogance. In recognising Linklater’s achievement I am never the less left with a faint sense of voyeurism that never really sat very well with me.

While it is kind of fascinating to watch Ellar Coltrane grow up I was never entirely comfortable with the film and couldn’t quite ignore my feeling that it’s somewhat exploitative. There doesn’t actually appear to be that much of a narrative but rather relies on the gimmick of watching the cast age across the period of 12 years. It’s a massive undertaking on all parts, which I do definitely recognise, but in the main just ends up strengthening my view that the film is much more about Linklater’s overweening arrogance. In recognising Linklater’s achievement I am never the less left with a faint sense of voyeurism that never really sat very well with me.

Advertisements Share this: