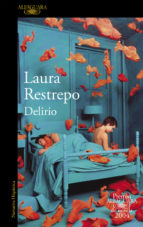

This brilliant and moving novel, set in Colombia,  begins when Aquilar returns from a short trip to find that his wife has gone crazy: he left her decorating their apartment and returned to find her in a random hotel room, deranged and unable to explain what had happened in his absence. The events leading up to this are slowly unravelled by several narrators, the most important of which are Aquilar and a man named Midas McAlistair, often in the form of a sort of dialogue with Agustina with frequent changes of pronoun and perspective which both disconcerts and adds to the feeling of destabilisation one experiences when reading this text.

begins when Aquilar returns from a short trip to find that his wife has gone crazy: he left her decorating their apartment and returned to find her in a random hotel room, deranged and unable to explain what had happened in his absence. The events leading up to this are slowly unravelled by several narrators, the most important of which are Aquilar and a man named Midas McAlistair, often in the form of a sort of dialogue with Agustina with frequent changes of pronoun and perspective which both disconcerts and adds to the feeling of destabilisation one experiences when reading this text.

Aquilar’s narrative takes us back to his meeting with Agustina only a few years previously and fills in her family background. Coming from a wealthy Colombian family her childhood was dominated by a powerful and macho father whose sense of masculinity is affronted by the sensitivity and gentleness of his second son, Bichi. Close as she is to her brother, Agustina’s childhood is characterised by anxiety as she second guesses her father’s cruel and violent outbursts and tries to protect her younger brother from them. Her marriage to the impoverished academic Aquilar is barely acknowledged by her family and we are shown an unattractive middle class with shallow materialistic values, entrenched gender roles and a family life riddled with concealment and lies.

Through the narrative of Midas McAlistair we learn more about the provenance of the family wealth: Agustina’s father and older brother are involved with a whole money laundering business run by Pablo Escobar and from the very beginning we are left in no doubt as to the cost of this in terms of violence and human life. The relationship between McAlistair and Agustina is at first unclear but we later learn that he is a school friend of her older brother, was infatuated with her from afar and that this develops later into some kind of relationship. McAlistair comes from a humbler background than Agustina’s family and in the condescension and bullying he experiences at the prestigious Liceo Masculino we see further examples of the class consciousness and snobbery of the middle classes. Yet there’s the suggestion that their hegemony is both recent and precarious. McAlistair is aware as a boy that even at the posh boys’ houses they ate the same basic comfort food and growing up he sees that the wealthy are no good at managing their estates- they lack business sense and it’s people from his class background who are better at running the show.

The precarity of wealth and status is illustrated in the wonderful saying ‘Bisabuelo arriero, abuelo hacendado, hijo rentista y nieto pordiosero’- Greatgrandfather muleteer, grandfather landowner, son tenant and grandson beggar. The rapid change in fortunes and status in Colombian society can also be seen in the story of Agustina’s grandfather, Paulinus which makes up the third narrative strand. He is a musician and from Germany. Arriving in Colombia he married Blanca and was content to swap his Bach and Beethoven for Colombian vallenatos. However when we meet him in the novel he is beginning to suffer from hallucinations and obsessions- and this account of mental fragmentation and breakdown so carefully managed by his wife Blanca is movingly told. We are led at first to wonder whether his mental disintegration is a response to living and working in a different language and culture,or whether it is a genetic predisposition, passed on to his granddaughter Agustina. But then towards the end of the novel some elements of his childhood are revealed which suggest childhood trauma may have played a part.

What we also see in Paulinus’ story is the importance accorded to boys over girls in the family, the masculine over the feminine. Paulinus and Blanca have accepted into the bosom of their family a young man, Farax, who turns out to be a talented musician and whom they dote on, while their own daughters are rather shadowy figures in the background at this stage of the story. This mirrors the centre stage accorded to Joaco, Agustina’s older Alpha male brother, in the family and the brutality and rejection meted out to Bichi because he doesn’t conform to the masculine stereotype. The culmination of this drive to assert masculinity comes when one of the money laundering gang commandeers a sadistic floor show in an attempt to achieve sexual arousal-he’s paralysed from the waist downwards after a bomb attack- with tragic consequences.

This is a compelling book which operates on several levels. We are driven to discover what has happened to Agustina, the source of her breakdown, by the carefully controlled slow reveal of elements of her family background which works like a detective story to hold our attention. Aspects of contemporary Colombia are explored which would induce a permanent state of anxiety in most people. It is not just the involvement of Agustina’s family which we are shown but violence as a fact of life in the casualness with which people accept roads being controlled by paramilitaries or guerrilla forces at certain types of day, the references to a favourite cafe as the one where the owner was decapitated. At the same time towards the end I felt a more diffuse sense of unease as the narrators shift their tone. A tense scene with Midas and Agustina reveals his underlying nastiness and real power and even the hitherto good guy Aquilar seems to be displaying some greedy if not exploitative attitudes towards the women in his life.

For me, the hope for a different future lies with the character of Bichi- what happens in the last crucial scene before he walks out on his family. And the open ending when the family are waiting for his return. You will have to read it to learn more and to appreciate the tour de force which is this fantastic novel about madness in modern Colombia.

Advertisements Share this: