by Karen Williams Follow @redrustin

Uganda’s government recently announced that it has ended the manhunt for the leader of the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army, Joseph Kony. At its height, the group wreaked havoc in northern Uganda, before dispersing across central Africa in recent years. It continues to attack civilians in the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Despite an international arrest warrant for the LRA’s leadership, only one LRA member is currently standing trial at the International Criminal Court. He was, ironically, kidnapped as a child by the LRA. Karen Williams looks at his life.Dominic Ongwen is the youngest person indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity in an international court. Now believed to be in his early 40s, he went on trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, the Netherlands, on 6 December 2016. He faces an indictment of 70 charges, thereby making him the accused charged with the most number of grievous international crimes. In addition, he is the first former child soldier who has been charged by the ICC[1].

I have known Dominic Ongwen’s name for nearly fifteen years. It has been a shadow walking alongside me, since the early days when I went to northern Uganda to see the effects of the civil war that was raging at that time.

ICC Chief Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda

ICC Chief Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda

ICC Chief Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, said that he was a “murderer and a rapist”. The charges against him are related to war crimes and crimes against humanity, and include:

War crimes: attack against the civilian population; murder and attempted murder; rape; sexual slavery; torture; cruel treatment; outrages upon personal dignity; destruction of property; pillaging; the conscription and use of children under the age of 15 to participate actively in hostilities;

Crimes against humanity: murder and attempted murder; torture; sexual slavery; rape; enslavement; forced marriage as an inhumane act; persecution; and other inhumane acts.[2]

According to the ICC, the charges relate largely to Ongwen’s time as the commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army’s (LRA) Sinia Brigade.

“The confirmed charges concern crimes against humanity and war crimes allegedly committed during attacks against the Pajule IDP (October 2003), Odek IDP (April 2004) Lukodi IDP (May 2004) and Abok IDP camps (June 2004), as well as sexual and gender-based crimes directly and indirectly committed by Dominic Ongwen and crimes of conscription and use in hostilities of children under the age of 15 allegedly committed in northern Uganda between 1 July 2002 and 31 December 2005.”[3]

It is exactly in Dominic’s role as a commander that his story gains significance. The Enough Project has written that in addition to his command of the Sinia Brigade, he was also elevated to the LRA’s high command (known as the Control Altar)[4].

The war in northern Uganda was known to only a few interested parties. Outside of Uganda, and even within the country, it was little spoken of. But it was not a forgotten conflict: it had never been a priority for Ugandan, African or international attention. It went on for more than two decades, invisible to all but its victims.

At that time, few people made it to the main northern town of Gulu: even the Ugandan soldiers tried to avoid the posting. The civil war waged by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) was concentrated in the country’s north. For Ugandans from outside of the area, the north was a foreign land, the war waged by people they saw as largely animist and culturally different to the rest of the Uganda.

Journalist Els De Temmerman describes the boundary between northern Uganda and the rest of the country:

The Nile drew a natural border between the two regions. When one crossed Karuma bridge from the south, a different world emerged, a world of destruction and terror and paralysing fear.[5]

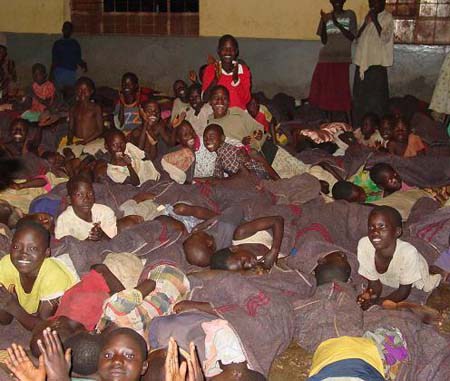

The children weren’t only killing and terrorising the local population (whom they were part of): the children were also the young ones hiding, dealing with being torture survivors and rebuilding lives. If you wanted to know how bad the abductions by the LRA was at a particular time, all you had to do was wait for late afternoon to see the number of children who would trek into town from Pabbo displacement camp, to sleep overnight in Gulu town rather than risk abduction in their homes.

Before his abduction, Dominic Ongwen was one of these children. And for so many years, Dominic was to me, the archetype of the broken, splintered child whom I encountered not only when I was in northern Uganda, but again and again in Sierra Leone and Liberia, Burma and Afghanistan. A broken, violated child; and allegedly a terrifying mass murderer.

Known as the White Ant throughout his time as an LRA figure, Ongwen was notorious and feared. Before that, he was a little boy, a northern son who was brutalised by the LRA war.

A familiarity with key figures in the LRA was not uncommon. They were homeboys, and it was not unusual for me to shoot the breeze with the region’s numerous Catholic[6] nuns and priests, who would tell me anecdotes of when they knew LRA leader Joseph Kony (an altar boy) or any of the other big names.

Dominic Ongwen in the LRA

Dominic Ongwen in the LRA

Photos of the LRA were rare, but there was one in circulation of Dominic: his baby face looking at the camera, the light at just the right angle to make the plane of his features clear. He is wearing a beret, which looks like a child’s play prop against his battle fatigues. His baby-dreads stick out from under the beret. He could be your next-door neighbour, or your brother’s irritating friend. I had heard of the White Ant and his atrocities for years, and had lived in fear when there were rumours that he was spotted in the area. Yet looking at those photos I immediately thought, That’s him? That young guy? That’s him?

His personal story was much spoken about in Gulu, because as somebody who was simultaneously a victim and perpetrator, Dominic came into the LRA as an abducted child. The popular talk in northern Uganda alleged that he was kidnapped along with his brother when he was ten years old.

Reading through recent media reports filed since his surrender in the Central African Republic (CAR), what I thought I knew about this life story took a turn, and a sickeningly familiar one.

Reporters had interviewed a woman they identified as Dominic’s sister. The indictment of her brother brought attention to her.

There was a stomach-churning element to his sister’s story. It was a familiar feeling, particularly after the years of meeting girls who had been captured by the LRA. She was identified as a “wife” of LRA leader Joseph Kony. The news reports also said that she had had a number of children with the LRA leader.

Could the brother that I kept hearing about in northern Uganda, actually have been a sister who was abducted with him?

I was always interested in Dominic’s sibling who was abducted along with him, because I knew from having spoken to freed captives just what was in store for them. For me it was one of the key ways to explain how and why he had to rise up in the LRA ranks, in addition to simply trying to stay alive. I also knew that the only way to get a measure of protection within the LRA ranks as a child was to exert maximum brutality on other children. The resonance to Dominic’s life was clear to me: one way he could ensure his survival was to distinguish himself to the LRA commanders in the only way that they valued.

This offered protection from the brutalisation within the LRA and allowed captives to move up the ranks of the group: in turn, you brutalised others and issued orders. And the surest way to “prove” that you were worthy of leadership within the LRA was to exact brutality upon the young foot soldiers.

Children sleeping in the towns of northern Uganda. They were known as “night commuters” (Source: WikiCommons)

Children sleeping in the towns of northern Uganda. They were known as “night commuters” (Source: WikiCommons)

In Gulu, a number of people through the years told me about a practice of the LRA to have a pile of sticks and to beat selected children in their ranks until all of the sticks were used or broken. Group beatings by fellow captives was also routine.

My belief that Dominic had a brother kidnapped with him made the urgency to survive much more important. This was now given greater urgency with this information of his sister, most likely sexually enslaved by Kony.

I’d heard similar stories of girls’ captivity often enough when I was in northern Uganda. I heard it in all that the girl captives left unsaid, and in all that for the rest of their lives would always be present and unsayable.

There were no “wives” in the sexual enslavement. If Dominic moved through the LRA ranks to protect himself in the only way possible, through brutality, what were the dynamics of having a sibling – and a girl – within the movement?

In an even more horrific reflection of what the LRA did to children’s lives, Ugandan media reported that the ICC has identified seven young women who were sexually enslaved and forcibly partnered with Dominic and bore him children conceived through rape. They will reportedly testify against him.[7]

Violence within LRA ranks Dominic Ongwen during his time in the LRA

Dominic Ongwen during his time in the LRA

The focus of LRA brutality concerns mainly the violence it perpetrated against civilian populations. Less known is the degree of daily brutality within its own ranks. Violence is a common practice within the LRA, designed to facilitate the brutalisation, torture, indoctrination and ultimately, psychic breaking of child abductees. Beatings are usually perpetrated by groups of abductees who are forced to beat somebody chosen for punishment.

When siblings, best friends or parents were abducted with their children, they were singled out for torture and indoctrination. There was a discernible pattern. The brutality would happen from the moment of abduction, so that by the time that the children reached the LRA camps, they were already pliant. Yet, even with the scale of violence within captivity and the threat of death to children and their families back home, many children successfully escaped when an opportunity presented itself.

Commonly, anybody showing a filial relationship or bond would be targeted, usually soon after the abduction. The abducted children would be tasked to beat the adult to death or kill them by other means. It was important for the LRA that any of the abducted children who were related to the adult had to take the lead in the killings. Often body parts, particularly hearts would be boiled, and each of the children forced to eat a piece.

Similarly, any bond between the children had to be broken. If there were siblings, or close friends, one would be targeted, with one friend forced to murder the other and the children forced to eat a piece of the body. It was a policy to ensure that, for the children, there would be no going back.

Resistance or attempting to escape could easily result in being killed in the LRA. Therefore, for siblings such as Dominic and his sister to have survived for that long in the LRA camps is itself notable. That both were embedded in the top structures adds a particular horror to the story.

LRA before ICC

Ongwen is the first LRA commander, as well as the first LRA member, to appear before the ICC, out of an original indictment of five senior LRA members. The ICC opened the investigation against the rebel movement in 2004 after Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni asked the ICC to start an investigation.

The primary accused in the ICC Uganda case, LRA founder and leader, Joseph Kony, is still at large. The co-accused, Raska Lukwiya and Okot Odhiambo, have died.[8]

LRA founder and leader, Joseph Kony (centre) in white suit. Kony’s former deputy, Vincent Otti, is on his right in the tan suit. (Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica)

LRA founder and leader, Joseph Kony (centre) in white suit. Kony’s former deputy, Vincent Otti, is on his right in the tan suit. (Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica)

The case against Kony’s deputy, Vincent Otti, is still open, even though he is widely reported to have died in 2007. Otti’s killing, apparently as part of an LRA power struggle, happened during one of the times that I was living in Gulu.

The weekend after his reported murder, there were further lurid rumours of Kony having sent Otti’s genitals to his traditional medicine man in Gulu, to cook and to turn into a potion. The LRA refused to publicly confirm or deny Otti’s demise. He was the second-in-command of the LRA during a time when they were in negotiations with the Ugandan government. The talks were mediated by Southern Sudanese politician, Riek Machar, and in 2008 Machar supported the reports that Otti had died,[9] after he said that the LRA had confirmed the death to him.

LRA background

After the collapse of the peace talks with the Ugandan government, the LRA moved its bases from Sudan[10]. Instead of Kampala wiping out the LRA, the character of the war changed and the group morphed in response to the renewed military pressure. The LRA abandoned its base in then-southern Sudan[11] and became a regional menace, spreading terror, abductions and sexual violence to regional countries that were themselves becoming increasingly unstable. This included the then-southern Sudan, the Central African Republic (as the country was veering towards its current civil war) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Even within its new locations, Dominic Ongwen’s name soon became notorious:

After LRA forces left northern Uganda in 2005 and 2006, troops under Ongwen’s command repeatedly terrorized communities in Congo’s Haut Uele and Bas Uele districts. His troops were responsible for some of the LRA’s most vicious attacks in the following years, including the Makombo massacre in 2009, one of the worst during the LRA’s long, brutal history. Troops under Ongwen’s command killed at least 345 civilians and abducted another 250, including at least 80 children, during a four-day rampage in the Makombo area of northeastern Congo.[12]

According to a HRW report:

LRA forces attacked at least 10 villages, capturing, killing, and abducting hundreds of civilians, including women and children. The vast majority of those killed were adult men, whom LRA combatants first tied up and then hacked to death with machetes or crushed their skulls with axes and heavy wooden sticks. The dead include at least 13 women and 23 children, the youngest a 3-year-old girl who was burned to death. LRA combatants tied some of the victims to trees before crushing their skulls with axes.

The LRA also killed those they abducted who walked too slowly or tried to escape. Family members and local authorities later found bodies all along the LRA’s 105-kilometer journey through the Makombo area and the small town of Tapili. Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that for days and weeks after the attack, this vast area was filled with the “stench of death.”

Children and adults who managed to escape provided similar accounts of the group’s extreme brutality. Many of the children captured by the LRA were forced to kill other children who had disobeyed the LRA’s rules. In numerous cases documented by Human Rights Watch, children were ordered to surround the victim in a circle and take turns beating the child on the head with a large wooden stick until the child died.[13]

The Ugandan government recently announced that it is ending its manhunt for LRA leader, Joseph Kony. With Dominic Ongwen’s trial currently underway at the ICC, it is a bitter irony that the only person standing trial for the LRA’s crimes is the group’s most renowned victim.

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Footnotes

[1] Information confirmed in written communication with ICC

[2] https://www.icc-cpi.int/uganda/ongwen/Documents/OngwenEng.pdf

[3] https://www.icc-cpi.int/Pages/item.aspx?name=pr1216

[4] http://www.enoughproject.org/files/publications/wanted_fbi.pdf

[5] De Temmerman, E. Aboke Girls: Children Abducted in Northern Uganda, Fountain Publishers, Kampala 2002, p.39

[6] The reference to Catholicism is important: in Uganda, the churches reflect a political divide. The Anglican church has often been associated with the government establishment, with the Catholic church often acting as an opposition. This has been strengthened by the strong presence of the Catholics in northern Uganda, where, during the war years, it was not unusual for the government to hint that at times the Catholics were siding with the LRA, or hinting that they occasionally hid LRA fighters. This divide plays out significantly in Catholic pronouncements on the LRA and northern war, and influences political tussles over who “speaks” for the north.

[7] https://ugandaradionetwork.com/story/dominic-ongwens-two-day-opening-trial-ends-at-icc

(first accessed 12 April 2017)

[8] https://www.icc-cpi.int/uganda/kony

[9] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7204278.stm

[10] The LRA were based in areas that bordered northern Uganda, namely southern Sudan, which would become the Republic of South Sudan. The Sudanese government under Omar al-Bashir were the main funder of the LRA.

[11] The area would become the Republic of South Sudan in 2011.

[12] https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/12/05/questions-and-answers-lra-commander-dominic-ongwen-and-icc (First accessed 22 March 2017)

[13] https://www.hrw.org/news/2010/03/28/dr-congo-lords-resistance-army-rampage-kills-321 (first accessed 22 March 2017)

References

Aboke Girls: Children Abducted in Northern Uganda – Els De Temmerman, Fountain Publishers, 2002

https://www.icc-cpi.int/uganda/ongwen/Documents/OngwenEng.pdf

https://www.icc-cpi.int/Pages/item.aspx?name=pr1216

http://www.enoughproject.org/files/publications/wanted_fbi.pdf

https://ugandaradionetwork.com/story/dominic-ongwens-two-day-opening-trial-ends-at-icc (first accessed 12 April 2017)

https://www.icc-cpi.int/uganda/kony

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7204278.stm

https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/12/05/questions-and-answers-lra-commander-dominic-ongwen-and-icc (First accessed 22 March 2017)

https://www.hrw.org/news/2010/03/28/dr-congo-lords-resistance-army-rampage-kills-321 (first accessed 22 March 2017)

Email communication with ICC

Karen Williams works in media and human rights across Africa and Asia. She was part of the democratic gay rights movement that fought against apartheid in South Africa. She has worked in conflict areas and civil wars across the world and has written extensively on the position of women as victims and perpetrators in the west African and northern Ugandan civil wars.

If you enjoyed reading this article, help us continue to provide more! Media Diversified is 100% reader-funded – you can subscribe for as little as £5 per month here or support us via Patreon here

Share this: