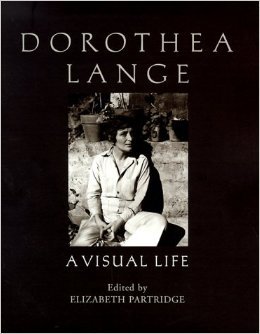

Dorothea Lange: A Visual Life, edited by Elizabeth Partridge, has a substantial amount of text, but before seeing the documentary film (of the same title) directed by Meg Partridge (and a lively Q&A session with the two of them and their father Rondal Partridge, who had been Lange’s assistant during the Great Depression expeditions that produced her most famous image(s), I settled down to read the essays in the book.

The ones I found most engaging were those by persons who knew Lange personally —the editor who was a quasi-member of the family, Lange’s son David Dixon, former University of California president Clark Kerr, and photographer Anselm Adams who worked with or in parallel with Lange on several projects, including photographing the Manzanar, California concentration camp for Japanese Americans removed to the east side of the Sierra Nevadas by an order from Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

That Lange drove herself hard is reported both by those who knew her well and by the women’s studies scholars (Linda Morris, Sally Stein) who wrote from a greater analytic distance from Lange (though, IMO, less critically). She was also a very demanding mother and contract employee. Even more than Dixon, Partridge reports pained incomprehension by the boys, who were sent off to boarding school so that their father, painter Maynard Dixon, and mother (Lange) could focus on their work (/career/art). Morris particularly focuses on Lange’s ambivalence about the role of mother: photographing women who existed entirely in the domestic sphere in which she refused to be encased, but also could not (she felt) altogether abandon. Morris quotes Christina Gardner, another former Lange assistant, saying that “she knew the importance of maternity was not a very maternal person.” Moreover, she pressed her work ethic on her sons (more than on her quasi-granddaughters, Meg and Elizabeth Partridge).

Lange was, Morris writes, “opinionated, impatient, and willful,” but I am somewhat surprised that Morris does not put “difficult woman” in scare quotes, since “difficult woman” seems to me a highly suspect label, one with a much lower threshhold than “difficult man,” and one invoked disproportionately to justify not supporting women working in predominantly male professions. Lange’s first husband, the father of her sons, for instance, sounds to me as not just “difficult” but outright “ornery” as well as being more egocentric.

I don’t at all mean to suggest that Morris is lacking in sympathy for the difficulties Lange had trying to make it in very male worlds during very hard times (the Great Depression). Her essay is an excellent introduction to Lange’s work and sense of vocation, and I especially appreciated the technical explanation of why most of Lange’s photos of people in the field (AKA “real world”) look up (literally) rather than down (though her second most famous photo, of a San Francisco breadline in 1932 DOES look down). The Rolleiflex camera she preferred was at waist level rather than eye level (as 35mm cameras were).

(I think Lange’s secon most-famous image (after “Oakie Madonna” reproduced in my previous review): 1 933 breadline in San Francisco)

The longest essay in the book is Sally Stein’s “Peculiar Grace” on “the testimony of the body” in Lange’s photographs. Stein seems to me to go out farther on limbs of speculation about motivation than any of the other authors of essays in the book. Her theses about how the effects of childhood polio (contracted when Lange was seven) and adult illness (of the digestive system, culminating in the fatal cancer of the esophagus) affected what she photographed (notably, a lot of shots of feet and legs) are provocative. (This argument is undermined, perhaps unconsciously, by Elizabeth Partridge’s selection of Lange photographs, in which hands are very, very prominent, much more than feet are.)

Stein suggests that other photographers on the payroll of New Deal organizations (including, the War Relocation Authority, which staffed concentration camps with New Deal officials) censored themselves, while Lange resisted and insisted on documenting unpleasant realities (barbed wire and guards, for instance, in the Manzanar photos). This seems almost certainly to be true.

I can imagine arguments being made against Stein’s interpretation that Lange’s photographs “de-emphasized the social and environmental context in order to focus on the body alone as a site of social formation and deformation,” though I think there is something valid in it. He suggestion (which she hedges as “arguable”) that Lange’s modus operandi “appeared to universalize, perhaps inadvertently, the nature of alienation by embodying it in rather general terms” surely would be rejected by Lange’s many admirers — especially that “general terms.” It seems to me that a more plausible argument could be made that Lange’s close-up photographs were so specific as to open reading (of the images) as psychological maladies rather than sociopolitically produced dilemmas (the process of mechanizing and increasing the scale of American agriculture was one that Paul Taylor was particularly interested in and that Dorothea Lange extensively documented).

Stein sometimes writes jargonistically (as no one else in the volume does) and along with providing arguments that I find stimulating even if unpersuasive, there is one outright anachronism in Stein’s chapter. Stein interprets Lange’s use of the male pronoun for the photographer as evidence of a failure to be able to conceive females in the profession. If someone now wrote that way, I would accept the interpretation, but that “he” was general/generic was the grammar of the English language during the 1930s, not a conscious pragmatic choice. “He or she,” “s/he,” etc. were not in use. The most that can be said is that Lange did not invent them then. Articulate a speaker/writer as she was, would anyone expect her to have made that linguistic innovation?

There are Lange photographs (including a few of her by Rondal Partridge) throughout the book and a chronological set of 56 Lange photographs with quotations from the 1960-61 interviews (also used extensively in the documentary film “A Visual Life”) of Lange (in the Regional Oral History Archive of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley).

(1936 photo of Lange at work shot by her husband, Paul Taylor)

I find Lange’s photographs from Egypt particularly striking. Although she was accompanying Paul Taylor, these do not seem to be part of the kind of documentation project she had done in Mississippi, Utah, the California forced resettlement of Japanese Americans, an Alameda County Public Defender, and the famous Dust Bowl migrants’ work. I don’t think that art(istry) and documentation are incompatible and I think that all of Lange’s photographs are both, but these seem to me to be particularly striking pieces of photographic art.

I think that many will find Stein’s chapter heavy going. I found much of interest in it, but even skipping it, there is a wealth of verbal insight about Lange and Lange’s photography in the book, which I highly recommend to those interested in the history of photography, New Deal (self-representations), the shameful wartime treatment of Japanese Americans, and/or the extra hurdles female artists — and other professionals — had to overcome to do “men’s work”/create art/document history as it unfolded (and, of course, those interested in Lange and/or her two husbands, Maynard Dixon and Paul Taylor).

— — —

Elizabeth Partridge is also the author/compiler of Restless Spirit: The Life and Work of Dorothea Lange (2001), This Land Was Made for You and Me: The Life and Songs of Woody Guthrie (2002) and of Quizzical Eye: The Photography of Rondal Partridge (2002), along with much historical fiction and many children’s books,

Photographing people not posing for her, Lange used a wider, faster aperture than that which was taken for the northern California (all-male) photographers Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, W. S. Van Dyk, et al., f64. In his interview included in the book Adams says that they should have made the effort to find out what she was doing (not without noting that what she was doing during the late-1920s was high-society photographic portraits, not the documentation of the displaced she undertook during the 1930s and early 40s).

©2008, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

Advertisements Share this: