He said it would hurt like hell, and he was right.

He said it would hurt like hell, and he was right.

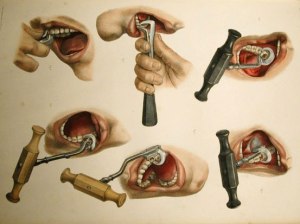

I knew when I recognized my own voice that those clichéd descriptions of people yelping in the dentist’s chair are based in reality. Beyond the instruments in my mouth and the hands wielding them, I could see my legs and feet in agitated motion, as if trying to run away: away from the heavy pressure, the deep pinch of the needle, the sharp edge of the tiny blade peeling gum from tooth.

Pain is a clarifying experience, and a sobering one, too. Before its power, every petty neurosis and trivial complaint evaporates; you want only for it to stop, and your life will be made good and whole. At the same time you realize just how much the body — the one to which you are unavoidably consigned — can hurt: If not this moment, some other. You see that this universal part of human experience can become singularly yours with stunning quickness.

For me, it took the form of a bum tooth that had been aching for several days, swelling my jaw line. After I awoke early yesterday with the addition of a fat lip, I drove to my dentist’s office to be there when it opened. Dr. Guerra quickly diagnosed a tooth that would need a root canal, but not before the infection causing the swelling was brought under control. So she called in a favor to an oral surgeon, and an hour later I was in his chair, bracing myself against the draining of the abscess, which commenced without the injection of a numbing agent because there is only so much available space in already swollen tissue.

I left his office with a drain stitched into my gum and a piece of bloody gauze protruding from my mouth, which either impressed or appalled the pharmacist to whom I handed the painkiller scripts shortly thereafter.

But my day wasn’t over: I went directly back to Dr. Guerra to have the tooth opened and prepped for the root canal, in an attempt to lessen the chance of the infection regaining a foothold. My body shook involuntarily in her chair: The small amount of numbing agent injected by the oral surgeon as he evacuated the infection had already worn off, and my usually low blood pressure was through the roof.

Dr. Guerra covered me with a blanket, then injected anesthetic into the traumatized gum as gently as she could. Then she waited, stroking my good cheek and speaking softly to me as if I was someone she loved, and not just her patient. She is not only a skilled practitioner, but deeply kind.

Ten long minutes later, the anesthesia had kicked in and my body had quit shuddering. Dr. Guerra did the work. And I went home with my painkillers, the worst being over, at least for now.

I had taken with me that morning How to Be Sick, a wise and courageous book by Toni Bernhard, a University of California law professor who became ill in 2001 and never got better. The source of her sickness — likely some pathogen she contracted on a flight to Paris — has never been identified, and a succession of doctors has been unable to treat what Bernhard came to call “the Parisian flu. ” The mysterious illness ended her career and severely curtailed her family and social life, often leaving her too weak to do anything but lie in bed.

Yet in applying Buddhist teachings and sharing her experience, Bernhard has made something gracious and transcendent of what might have been an embittering mystery. She has come to accept her continuing sickness and its associated losses as simply her share of the difficulties each of us will experience, in our way, if we live long enough. And she has come to understand that — no matter what hardships befall us — gratitude and even happiness are yet possible, if we can work with our confused and fearful minds.

I thought of that yesterday in the surgeon’s chair, in the iron grip of a kind of physical pain I had never experienced. My share this time, and in this form. And I think of it today, as I count the hours until the next megadose of ibuprofren and appreciate anew the soft sustenance of eggs and soup, oatmeal and yogurt.

Anything can happen at any time. That’s how teacher Joseph Goldstein expresses the core Buddhist teaching on impermanence. Health can become sickness before one knows it; pain can arise and explode with awesome force. But on the other side? A day out of bed after a day contained, or a few hours of counting through modest discomfort after squirming and trembling beneath the weight of radical pain.

It’s no less true in the emotional realm: Anything can happen at any time. Things go well, and then they don’t. The stars align and we feel suspended by grace; then we find ourselves shaken by a sudden tectonic shift in the ground we presumed was solid. Loss follows gain follows loss.

Bernhard opens her book with a quote from Zen Master Setcho Juken:

One, seven, three, five —

Nothing to rely on in this or any world;

Nighttime falls and the water is flooded with moonlight

Here in the Dragon’s jaws:

Many exquisite jewels

The jewels of Bernhard’s experience are evident in her shared understanding of how to work with a suffering mind when the “anything” you don’t want inevitably manifests. Mine are less heroic, though precious enough to me: a mind cleared, however briefly, of the detritus of small concerns, of minor complaints; a body exhausted but relaxed. I do not hurt, at least not nearly as bad as I did yesterday. From pain, perspective.

“Without the bitterest cold that penetrates to the very bone,” writes the Zen master Dgogen, “how can plum blossoms send forth their fragrance all over the universe?”

Advertisements Share this: