D is another good literary letter. D is for Dickens, Dumas, Doyle and Drabble. D is also, coincidentally, a good letter to describe where I spent my recent week’s holiday. D is for Devon, Dittisham, Dartmoor and Dozmary. The English South West; a medley of rolling hills, picturesque rivers, rugged coastline and wild moorland, all imbued with a sense of ancient mysticism born of a landscape that whispers of a time long before the motor car, before steam power, before the building of the great castles and the writing of the Doomsday Book, before the Conquest of the Normans and the coming of the Saxons. The landscape of the ancient kingdom of Dumnonia, the landscape of King Arthur; the seascape of pirates and wreckers and smugglers; the birthplace of the great sea captains Drake and Raleigh and Hawkins. D is a letter of riches in literature and inspires a rollcall of illustrious locations that are, in my view, greatly suited to the enjoyment of a good book. D is also for decisions, daftness and a degree of dismay, which rather sum up my efforts to honour this letter in my reading A-Z.

D should have been so easy. There are plenty of D authors, so choosing a new one was no hardship. I even had a recommendation: Lindsey Davis, whose mysteries set in ancient Rome I have been told are rather good. Ten days or so ago I sauntered with confidence into my local bookshop (I would use the word swagger to evoke the smugness with which I strode, but I fear I don’t have the gait of a swaggerer; more of a lurching waddle, perhaps) and found Davis’s first book sitting idly on the shelf. An easy capture. And yet I came unstuck. A quick glance along the shelves brought me to E.M. Delafield’s The Diary of a Provincial Lady, an amusing-looking book set in Devon in the 1920s. Knowing that I would soon be in Devon, and knowing nothing of the author, I thought the volume too good to pass up on.

In a welter of indecision I drifted to the till with both books, thinking that I could choose between them later. As is usual a conversation that can only be described as desultory (another solid D word) began with the shop assistant, which led to her recommending a recent publication that she thought might be of interest. Normally I smile politely and decline such things, but this book did sound somewhat interesting; after some mild coy demurral I admitted defeat and added it to my purchases. As luck would have it, the author was another D. Thus Helen Dunmore’s Birdcage Walk appeared to confuse the mix yet further.

There followed a debate as to which D I should take on holiday, and after a short reflection I plumped for Delafield’s work, simply for the location. Davis and Dunmore would await me at home for another day. Imagine then my dismay, my anguish, nay, my horror when on arrival in Devon I discovered that The Diary of a Provincial Lady is in fact a collection of four novellas rather than one single full-length work, a fact which neither the blurb nor the publisher’s introduction saw fit to mention. There I was, the owner of many a fine D, only to have in my immediate possession a volume that falls foul of my self-imposed rules. Naturally I was tempted to test the pliability of my own regulations, but if I could cheat at D just imagine what malefactions I would be committing once Q or X hove into view. No, duplicitousness just would not do.

I needed another D. Of course in the meantime I read the first novella of The Diary of a Provincial Lady – I’m not a callous barbarian, after all – and found that it captured some of the parochialism of English provincial life in the interwar years, and provided an amusing pastiche of the rural upper-class idyll. The eponymous lady diarises her trivial triumphs and disasters most assiduously, presenting a litany of awkward social calls, horticultural disasters, matrimonial mishaps, and family and village rivalries. I expected perhaps a few more mountains to be made out of minor rustic molehills, and a few more petty local disputes, but on the whole I thoroughly enjoyed Delafield’s work. I shall have to return to it anon, but sadly I could not count it in my A-Z challenge.

I am rather fortunate that Dartmouth – a small fishing, yachting and tourist town on the south Devon coast, perhaps most famous for the large Royal Naval college – boasts a couple of good bookshops, and within a day of discovering my error I had the opportunity to make it good. By now I very much liked the idea of reading something with a local flavour (if only I hadn’t already read Hound of the Baskervilles!) and stumbled on a rather elegant solution: Daphne Du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn. Now, the purists may argue as to whether Du Maurier is a D or M, but the fact that bookshops stock her under D is good enough for me. Purists may also argue that a book set in Cornwall is not really local for Devon, but the hop across the Tamar is short enough that I saw no reason to quibble.

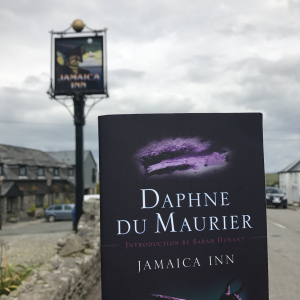

Jamaica Inn is the story of a young woman, Mary Yellan, who goes to live with her aunt and uncle in an inn in the middle of Bodmin Moor in Cornwall. Mary is perturbed by dark goings-on at the inn and wrestles with her conscience and loyalty to her aunt, all the while being unsure who among her (very few) new friends on the moor is to be trusted. It is a tale of greed and crime and passion in a setting spectacular for its bleakness and isolation. Best of all, Jamaica Inn is a real place and could be visited (relatively) easily in a day trip from our base in Devon. Du Maurier was apparently inspired to write the book after arriving at the inn on a miserable and uninviting night, and it is there that she heard tales of pirates and smugglers and wreckers that formed the basis for some of her characters. It sounded like an excellent place to visit. And so, with not-too-unwilling fiancée in tow, I proceeded on a dank Wednesday morning to the inn for a spot of reading and a drink of the rich atmosphere of deepest, darkest Bodmin.

The book of Jamaica Inn is by now a classic, an evocative work that conjures something of the spirit of early nineteenth-century society, and suggests something of the lawlessness and brutality of the oft-romanticised Cornish penchant for smuggling – still referred to somewhat proudly in those parts as the ‘free trade’. Du Maurier uses the barren and windswept setting superbly to craft a sense of uncertainty, of nameless dread and fear. Mary’s fear of the unknown activities of her brutal uncle, and her concern over who she can trust, is mirrored by the treacherousness of the landscape, which can swallow people whole in its bogs or fogs, or leave them perish from exposure on a bare tor as familiar paths disappear from view.

Unfortunately, the landscape of Du Maurier’s novel is much changed, and the inn barely recognisable. Whereas Mary arrived in an empty courtyard with no sign of friendly greeting, the current inn welcomes carloads and coachloads of tourists to visit its small museum, its Du Maurier-themed bars, its gift shop selling all things Jamaica Inn and Poldark, and its farm shop. The inn is accessed by a small road just off the A30, a major dual carriageway that takes travellers across the moor in minutes rather than the full day that would have once been required. The tors remain, and the views still warrant lengthy attention, but any sense of isolation or loneliness is lost. The inn is pleasant for all that, and the traditional front bars do offer a flashing ghost of an image of what the nineteenth-century taproom might have looked like. The museum is small but interesting, and the cafeteria at the back of the inn at least allows the multitude of visitors to get a coffee or a cream tea in a timely fashion, even if it does lack somewhat in atmosphere.

I didn’t get much reading done at Jamaica Inn – only a few pages, and a bit of flicking back and forth to seek descriptions of the inn to read within its hallowed precincts – but I thoroughly enjoyed sitting with my book and a hearty cream tea, absorbing the atmosphere of Bodmin Moor. The rest of the book I finished on a calm Devon beach, far from the brooding menace of an inn on the windswept moor. As a tourist attraction I’d recommend Jamaica Inn for a cup of tea and a bite to eat, or as a base for exploring some of the landscape thereabouts. Dozmary Pool – which local legend claims is the lake from which Excalibur emerged – is only a couple of miles distant, and to the north there are some spectacular tors to be climbed. As a book, I’d recommend Jamaica Inn as a thrilling tale of mystery, misdeeds and moorland, with a touch of the macabre thrown in for good measure. I would certainly be happy to read more of Du Maurier’s works. And thus ended my quest for a D; not quite plain sailing, but not so great a disaster after all.

Advertisements Share this: