In just a few weeks, the freshman class of 2021 will arrive in Austin and become a part of the University of Texas. Before the fall semester begins and schedules get busy, here are five things every UT freshman ought to know.

1. Know Your Forty Acres

Above: The UT campus at 21st Street and Guadalupe in 1899.

The city of Austin was founded in 1839 as the capital of the Republic of Texas. Surveyors laid out a series of city blocks between Waller and Shoal Creeks, set aside land at the top of a hill for a “Capitol Square,” named east-west streets for Texas trees, and north-south roads for Texas rivers.

The city of Austin was founded in 1839 as the capital of the Republic of Texas. Surveyors laid out a series of city blocks between Waller and Shoal Creeks, set aside land at the top of a hill for a “Capitol Square,” named east-west streets for Texas trees, and north-south roads for Texas rivers.

A year later, in 1840, additional land was surveyed to the north, and a square, forty-acre plot was informally labeled “College Hill,” (photo at left) bounded today by 21st and 24th Streets, Speedway to the east, and Guadalupe on the west. At the time, there were no firm plans to establish a university, and the people of Austin made no claims to the land. They built their homes and businesses around College Hill, and used the area as a favorite spot for weekend picnics. There is, in fact, no legal deed to the plot.

The Texas Legislature created the University in 1881 and Austin, by way of a controversial state-wide vote, won the main campus. Having waited decades, College Hill was at last put to use when UT was formally opened on September 15, 1883. Though the University grounds have expanded ten-fold, the campus is still known as the Forty Acres.

The Texas Legislature created the University in 1881 and Austin, by way of a controversial state-wide vote, won the main campus. Having waited decades, College Hill was at last put to use when UT was formally opened on September 15, 1883. Though the University grounds have expanded ten-fold, the campus is still known as the Forty Acres.

Above right: The Victorian-Gothic old Main Building, UT’s first campus structure, where the Tower stands today. (Explore the early UT campus here.)

2. Know Your Colors

It was a gloomy Tuesday morning, April 21, 1885, when UT’s first baseball team, along with most of the student body, arrived at the downtown Austin train station at Third Street and Congress Avenue. The group had chartered passenger cars bound for Georgetown, thirty miles north, where UT was to play its first-ever intercollegiate baseball game against Southwestern University. Just as the train was ready to depart, Miss Gussie Brown from (of all places) Orange, Texas, urgently announced the need for some ribbon to identify everyone as from the University of Texas.

It was a gloomy Tuesday morning, April 21, 1885, when UT’s first baseball team, along with most of the student body, arrived at the downtown Austin train station at Third Street and Congress Avenue. The group had chartered passenger cars bound for Georgetown, thirty miles north, where UT was to play its first-ever intercollegiate baseball game against Southwestern University. Just as the train was ready to depart, Miss Gussie Brown from (of all places) Orange, Texas, urgently announced the need for some ribbon to identify everyone as from the University of Texas.

Today, college fans show support for their teams by donning t-shirts, jackets, and caps. But in the 1880s, colored ribbons were worn on lapels. An enterprising male student often sported longer ribbons so he’d have extra to share with a pretty girl who had none.

Gussie’s two friends – Venable Proctor and Clarence Miller – always eager to impress the ladies, jumped off the train and sprinted north along Congress Avenue to the nearest general store. They asked the shopkeeper for three bolts of two colors of ribbon. “Which colors?” the merchant inquired. “Anything,” the students replied. After all, the train was leaving the station, and there was no time to be particular.

The shopkeeper gave them the colors he had the most in stock: white ribbon, which was popular for weddings and parties and was always in demand, and bright orange ribbon, because few bought the color, and the store had plenty to spare.

The shopkeeper gave them the colors he had the most in stock: white ribbon, which was popular for weddings and parties and was always in demand, and bright orange ribbon, because few bought the color, and the store had plenty to spare.

Right: The Austin railroad station at Third Street and Congress Avenue.

Loaded with supplies, Proctor and Miller ran back and boarded the moving train as it left for Georgetown. Along the way, the ribbon was divided and distributed to everyone except for a law student named Yancey Lewis, “who had evolved a barbaric scheme of individual adornment by utilizing the remnants.”

Unfortunately, it rained in the afternoon, the pitcher’s curve ball curved not, and Texas outfielders ran weary miles in a lost cause as they fell to an experienced Southwestern squad 21–6. The colors, though, had made their debut. There would be challengers, including gold and white, royal blue, and (most popular) orange and maroon, but a 1900 vote by students, faculty, and alumni settled the matter for orange and white.

Read the full story here: Orange and White

3. Know Your Mascot

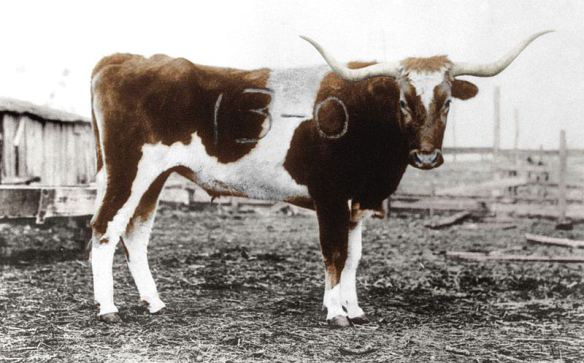

University of Texas athletic teams have been known as the “Longhorns” since 1904, but in the mid-1910s, a growing number of UT alumni wanted to see if a live longhorn mascot might be able to attend football games. In the fall of 1916, Texas law grad Stephen Pinckney, working for the U.S. Attorney General’s office, discovered what he thought would be the perfect candidate in West Texas. With $1.00 donations from 125 alumni, Pinckney arranged to purchase the steer and have it transported to Austin in time for the Thanksgiving Day football game between the University and Texas A&M.

University of Texas athletic teams have been known as the “Longhorns” since 1904, but in the mid-1910s, a growing number of UT alumni wanted to see if a live longhorn mascot might be able to attend football games. In the fall of 1916, Texas law grad Stephen Pinckney, working for the U.S. Attorney General’s office, discovered what he thought would be the perfect candidate in West Texas. With $1.00 donations from 125 alumni, Pinckney arranged to purchase the steer and have it transported to Austin in time for the Thanksgiving Day football game between the University and Texas A&M.

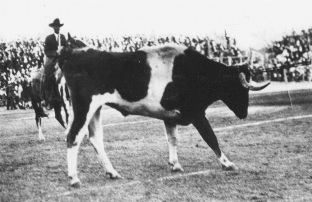

The longhorn made its debut at halftime and was presented to the students (photo above left), then taken to a South Austin stockyard for safe keeping and a formal portrait. He was named “Bevo,” thought to be derived from the word “beeve,” the plural for beef, and a slang term for a cow or steer. (Think of the name as “Beef-o.”)

The University community, though, wasn’t entirely sure what to do with their new addition. The gift had been made, but without any formal plans for feeding, caring, or transporting the steer. Besides, UT students already claimed to have a live mascot in Pig Bellmont, (right) a dog owned by Athletic Director Theo Bellmont. Pig lived on the Forty Acres, had a daily routine of greeting students in classrooms and in the library, and went to home and away football, baseball, and basketball games.

The University community, though, wasn’t entirely sure what to do with their new addition. The gift had been made, but without any formal plans for feeding, caring, or transporting the steer. Besides, UT students already claimed to have a live mascot in Pig Bellmont, (right) a dog owned by Athletic Director Theo Bellmont. Pig lived on the Forty Acres, had a daily routine of greeting students in classrooms and in the library, and went to home and away football, baseball, and basketball games.

Texas had won the football game 21-7, and some students pushed to have the steer branded with the score. Others thought it was cruel. As the campus community debated, a group of Aggie pranksters visited Austin in the wee hours of Sunday, February 12, 1917, broke in to the South Austin stockyard and branded the steer “13-0,” the score of the 1915 football bout A&M had won in College Station the year before.

Above: Bevo was branded “13-0” in February 1917.

A few days later, amid rumors that the Aggies planned to kidnap the animal outright, Bevo was safely transported to the Tom Iglehart ranch west of Austin. Six weeks later, the United States entered World War I, and the University transformed itself to support the war effort. Out of sight and off campus, the branded steer was all but forgotten until the end of the war in November 1918.

Since Bevo’s food and care cost the University sixty cents a day, and as the steer wasn’t believed to be tame enough to remain in the football stadium, it was fattened up and became the barbecued main course for the January 1920 football banquet. A delegation from A&M was invited to attend, “and the branding iron was buried and the resumption of athletic relations, after an unhappy period… duly celebrated.”

For the full story and more photos, see Bevo.

4. Know Your Hand Sign

Above: Harley Clark (right) and the 1955 UT cheerleaders.

Above: Harley Clark (right) and the 1955 UT cheerleaders.

Harley Clark was a head cheerleader in search of an idea. It was the second week of November, 1955, and the Texas Longhorn football team was getting ready to host sixth-ranked TCU in an important contest at Memorial Stadium. A torchlight parade across the Forty Acres and football rally in Gregory Gym had been scheduled for Friday night, November 11th, but Harley was looking for something to make it extra special and rouse a little more of the University of Texas spirit.

A few days before the rally, Harley was in the Texas Union (photo at right) when he saw fellow classmate Henry “HK” Pitts, who suggested that a hand sign with the index and little fingers extended looked a bit like a longhorn, and might be fun to do at rallies and football games. The Texas Aggies had their “Gig ‘em” thumbs-up sign, inspired while playing the TCU Horned Frogs. (“Gigging” is a term used to hunt small game – including frogs – with a muti-pronged spear.) With the TCU game coming up on Saturday, why can’t Texas fans have their own hand signal?

A few days before the rally, Harley was in the Texas Union (photo at right) when he saw fellow classmate Henry “HK” Pitts, who suggested that a hand sign with the index and little fingers extended looked a bit like a longhorn, and might be fun to do at rallies and football games. The Texas Aggies had their “Gig ‘em” thumbs-up sign, inspired while playing the TCU Horned Frogs. (“Gigging” is a term used to hunt small game – including frogs – with a muti-pronged spear.) With the TCU game coming up on Saturday, why can’t Texas fans have their own hand signal?

Harley liked the idea, and decided to introduce it at the Gregory Gym rally. He demonstrated the sign to the crowd and promptly declared, “This is the official hand sign of the University of Texas, to be used whenever and wherever Longhorns gather.” The students and cheerleaders tried it out, and Harley led a simple yell, “Hook ‘em Horns!” with hands raised. (In this case, a tradition has two founders. HK Pitts was in charge of “research and development,” and Harley Clark took on “marketing and sales.”)

Above: A tradition is born. The moment in Gregory Gym when the “Hook ’em Horns” hand sign was first introduced to UT students. Click on an image for a larger view.

Immediately after the rally, Harley was confronted by a furious Arno Nowotny, the Dean of Students. “How could you say the hand sign was official?” the dean wanted to know. “Has this been approved by the University administration?” Harley admitted that the idea hadn’t been approved first, but the cat was already out of the bag – or the longhorn was already loose in the pasture. At the football game, the student section practiced what they’d learned the night before, and the alumni were quick to follow. By the end of the game, the stadium was full of “Hook ‘em Horns” hand signs.

The full story is here: Hook ’em Horns

5. Know Your Tower

The Main Building, with its 307-foot Tower, is the definitive landmark of the University. For eighty years, it’s quietly watched over the campus bustle, breaking its silence every quarter hour to remind everyone of the passing of the day. Bathed in warm orange lights to announce honors and victories, crowned in fireworks at the climax of spring commencement ceremonies, it’s been a backdrop for freshman convocations, football rallies, concerts, and demonstrations. Architect Paul Cret intended it to be the “image carried in our memory when we think of the place,” though author and UT English instructor J. Frank Dobie, incensed that a state so rich in land would build something better suited to New York City, branded it a “toothpick in a pie.”

The Main Building, with its 307-foot Tower, is the definitive landmark of the University. For eighty years, it’s quietly watched over the campus bustle, breaking its silence every quarter hour to remind everyone of the passing of the day. Bathed in warm orange lights to announce honors and victories, crowned in fireworks at the climax of spring commencement ceremonies, it’s been a backdrop for freshman convocations, football rallies, concerts, and demonstrations. Architect Paul Cret intended it to be the “image carried in our memory when we think of the place,” though author and UT English instructor J. Frank Dobie, incensed that a state so rich in land would build something better suited to New York City, branded it a “toothpick in a pie.”

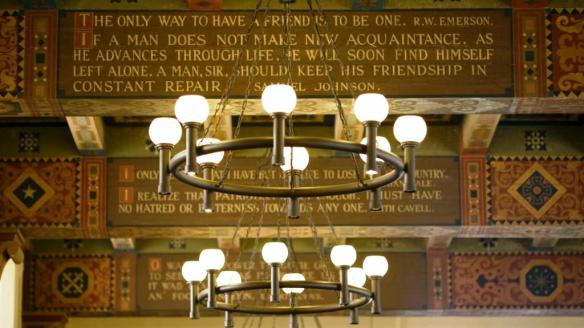

Opened in 1937, the Main Building was created to house the University’s central library. Along the east and west sides of the building, a pair of spacious reading rooms, labeled the “Hall of Texas” and the “Hall of Noble Words,” were connected to a great central reference room. Made with liberal use of oak and marble, the room was decorated with the six seals of Texas. (A life sciences library is still housed in the Main Building, and a visit to see these great halls is highly recommended. The Hall of Noble Words is a popular study place for students.)

Above: The ceiling of the Hall of Noble Words.

Rising twenty-seven floors above the reading rooms, the Tower contained the library’s book stacks. Made of Indiana limestone, it was financed through a grant from the Progress Works Administration, a New Deal program created during the Great Depression. As a closed-stack library, its patrons searched an immense card catalog to identify their selections, and then requested books at the front desk. Orders were forwarded upstairs to one of the Tower librarians, who sometimes wore roller skates to better navigate the rows of bookshelves. Once found, books were sent downstairs in a special elevator to be checked out.

Rising twenty-seven floors above the reading rooms, the Tower contained the library’s book stacks. Made of Indiana limestone, it was financed through a grant from the Progress Works Administration, a New Deal program created during the Great Depression. As a closed-stack library, its patrons searched an immense card catalog to identify their selections, and then requested books at the front desk. Orders were forwarded upstairs to one of the Tower librarians, who sometimes wore roller skates to better navigate the rows of bookshelves. Once found, books were sent downstairs in a special elevator to be checked out.

As both enrollment and the library’s holdings grew, the waiting time for a book extended to more than half an hour. The need for an open-stack library led to the construction of the Undergraduate Library and Academic Center in 1963 (now the Flawn Academic Center), and the Perry-Castaneda Library in 1977.

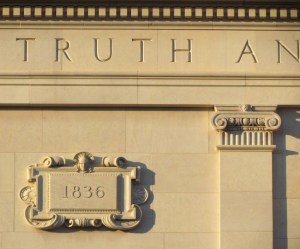

Symbolically, architect Paul Cret intended the Tower to be the University’s iconic building, and sought to give it an “appropriate architectural treatment for a depository of human knowledge.” The ornamentation on the building was meant to convey its purpose as a library as well as to the mission and aspirations of the University. Names of literary giants – Plato, Shakespeare, and Mark Twain, among them – were carved in limestone under the tall windows along the east and west sides. Displayed in gold leaf on the north side of the Tower were letters (or cartouches) from five dialects that contributed to the development of English language: Egyptian, Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. The biblical quote inscribed above the south entrance, “Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free,” was selected by the Faculty Building Committee as suitable for those who came to use the library. “The injunction to seek truth as a means to freedom is as splendid a call to youth as we can make,” explained committee chair William Battle. (See: The Inscription.)

Symbolically, architect Paul Cret intended the Tower to be the University’s iconic building, and sought to give it an “appropriate architectural treatment for a depository of human knowledge.” The ornamentation on the building was meant to convey its purpose as a library as well as to the mission and aspirations of the University. Names of literary giants – Plato, Shakespeare, and Mark Twain, among them – were carved in limestone under the tall windows along the east and west sides. Displayed in gold leaf on the north side of the Tower were letters (or cartouches) from five dialects that contributed to the development of English language: Egyptian, Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. The biblical quote inscribed above the south entrance, “Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free,” was selected by the Faculty Building Committee as suitable for those who came to use the library. “The injunction to seek truth as a means to freedom is as splendid a call to youth as we can make,” explained committee chair William Battle. (See: The Inscription.)

Placed alongside the literary images were familiar Classical symbols. The lamp of learning, the face of Athena as the goddess of wisdom, and rows of scallop shells – associated with Venus as the goddess of truth and beauty – were all added to the south façade, carved in place by Italian stone masons. Learning, wisdom, truth, and beauty: values long associated with the purpose of higher education.

Placed alongside the literary images were familiar Classical symbols. The lamp of learning, the face of Athena as the goddess of wisdom, and rows of scallop shells – associated with Venus as the goddess of truth and beauty – were all added to the south façade, carved in place by Italian stone masons. Learning, wisdom, truth, and beauty: values long associated with the purpose of higher education.

The most colorful decorations were hung along the east and west sides of the building, just below the broad eaves, where artful representations of a dozen university seals (above right) were meant to convey a history of higher education, as well as proclaim UT’s own aspirations to be a “University of the first class.”

At night, the Tower takes on a different symbolic meaning when it glows orange to announce an athletic victory or an academic achievement. In the case of a national championship, a number “1” is displayed in the windows – a favorite sight for every Longhorn fan.

Above: An orange Tower with a “1” on all four sides for a national championship.

For more reading and photos: How to Build a Tower, The Main Building Seals, and UT Tower Lighting Configurations

Also see: Advice for UT Freshmen