Flood of Fire is the third and final novel of Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis Trilogy and once I began reading it, I felt I was onto Ghosh’s game. Though it is called the ‘Ibis Trilogy’, the ship, which was absent for most of the second novel, River of Smoke, is not the central focus of the story. And, though Ghosh has evocatively recreated the amazing locations of the novel – Calcutta, Bombay, Mauritius, Singapore, Guangzhou, etc, of the 19th century – and the incredible events leading up to the First Opium War; it is the characters who are the true stars of the trilogy.

These disparate characters, whose main connection to each other was their shared, life-changing, experience aboard a short voyage on the Ibis, are the reason these books are so engrossing and they will remain with the reader despite everything Ghosh provides besides. The best thing about Flood of Fire, therefore, is the return and continuation of the stories of characters we already love and the addition of several new ones.

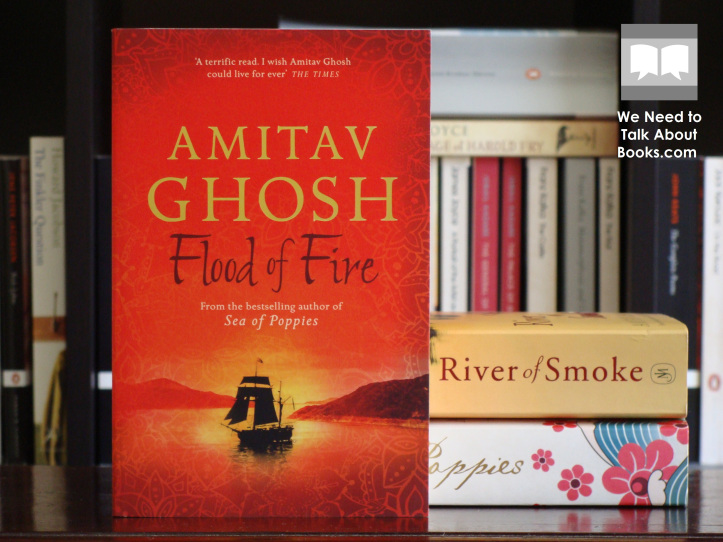

(Note: because this novel is the third in a trilogy, this review contains a couple of spoilers with regards to the first and second novels; Sea of Poppies and River of Smoke respectively)

Neel, the deposed Raja and escaped convict was probably my favourite character in the first two novels, though he has some competition for that position in Flood of Fire. When we begin, Neel is still living in Guangzhou but is now in need of new employment while still haunted by the loss of his family. The growing possibility of war with Britain means that a man with Neel’s knowledge is valuable to those in China who make their trade in diplomacy and intelligence gathering. For the first time we hear Neel’s own thoughts in the first-person via his journal which is one of the aspects of Flood of Fire that I loved most.

Shireen Modi is one of the new characters we are introduced to. She is the wife of Bharam Modi; opium trader and, it is fair to say, the main character of the previous novel, River of Smoke. A deeply religious and traditional Parsi woman with a strong moral sense, Shireen has lived largely content in her role of dutiful wife and mother. When the news reaches her in Bombay that her husband has died, that he lost everything on his final voyage and left behind huge debts, Shireen is filled with shock and anxiety. It is possible that Britain will go to war with China over the matter of the opium trade and that reparations for Bahram’s losses might be made, but there is no one to make her late husband’s case.

In a move that scandalises her family, Shireen decides she will go to China herself. With her children grown and married and her husband dead, she has little to hold her back and she has an ally in her late husband’s friend; Zadig Karabedian. Like her husband in the previous novel, her journey will be a severe test as her sense of duty and moral right clashes with the restrictions that religious observance and tradition otherwise place on her.

Kesri Singh, a Havildar in the Bengal Native Infantry’s 25th Regiment, is another new character in Flood of Fire. He is also the older brother of Deeti, one of the main characters in the first novel of the trilogy, Sea of Poppies. Kesri is struggling to make sense of the events concerning Deeti from Sea of Poppies; a subversion of her duties to her husband and religion, running away with another man, a man who would go on to murder his regiment’s former Subedar, the older brother of Kesri’s current superior officer.

Kesri has formed a close relationship with his British officer, Captain Mee. A soldier of high integrity and professionalism, Mee is also a quick-tempered drinker and gambler. Seeking more action and greater rewards, Mee has volunteered for an overseas expedition and wants Kesri to come with him. Kesri though, has reached a point of exhaustion in his military career and is uncertain. He is becoming increasingly disillusioned; questioning his own motives for his past behaviour and wondering whether his ambitions for himself were ever likely to be fulfilled.

When he had pulled out his dripping sword, Kesri saw that the man’s eyes were still open. For a few seconds of life that remained to him, the man fixed his gaze on Kesri. His expression was one that Kesri had seen before, on campaigns in the Arakan and the hills of eastern India – he knew it to be the look that appears on men’s faces when they fight for their land, their homes, their families, their customs, everything they hold dear.

Seeing that expression again now it struck Kesri that in a lifetime of soldiering he had never known what it is to fight in that way – the way his father had fought at Assaye – for something that was your own; something that tied you to your fathers and mothers and those who had gone before them, back into the dimness of time.

An unnameable grief came upon him then; falling to his knees he reached out to close the dead man’s eyes.

It is said the coming conflict in China will usher in a new era in warfare; where war will be fought by corporations rather than governments and the rewards could be very lucrative. Going with Mee to fight in China may allow Kesri to end his career with something to show for it.

You see, said Compton bitterly. This is what happens when merchants and traders begin to run wars – hundreds of lives depend on bribes.

Zachery Reid was the most conspicuous absence in River of Smoke. The African-American ship’s carpenter, who rose quickly to be the Second Mate aboard the Ibis, faced charges for the events that took place aboard that fateful voyage. Thanks to testimony from other officers aboard and from his employer Mr Burnham, Zachery has been cleared but is left with substantial legal fees. To help him, Mr Burnham offers Zachery the job of refitting a budgerow, a pleasure boat formerly owned by Neel when he was Raja, which Burnham has taken possession of.

In doing so, Zachery comes under the watchful eye of Mrs Burnham. At first appearance, Mrs Burnham seems every bit the complement of her husband. She is a woman that commands a high degree of respect from her social position, her wealth, and for her faith and moral standing. Mrs Burnham finds such standards to be lacking in Zachery and so she takes it upon herself to school him in the latest theories in Christian ethics. What Zachery comes to realise in his private moments with Mrs Burnham is that she is a deeply unhappy still-young woman, trapped in a marriage with little affection and by the requirements of a woman in her position.

Zachery was one of my favourite characters in the first novel of the series where his transformation from ship’s carpenter to officer began under the guidance of the lascar Serang Ali. Now, with the help of both Mr and Mrs Burnham, Zachery’s transformation continues. Tempted by the possibility of becoming a wealthy opium-trading sahib himself, Zachery’s ambition catches fire. His chief motivations, though, are greed and hurt and he spares little thought to how his character is being affected and what he is turning into.

‘I have become what you wanted, Mrs Burnham,’ he said. ‘You wanted me to be a man of the times, did you not? And that is what I am now; I am a man who wants more and more and more; a man who does not know the meaning of “enough”. Anyone who tries to thwart my desires is the enemy of my liberty and must expect to be treated as such.’

Other characters readers of the first two novels will be familiar with also make a return in Flood of Fire – Paulette Lambert, Baboo Nob Kissin, Jodu, Robin Chinnery, Serang Ali and others. All connected by the bond of the Ibis.

I do not want to say much about the plot of Flood of Fire. Suffice to say that the previous novel left us on the cusp of the First Opium War and the story of Flood of Fire is how these various characters are all drawn into its vortex in southern China with unexpected outcomes for all.

How was it possible that a small number of men, in the span of a few hours or minutes, could decide the fate of millions of people yet unborn? How was it possible that the outcome of those brief moments could determine who would rule whom, who would be rich or poor, master or servant, for generations to come?

Nothing could be a greater injustice, yet such had been the reality ever since human beings first walked the earth.

Where the appeal of Sea of Poppies was its introduction to an amazing world and characters and a palpable sense of adventure; the appeal of River of Smoke was the story of Bharam Modi and the growing tension in Guangzhou; the appeal of Flood of Fire is the culmination of all that has been building. And it is a fantastic ending. There is greater action and hence tragedy, greater connection and hence love and heartbreak, more answers and hence closure.

As well as the strengths of the characters and the plot, Flood of Fire has all the thematic appeal of the earlier novels. But like the plot, I do not want to say much more about them. I’ve already mentioned some of the key ones in my earlier reviews, such as – the impact of colonisation on rural India and its role in creating poverty; opium’s role in funding the British Empire; British expansion in Asia motivated by power and greed and endorsed by notions of free trade, Christianity and racial superiority.

On shoulders such as these will fall the task of freeing a quarter of mankind from tyranny; of bestowing on the people of China the gift of liberty that the British Empire has already conferred on all those parts of the globe that it has conquered and subjugated. […]

It is you, gentlemen, who will give to the Chinese the gifts that Britain has granted to the countless millions who glory in the rule of our gracious monarch, secure in the knowledge that there is no greater freedom, no greater cause for pride, than to be subjects of the British Empire. This is the divine mission that the Almighty Himself has entrusted to our race and our nation. […]

This was a predestined conflict, as inevitable as the struggle as the struggle between Cain and Abel. On one side stands a race that is mired in depravity, tyranny, self-conceit and evil; ranged on the other side are the truest, most virile representatives of freedom, civilisation and progress that history has ever known.

But Flood of Fire gives the reader a few new themes to consider. One is the role of Indian soldiers, sepoys, serving in the British and the East India Company’s armies. The reader is enlightened as to their origins, motivations, experiences and importance by the backstory of Kesri’s life, his experiences on the Chinese expedition and by Neel trying to explain to his Chinese friends why Indians would fight for the Empire that is otherwise oppressing them, even when they are second-class citizens within the army as well.

Despite all their cacklings about Free Trade, the truth was that their commercial advantages had nothing to do with markets or trade or more advanced business practices – it lay in the brute firepower of the British Empire’s guns and gunboats.

The knowledge is traded both ways so, through Neel, we learn of China’s own imperialist ambitions – an expansion into Tibet, conflict with Gurkhas in Nepal – and the relative cultures and philosophies of China and India that make them vulnerable to European colonisation.

Compton says that for centuries people in Guangdong have taken comfort in the thought that saang gou wohng dai yuhn – ‘the mountains are high and the Emperor is far away’. What is the sense of stirring the pot that is sure to scorch you if it spills over?

I suppose this is much how things were in Bengal and Hindustan at the time of the European conquests, and even before. The great scholars and functionaries took little interest in the world beyond until suddenly one day it rose up and devoured them.

Another theme, that has been true of the whole trilogy but really becomes more noticeable in Flood of Fire, is of women confined by religion, tradition, custom and the men in their lives who enforce them. The women of these novels risk their lives in pursuit of their independence; each in their own way, sometimes by determination, sometimes by fortune and not always with success. This was true of the stories of Deeti and Paulette Lambert in the earlier novels, and of Shireen Modi and Mrs Burnham in Flood of Fire.

I loved this trilogy and I did not find much at all to dislike. Because Flood of Fire is the final novel in the trilogy, various plot lines, and the characters riding them, come together. Inevitably, this leads to the potential for love, sex and romance between them. I am not convinced that Ghosh handled this aspect well. To be fair, I think it is something a lot of writers struggle with and it is so subjective that even when they do it relatively well, it is difficult to please all readers. There were a few moments I found a little sappy, but other readers may not have minded at all. I am willing to forgive Ghosh for any such minor moments.

Also forgivable are the moments when the plot lines are brought together by the revelation of Dickensian coincidences. Though I sometimes questioned the plausibility of these moments, I quickly forgave them because, as when reading Dickens, they serve to build more potential to the story like throwing more fuel on a fire.

I also don’t want to say too much about the strengths of Ghosh’s style since I have covered them in the earlier reviews. As in the previous novels, there were times when I wondered about some of the diversions the stories took. I could not see the point of them. Then Ghosh delivers a fantastic blow that I did not see coming and makes it all meaningful again.

Again, his ability to recreate these exotic locations of the past is remarkable and a real treat. So too his ability to construct some amazing evocative scenes in the story. His extensive research is also on display. Flood of Fire ends with an epilogue where Ghosh shares five-and-a-half pages of source materials he used. Ghosh hints at the factual origins behind the novels; of Neel’s archive which was smuggled out of China before WWII and teases that there is potentially more story to tell.

I don’t usually recommend books. When I think of my own favourite books, there is no obvious pattern that may lead me to think of what else I may enjoy and I believe the same is true for many people. There is also that aspect of human nature that makes us resist things that are recommended to us. Nevertheless, after reading the Ibis Trilogy, I feel compelled to give it a very strong recommendation.

That’s because it has such broad appeal. If you like contemporary literature; the sort of books that tend to get nominated for literature prizes, then you will enjoy the skill of Ghosh’s writing. If you like historical fiction, especially when it has been extensively researched and in the hands of a writer who can bring the worlds of the past alive; you will love the Ibis Trilogy. If you are looking for diversity or the ‘exotic’ in your reading, the Ibis Trilogy has a variety of male and female characters of differing ethnicities, classes, sexualities and outlooks, thrown together in lands far from their homes. And if you are simply after an entertaining read, that would the Ibis Trilogy’s strongest point. It is a powerful story of love and heartbreak, betrayal and revenge, art and science, trade and war, life and death. I cannot recommend it strongly enough to anyone who is searching for quality reading.

Finally, if you like to read fiction that is relevant, the Ibis Trilogy – with its themes of global trade and war, opium, the corruption of religion and capitalism by those seeking wealth and power, and the awakening giants of India and China – could hardly be more relevant.

It is the destiny of the English to bring about the world’s end; they are but instruments of the will of the gods. […] That is why the English have come to China and to Hindustan: these two lands are so populous that if their greed is aroused they can consume the whole world. Today that great devouring has begun. It will end only when all of humanity, joined together in a great frenzy of greed, has eaten up the earth, the air, the sky. […] You and I are fortunate in having been chosen to serve this destiny: the beings of the future will be grateful to us. For only when this world ends will a better one be born.

For my reviews of the other novels of the Ibis Trilogy, see here.

Advertisements Share this: