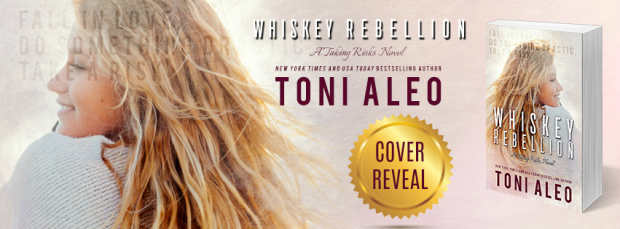

When I read Rachel Cusk’s Giller shortlisted novel Outline two years ago, I had a luke-warm response to it. In fact, I returned it to the library after reading only half the book. So when Transit made it onto the list this year, I felt a little… apprehensive.

When I read Rachel Cusk’s Giller shortlisted novel Outline two years ago, I had a luke-warm response to it. In fact, I returned it to the library after reading only half the book. So when Transit made it onto the list this year, I felt a little… apprehensive.

Well there is something to be said for low expectations, because I liked it. “Love” might be too strong a word, but “like” will do.

So I asked myself : what’s different? (And I know I’m not the only one who didn’t get along with Outline.) I think my issue with Outline was that I couldn’t connect with the characters. I didn’t care about anyone in the book, so there was no reason to keep reading.

The structure and style of writing in Transit is the same, but in Transit Faye is closer to home. The people she runs into and speaks to and shares stories about are closer to her own life. For this reason I think there is more opportunity to get to know her. According to Cusk, in an interview with Trevor Corkum at 49th Shelf, ““Outline describes a state of increasing detachment from the contract for living, yet the narrator does live.” In Transit she “wanted to examine the terms of that survival and what kind of future it suggested.”

Some of the people she runs into, or meets up with in this book that contribute to a more complete picture of Faye are: an ex-boyfriend who is since married with a daughter, the men doing renovations on her apartment, a couple of writers she meets at a literary event, one of Faye’s writing students, her friend Amanda who works in fashion, a man she goes on a date with, and her cousin Lawrence and the guests at his house party.

I liked Faye’s basement neighbours, who seemed totally unnecessarily nasty to Faye. But at least they were entertaining.

An opportunity missed, I think, is getting to see Faye through the eyes of her children. They are staying with their dad during Transit, due to renovations at their new apartment, so there are brief mentions of her sons and a couple of phone calls but that’s it. Maybe she’s saving it for book #3…

I thought the best part of the book was the last chapter when Faye is visiting Lawrence’s house and the children are present; it adds some interest to the story to read about the adults and children interacting with each other. In the interview at 49th Shelf, Cusk says that she is surprised “that there hasn’t been more awareness of its central theme, which is children and the false morality that is displayed in so many of our dealings with them. I think I would point to the last chapter of the novel as the expression of my own views about the true nature of responsibility.” I wouldn’t have picked up on that myself.

Rachel Cusk is good at getting details right; the kind that make you think “Yes!”. For example, have you ever spoken back to the voice that is mysteriously or magically able to give you directions when you’re driving?

A friend of mine, depressed in the wake of of his divorce, had recently admitted that he often felt moved to tears by the concern for his health and well-being expressed in the phraseology of adverts and food packaging, and by the automated voices on trains and buses, apparently anxious that he might miss his stop; he actually felt something akin to love, he said, for the female voice that guided him while he was driving his car, so much more devotedly than his wife ever had.

And her idea about marriage…

I said it seemed to me that most marriages worked in the same way that stories are said to do, through the suspension of disbelief. It wasn’t, in other words, perfection that sustained them so much as the avoidance of certain realities.

In the end, for me, Faye’s character still isn’t quite enough to pull me into the book entirely. She still feels too remote, like she’s being held at arm’s length. Which is probably intentional and says something about Faye as a person, but for me it doesn’t work. I am now, however, curious about how I’ll feel about the third book in this series and will probably read it when it comes out.

For a long time, I said, I believed that it was only through absolute passivity that you could learn to see what was really there. But my decision to create a disturbance by renovating my house had awoken a different reality, as though I had disturbed a beast sleeping in its lair. I had started to become, in effect, angry. I had started to desire power, because what I now realized is that other people had had it all along, that what I called fate was merely the reverberation of their will, a tale scripted not by some universal storyteller but by people who would elude justice for as long as their actions were met with resignation rather than outrage.

How do you feel about Outline and Transit? Have you read any of her other books? Do you think it has a good chance of winning the Giller this year?

Further Reading:

Review at Buried in Print: “Some readers will inevitably feel as though they are standing on the sidewalk, observing the lights from the darkness. All the glitter disorienting, maybe even unpleasant. Other readers will pull open the door and take a seat. Marvel at the kaleidoscopability of it all.”

Review at The Book Binder’s Daughter: “There is always the feeling in a Cusk novel that a simple description… has a much heavier and deeper meaning than what we encounter at first glance.”

Review in The New York Times: ““Transit” is a calm novel about chaos. Faye is having her tatty new apartment renovated, and the noise and squalor reflect the dishevelment in each corner of her life.” and “…Ms. Cusk’s novel bears down on topics like power and powerlessness, freedom and fate, love and its opposite. The most important thing we have in this world, “Transit” suggests, is other people, and it’s very hard to find the good ones…”

Advertisements Share this: