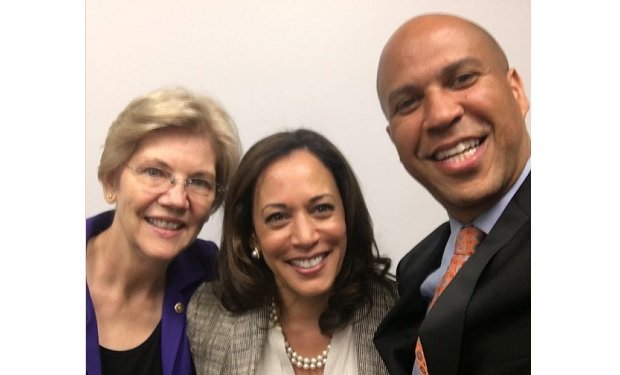

Rosemary Allen, Kevin Hurley. All photos: New York City Players

Rosemary Allen, Kevin Hurley. All photos: New York City Players

Good Samaritans: Performance Art Versus Theater, Or Are They One and the Same?

By Ross

What should one expect when walking into a Richard Maxwell play? Depends on who you ask? Performance art? or live theatre? I have never had the opportunity nor have I heard much about Maxwell, but he is a well-known fixture worldwide for his experimental theatrical writing and directing style. When I took my seat at the Abrons Art Center on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, I knew nothing except that this play, Good Samaritans, is critically acclaimed and has toured the world. Returning to New York, it is being presented by the New York City Players with the original cast from its Obie-winning St. Ann’s Warehouse production back in 2004. So I was intrigued.

At first Maxwell’s style is off putting. The set is stark and the lighting fluorescent. Extreme realism is presented here in full glorious action (set, lights, costume design: Stephanie Nelson). It felt like we were be invited in to watch these characters speak words and phrases that many would describe as more of our ‘inner chatter’, rather than external dialogue. It had an ego/id quality to the dialogue that was complicated to take in at times. The speech was also being presented with a very flat delivery, in a way that both felt devoid of love and attachment, while holding on to a sliver of care and humanity. I can’t say that I stayed intrigued very much once it got started.

After the production, reading the press release and some different articles from Bomb (John Kelsey, Fall 2008) and ArtForum (Maxwell, David Velasco, April 25, 2012), one particular quote struck me as relevant, “the particular awkward liveness of Richard Maxwell’s production has something to do with stripping theatre down to a particular truth”. The idea, of ‘stripping away’ all the dramatics and emotive acting intentions to delve into the true inner meaning of people connecting as best as they know how, yet also presenting the concept of our disconnection, seems interesting but uncomfortable. He seems to be exploring the disconnect of words spoken and the inner meaning of what is not being said. Which after reading the interview, made some sense, artistically speaking.

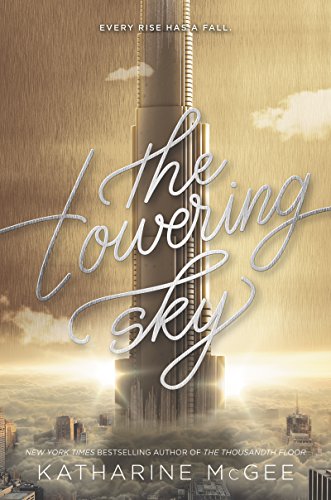

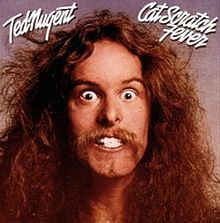

Rosemary Allen, a former nurse and actress who’s been connected to this piece since performing in it in Australia, Europe and at St. Ann’s from 2004-2006, feels perfect for this style and the role of caregiver and rehab coordinator. Straightforward and plain spoken, she has reduced the theatricality in her delivery but oddly enough, the emotion still registers; sometimes with subtle intensity. She runs a shelter or rehab housing center and deals with recovering addicts day in and day out. She has the worn out physicality of a social worker that has devoted herself to helping people all her life, without receiving much in return. As a psychotherapist myself, something in her manner resonated in me initially, although the actual words spoken were jarring.

After singing a song (numerous original songs written by Maxwell) as she gazes out the high basement window, we register her realness, not embellished by the artifice of theater, as her singing is off key and plain. The singing throughout this play is at best engaging; sometimes sweet or melancholy, but rarely beautiful in tone (fantastic performances by the musicians James Moore/guitar and David Zuckerman/piano). In walks a man, (Kevin Hurley); an addict, a drunk, or a homeless man? We never are sure, but these two spar, and argue, while Rosemary tries to engage and settle him in to this rehab environment. Over the course of the 90-minute play, a bizarre and abrupt romantic affair blossoms, culminating with the closest thing to a harmonious love song being sung by the two. It’s hard to fathom this interaction but as the interview from Bomb explains, Maxwell likes to engage in “strangely simplified, sometimes explosive action”, and that is definitely on display here. Surprisingly, when Kevin abandons her, in what appears to be a heartless and selfish act, I found myself feeling Rosemary’s pain of abandonment even when the delivery of the spoken word and the believability of the relationship was so difficult to believe.

It’s a strange brew, this theatrical piece. I would tend to label this more as ‘performance art’ over theatre, as it seems to require reading the writer’s artist statement to fully understand the experience, and even then, it’s hard to completely engage with. It’s equal to a visit to a modern art gallery, much like the one I passed on Grand Street after the show. To appreciate the pieces of sculpture, one needs to read about the intentions of the artist. I can appreciate that personal involvement in the process, especially with modern art installations, but I’m not one of those people who feel theatre should require reading prior to the performance in order to understand and become invested. In order to dig deeper into the meaning and the art of a play, I do believe that an artist statement can enhance a performance on many intellectual levels. That is an idea I can wrap my head around, but in the moment of viewing, I found the piece difficult to engage with. This performance piece is not for this particular theatre addict, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have its place in the world of art and performance. Just not mine. Maxwell might disagree, and that, my friends, is the beauty of art and theatre.

Advertisements Share this: