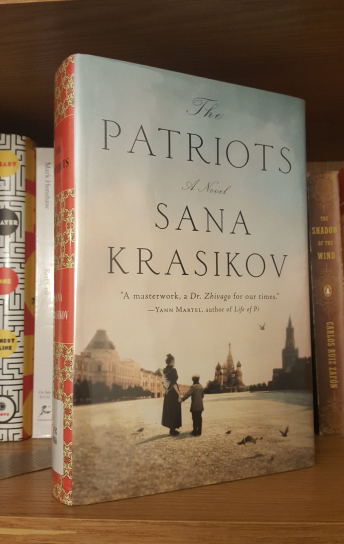

- What: The Patriots

- Who: Sana Krasikov

- Pages: 538

- Genre: Historical fiction

- Published: 2017

- The lit:

of 5 flames

of 5 flames

Textbooks can never do history or its victims much justice. That’s where novels supplement them, add context, and bring them to life. They teach us something new and evoke feelings that textbooks never can; that’s exactly what The Patriots did for me.

Sure, every American kid learned that the Cold War threatened the institution that was the “Beacon on the Hill” and all of its principles. But somehow my history classes glazed over the passion, the unity, the rumblings, and even the atrocities of the Soviet Union during this time. But just as important, it left out stories of those Americans who felt a connection to the U.S.S.R., took a chance, and left their homes for this place of the future. Sana Krasikov vividly showcases these narratives in her 2017 debut novel. With her evocative words and strong storytelling, The Patriots doesn’t allow these defining (and more importantly, those less so) moments to go unnoticed by making a four-flame impact.

The Patriots spans three generations and seven decades while highlighting the gradual yet sudden changes across Russia and starring foreigners who felt a draw to the new nation. Cutting back and forth between the lives of Florence Fein, her son, Julian, and her grandson, Lenny, from 1932 to 2008, the story touches on an uneasy mother/son relationship with the birth and death of the Soviet Union as the center stage.

Feeling helpless yet hopeful for a more meaningful life, in 1934, Florence leaves an unpromising and unfair Brooklyn for her ancestors’ homeland of Russia despite her parents misgivings. Even though a lover inspires the her journey, its her idealistic nature and pursuit of justice that keeps her in Moscow.

Throughout her life, Florence faces poverty and an increasingly corrupt bureaucracy, eventually being locked inside the country (both physically and emotionally) that once inspired her and forgotten by the country she tried to escape. In 1949, Florence is taken from her family and dragged to a labor camp in Siberia due to false allegations of dispensing anti-Soviet propaganda. While there, she experiences emotional and physical trauma, much of which she can’t discuss with anyone, let alone her unforgiving son, years later.

Fast forward 50 years, and Julian, who was taken from Florence during her enslavement, is trying to convince his son to return to the U.S. from Russia despite his yearning for “experience.” Like his grandmother, he values playing a role in history and has an unexplained loyalty to Russia.

“My life’s been an adventure, is what I’m saying. I know that doesn’t mean much to you, but I can honestly say I’ve experience things about myself–” — Lenny from The Patriots

Krasikov’s writing takes you directly to the Soviet Union, to the anti-bourgeois climate, to a place struggling with its own experiment, and to the ultimate downfall of such harsh totalitarianism. But the beauty in her work goes beyond bringing light to an injustice because it’s more complex than that; it’s provocative.

Proactive in that it doesn’t simply denounce Russian and communist theories. It also questions the legitimacy of American democratic and capitalist ideals while considering the positives of the former. Despite the eventual injustices of the U.S.S.R, was its foundation completely insincere? Is the U.S., as the “leader of the free world,” as idealistic and free of faults as it may think? These are the questions that Florence not only ponders herself but also makes her audience consider. To force a reader to question his or her preconceived notions is an art form at which Krasikov excels.

“She had wanted to skip past all those prohibitions and obstructions, all the prejudices and correctness, and leap straight into the future. That’s what the Soviet Union had meant to her back then–a place where the future was already being lived.” — The Patriots

Connecting Florence’s story to Lenny’s half a century later highlights the relevance and universality of her struggle as he deals with similar issues in his career. Even though the Soviet Union experiment has ended, corruption and injustice haven’t fully dissipated. The New York Times’ Nathaniel Rich praises these scenes in his review. “The petro-corruption scenes, together with those describing Florence’s impossible struggles against Soviet bureaucracy, are the novel’s best, belonging to a rich tradition of Russian writing about the petty absurdities of life under totalitarian rule — life, as Julian puts it, in the ‘logic-free zone.'” he writes. Fifty years later, and these issues still exist on some level.

Although these connections between past and present add another level of depth and complexity, they were sometimes hard to follow, which caused a lot of backtracking on my part. I don’t need chronology, but smoother transitions are helpful. Furthermore, some points in Florence’s life aren’t connected that well. In one chapter, she has bed bugs while living in a crowded dormitory in Magnitogorsk. The next time we hear from her, she’s working as a translator for the Soviet State Bank in Moscow without any indication of how she got there.

Not that these holes took away from the story though. In the end, I wasn’t thinking about the specifics of spring 1934. I was thinking of all the complex questions Krasikov raised, the persecution that Florence and others faced (things I had never learned before), and how these issues and experiences tie into today’s politics. Tackling all of that is quite the hefty feat, but if you leave your reader wondering about these things days after they’ve finished the book, then, as a storyteller, you’ve succeeded.

“Old age made you discover that it wasn’t the big mistakes but the small ones that laid claim to your regrets.” — The Patriots

Share this: