Do more options lead to better outcomes?

In a perfect world, you could evaluate all your options and choose the best one.

But in the real world, when you have a lot of options, it takes too much effort to evaluate all of them. In fact, with enough choices, the cost of evaluating all possible options exceeds the perceived benefit of the outcome of any choice—and we give up on choosing at all.

You may have found yourself experiencing this while shopping. You’re looking for a basic item at the grocery store and faced with dozens of options. You need to decide based on price, brand, flavor, or any number of other categories. Often, the job of choosing becomes overwhelming. You walk away.

You may have heard of the now-famous “jam study,” which shows more choice can lead to undesirable outcomes:

On one day, shoppers at an upscale food market saw a display table with 24 varieties of gourmet jam. Those who sampled the spreads received a coupon for $1 off any jam. On another day, shoppers saw a similar table, except that only six varieties of the jam were on display. The large display attracted more interest than the small one. But when the time came to purchase, people who saw the large display were one-tenth as likely to buy as people who saw the small display.

The study was conducted by Sheena Iyengar. In her excellent book, The Art of Choosing, you can find numerous examples of the same outcome from several companies:

“When Proctor & Gamble winnowed its 26 varieties of Head & Shoulders anti-dandruff shampoo down to 15, eliminating the least popular”, sales jumped by 10 percent.

And here’s another one:

“In a similar move, the Golden Cat Corporation got rid of its ten worst-selling small-bag cat litters, which led to a 12 percent bump in sales and also cut distribution costs in half. The end result was an 87 percent profit increase in the small-bag litter category.”

In other words, as Barry Schwarz writes in The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less:

What’s the optimal number of choices?“As the number of choices grows further, the negatives escalate until we become overloaded. At this point, choice no longer liberates, but debilitates. It might even be said to tyrannize.”

Too many options is a bad thing.

But having no options is worse than having too many options. Even though making choices can be difficult, we’d still rather have the option to make a choice. We want the freedom to choose, or at least we want the perception of being able to choose.

Iyengar tells the story of a study where choice is removed:

“In a 1976 study at Arden House, a nursing home in Connecticut . . . scientists Ellen Langer and Judy Rodin manipulated the perception of control among residents aged 65 to 90. To begin, the nursing home’s social coordinator called separate meetings for the residents of two different floors.

“At the first floor’s meeting he handed out a plant to each resident and informed them that the nurses would take care of their plants for them. He also told them that movies were screened on Thursdays and Fridays, and that they would be scheduled to see the movie on one of those days. He assured residents that they were permitted to visit with people on other floors and engage in different types of activities, such as reading, listening to the radio, and watching TV. The focus of his message was that the residents were allowed to do some things, but the responsibility for their well-being lay in the competent hands of the staff, an approach that was the norm for nursing homes at that time (and still is). As the coordinator said, “We feel it is our responsibility to make this a home you can be proud of and happy in, and we want to do all we can to help you.”

Then the coordinator called a meeting for the other floor. This time he let each resident choose which plant he or she wanted, and told them that taking care of the plants would be their responsibility. He likewise allowed them to choose whether to watch the weekly movie screening on Thursday or Friday, and reminded them of the many ways in which they could choose to spend their time, such as visiting with other residents, reading, listening to the radio, and watching TV. Overall he emphasized that it was the residents’ responsibility to make their new home a happy place. “It’s your life,” he said. “You can make of it whatever you want.”

Despite the differences in these messages, the staff treated the residents of the two floors identically, giving them the same amount of attention. Moreover, the additional choices given to the second group of residents were seemingly trivial, since everyone got a plant and saw the same movie each week, whether on Thursday or Friday.

Here’s the result:

Nevertheless, when examined three weeks later, the residents who had been given more choices were happier and more alert, and they interacted more with other residents and staff than those who hadn’t been given the same choices. Even within the short, three-week time frame of the study, the physical health of over 70 percent of the residents from the “choiceless” group deteriorated. By contrast, over 90 percent of the people with choice saw their health improve. Six months later, researchers even found that the residents who’d been given greater choice—or, indeed, the perception of it—were less likely to have died.

The nursing home residents benefited from having choices that were largely symbolic. Being able to exercise their innate need to control some of their environment prevented the residents from suffering the stress and anxiety that caged zoo animals and lower-pay-grade employees often experience. The study suggests that minor but frequent choice making can have a disproportionately large and positive impact on our perception of overall control, just as the accumulation of minor stresses is often more harmful over time than the stress caused by a few major events. More profoundly, this suggests that we can give choice to ourselves and to others, along with the benefits that accompany choice. A small change in our actions, such as speaking or thinking in a way that highlights our agency, can have a big effect on our mental and physical state.

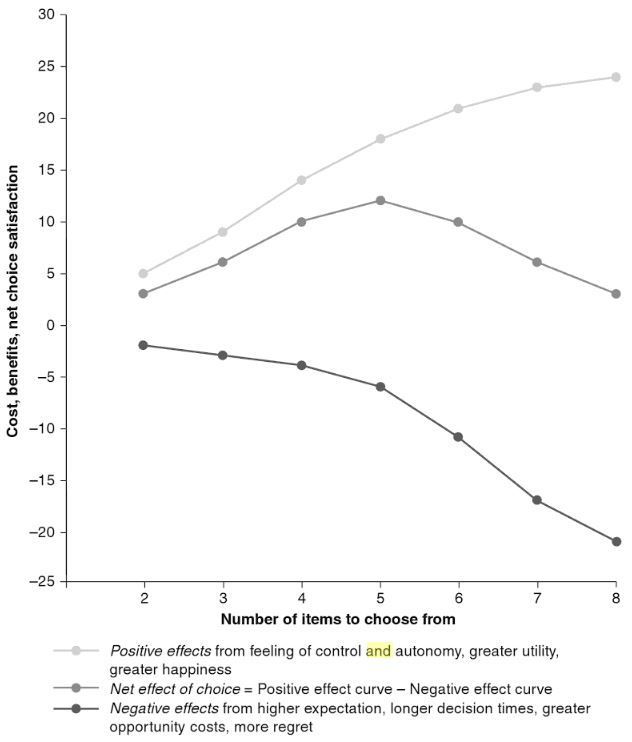

So if a single option—i.e., a lack of choice—is too restrictive, and too many options is “debilitating,” as we saw above, then what’s the optimal number of choices?

Here’s what we know:

- 6 choices is better than 24 choices. In the jam study mentioned above, 30% of customers who chose from 6 jams bought one, while only 3% of customers who saw 24 jams bought one.

- 4 choices is better than 30 choices. In another study, people who chose a piece of chocolate from 4 options were more confident in their decision that those who chose from 30 options.

- 5 choices is better than 32 choices. In a study of employees selecting retirement plans, 72% of employees chose a plan when 5 options were presented, while only 67.5% of employees chose a plan when 32 options were presented.

- 8 to 14 choices is better than 2 to 6 choices and better than 16 to 20 choices. In a study by Anvi M. Shah and George Wolford, and summarized in The Effect of Having Too Much Choice: “In their experiment, they offered participants the opportunity to purchase a black pen for a reduced price. The number of different pens to choose among was varied from 2 to 20 in increments of 2 pens. What they found was that for the lowest three assortment sizes of 2 to 6 pens, 46% of the participants purchased a pen. For the largest three sets between 16 and 20 pens, 33% purchased, while for the middle-sized assortments of 8–14 pens, the percentage of participants who purchased peaked at 70%.”

According to The Art of Choosing, “when people are given a moderate number of options (4 to 6) rather than a large number (20 to 30), they are more likely to make a choice, are more confident in their decisions, and are happier with what they choose.”

from Motivation: Biological, Psychological, and Environmental, 4th ed.

How to make the correct choice when you’re confronted with too many options

from Motivation: Biological, Psychological, and Environmental, 4th ed.

How to make the correct choice when you’re confronted with too many options

Unfortunately, we’re often in situations where we’re forced to choose from more than “a moderate number of choices.” What do we do then?

Iyengar compared two groups of Audi A4 buyers faced with a total of 144 choices in selecting their cars.

“One group of people first made their choices for the dimensions with the most options: interior and exterior color, which had 56 and 26 different options, respectively. From there they chose in descending order by number of options, ending with interior decor style and gear-shift style, which had only four options apiece.

“The second group encountered the same choices in the opposite order, starting with the ones with the fewest options and ending with the most.

“Although both groups ended up eventually seeing 144 total options across eight categories, the people who started high and ended low had a significantly harder time choosing.

“They started off carefully considering each option, but quickly became tired and went with the default option. In the end, they wound up paying 1,500 euros more for their cars (some of the defaults were more expensive than other options), yet were less happy with them compared to the people who went from low to high.”

To make better choices, you need fewer options.

And if you don’t have fewer options, you’ll need to take the options you do have and break them into manageable sub-categories and start with the least complex sub-category first.

There’s much more to learn about choice. I highly recommend Sheena Iyengar’s The Art of Choosing as a great introduction. If you’d like to hear about other great books, sign up for the book recommendations email.

Advertisements If you found this interesting, share it!