This article was first published to The Edge on November 9th 2017

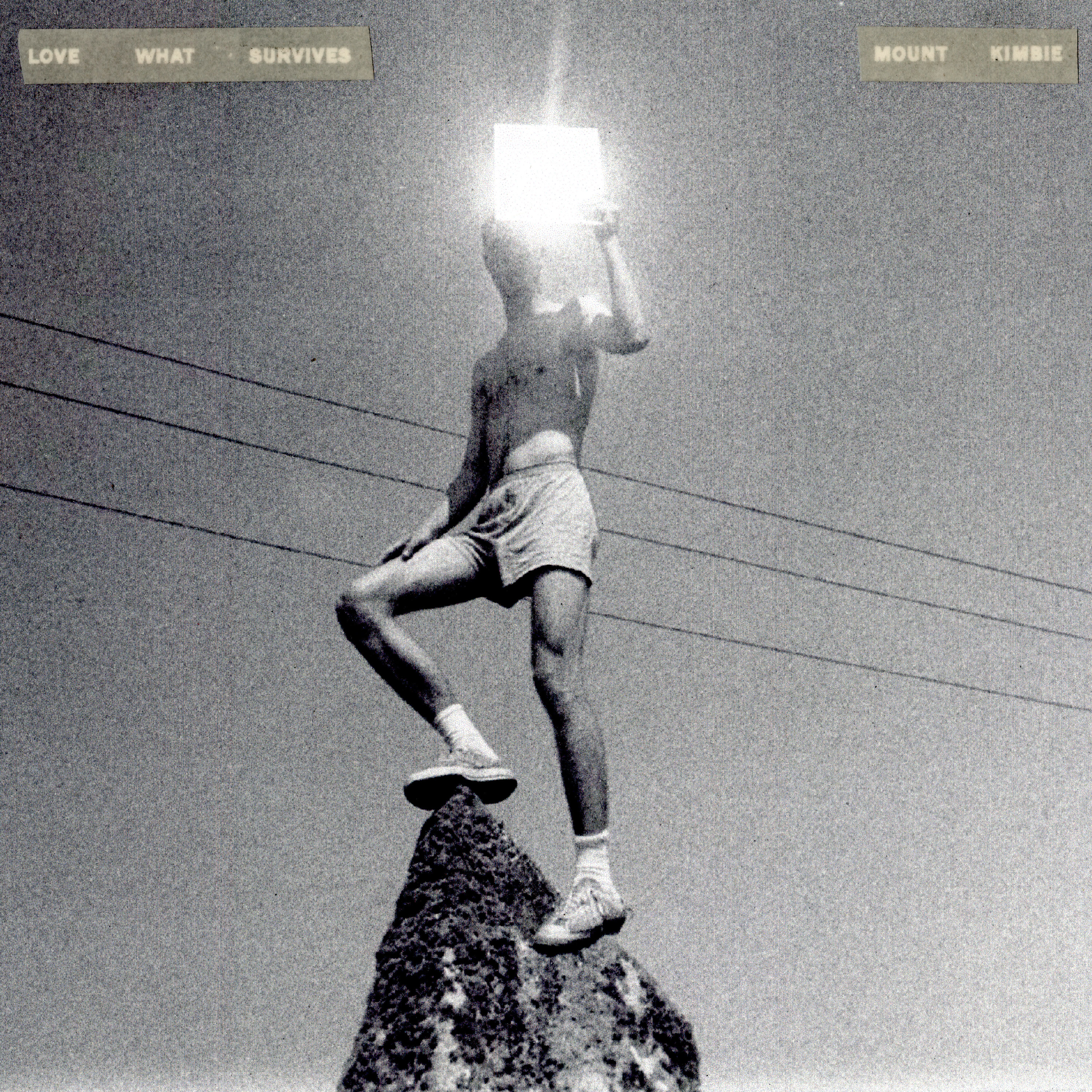

If you’ve been paying attention to The Edge this autumn, you’ll know that one of our favourite albums was the “Experimental-Indie” electronic music of Love What Survives. It’s the third-LP from the London-based duo of Mount Kimbie. Ahead of the duo’s end-of-year UK tour, we caught up with Dominic Maker, who spent the best part of last year living in LA, creating a transatlantic split with partner Kai Campos. However, that split was far from the disadvantage that it would appear to be, as we found out in the interview – along with how the pair have dealt with new collaborating experiences, and how they feel about their older music looking back.

How are the rehearsals going?

Good. This is the first time that we’ve got a sort of visual set-up behind us when playing. It’s the first time we’ve ever put any kind of money into the production. Which is taking a lot of time but [it’s] a lot of fun. We’re all set up in the room, and we’ve got our lighting guy sorting it out for us. So, it should be quite a different way of experiencing the show.

What sort of visuals?

We’re quite aware that we don’t want it to be almost a distraction, so if anything, it’s more kind of trying to set a bit of a mood for each of the tracks we play, and just to highlight certain areas of the set.

Did you do much sampling of found sounds on this record?

I think the only sample in the whole record was on ‘We Go Home Together’, that sort of gospel loop at the beginning of that track. But I think the more that I look back on how we’ve made this album, I think we’ve started to take the enjoyment we used to have from searching through found sounds and going out with field recorders and sampling other records, we [now]take the same pleasure from recording longer takes of stuff out of the equipment that we have. That’s really been the backbone of this album, seeing the potential in sitting there and playing around with an idea on a synthesiser, and then going back in and sampling, re-sampling from that.

What equipment are you playing with?

We’ve got a couple of new bits, a Korg MS20, and then we’ve also got the Korg Delta, quite a dry synthesiser. Kai’s more interested in that side of things, in the gear stuff, and I just love sampling, so I just go over what he’s done. We actually use both of those synths in the live set, and that’s been great. Because that’s been a major problem for us in the past, trying to replicate songs that were made entirely with samples and software, trying to replicate those in a live setting was always difficult for us. I think now, and the way the band’s set up is way more conducive to this record.

Do you feel like you’ve completely changed your live approach with the new record, even since last year’s playing with Andrea [Balency] and Marc [Pell]

Yeah, I think to me, playing live is now more exciting than it’s ever been, because we’re in a situation where we can even push forward with some of the tracks on the new record. We play around with them [more]. Working on new bits on a track, and also variations on the arrangement and stuff. It’s just fun, the way it’s been set up, Andrea and Mark are just fantastic additions and great people to be around. And it’s been great for me and Kai, y’know it pushes us two to be a bit more experimental on the live side.

How would you sell the sound of Mount Kimbie – whether it was this record now or the stuff you’d done previously?

I really don’t know because I got a cab to the rehearsal room today, and the cabbie said to me “[are you]going to work?” and I went “No, I’m going to go and play music”, and he goes “What kind of music do you make?” and I always say electronic, because it seems like the easiest way. But I don’t know because it’s difficult to assemble that in my own mind. It’s such a big mixture of loads of different influences and sounds and interests that I don’t know how to describe it. I suppose this record’s quite “Experimental-Indie” music, and a little more Pop leaning. Think we’ve always had that in the blood of the band, had that interest in Pop melody without going too far.

Do you think there are any specific artists, new or old, who are particularly good at remixing the rigidity of pop to make it interesting?

I think we listen to quite a bit of older music. Someone like Robert Wyatt is really important, because it’s got hooks that can get stuck in your head but pretty far out arrangements, and obviously Arthur Russell was a big influence on this album. It’s kind of taking that more, conventional pop melody with choruses and verses, but then with a very left-field approach. And I think that’s been a big interest of ours. We’ve also listened to a lot of older Soul music, some of that stuff that relied heavily on rhythm-box drum machines. You know, having that rigidity in the beat, and then fashioning a song out of that, based around the drums, was something that we’ve definitely been interested in, and I think that comes across on some of the tracks on this record.

Was there a specific choice to have less of your own vocals on Love What Survives than on Cold Spring?

Not really. A lot of the tunes we make are not spoken. We don’t mull over how we should do something, it didn’t feel right to do much of that on this record. And it’s great, because we’re fortunate enough to have James [Blake], Archy [Marshall aka King Krule], Mica [Levi] and Andrea [Balency] who sing a million times better than we do, so we just had them come in, and they were very much part of the writing process. It wasn’t like: “Here’s an instrumental, and then sing over it”; they really informed the way the tracks [that]they’re featured on came together. And yeah, I think it didn’t really feel right to sing too much. I like the track ‘T.A.M.E.D.’ because that’s me, Kai and Andrea all singing together, which I love, and that’s really fun when we’re doing it live. But we had a lot more going on instrumentally, and had a lot more interest in the instrumental side, so I think that vocals were an afterthought on our front.

You say they were really involved in the collaboration, so how does that change the work you and Kai did?

It was interesting because we hadn’t done that much of it. Obviously, we had Archy on the last record. But so little needed to be recorded from all of them because they were that good. And I think it was just more arranging around vocals that was a new challenge for me and Kai. And yeah, that was the thing, we wanted to give everyone the license to do whatever the hell they wanted to do, there was no direction in terms of vocal content, lyric content, or whatever. It was just “That’s where the song’s going to go, let’s just make what we can out of what we have.” I think that’s always been an approach that we like. We like stepping a little bit into the unknown, and working with people’s vocals is just another thing that we have very little experience with. And that’s what makes it exciting.

Between you and Kai how do you work separately, who starts the process off for a song?

I don’t know, we’ve always worked very differently depending on the record and where we’re at. I think I was way more into arranging a lot on this album and taking parts that Kai recorded and trying to work them into the arrangements. But then Kai became obsessed with the sound of those two synthesisers. We always get excited about playing each other’s stuff, because we don’t really sit in the room together and write an idea from scratch, ever. It’s mainly coming in and playing each other what we’ve been up to. Something that he wanted to throw away I would say “That’s brilliant, I can see something out of that, let me take care of it I’ll try and work it [into]something” and vice versa. There’s never been an assigned role as such for either of us, it’s always dependent on what we’re doing and where we’re at, and I love that. It’s one of the reasons why we’ve stayed together so long, it’s quite rare to have that unspoken connection with someone.

I assume [the transatlantic split]made the process quite different. What were you doing when you weren’t working together or trying to communicate with each other?

I was working a lot with James in LA, and Kai was – basically the main studio we’ve got is in London. So, I was spending a lot of time coming backwards and forwards between the two. It didn’t feel too different to how we’d work in the past, where we’d both be working separately and then come together a bit later down the line. I think it was if anything, a real positive, because it gave us quite a different perspective on things. Kai came over to LA and we had some good sessions there. And obviously at that point it was pretty early on when I’d moved there, so it was a completely new place for both of us. And that was great: we hired out someone’s studio, a tiny little room where we could bring any gear with us, any of our stuff. He had a really old drumkit in there and an electric piano, two things that neither of us have at home. It was great kind of, being out of our comfort zones and not relying on old habits. I think that session, although a lot of it didn’t get used on the album, it pushed us into a different place. I think that formed a lot of this record.

Do you think that there’s a central idea for you both that fed the album, or that has become the thing that most energises you when talking about it?

We wanted to do something that had a lot of energy in it. That wasn’t so… I dunno, I hate to say it but a lot of the stuff on the album were things that we genuinely hesitated [over]. We said, “This can’t be a Mount Kimbie song.” And that’s when we were like “Well there, that’s definitely going to be a Mount Kimbie song” because I hate the idea of feeling trapped by what you’d done before.

By your past identities?

Yeah, exactly. I suppose that energy of being a little bit like, “We might be pushing a little too far” was healthy, and it felt good, it felt liberating. It was like running away from home for a bit, which was exciting, I think that’s the main thing that we both had in our minds. We want to [put]the energy and the kind of life that we have, into the music more. There was more confidence that came across in the songs, whereas before we’d kind of flit around, change tempo, and change direction, completely change around in the middle of the track. Mainly almost feeling like you’re running away from yourself, that’s how I hear those old songs. I think with this new one, it’s got a bolder voice, that’s the most important thing.

Am I right in thinking that the synths you’ve talked about are more on the old side?

Yeah, I dunno when they were made, I think it was 70s, I’m probably wrong with that

Does that bring you more in line with artists that you mentioned like Robert [Wyatt] and Arthur Russell?

I definitely think that had an impact on choosing them, those pieces. I dunno, because they’re so bulky, they have so much character to them and they’re not easily manipulated. That was quite exciting to us, to use something like that that had so much of its own voice, that was very difficult to mould into your own. And just trying to take from that what we could, what sounded interesting to us. Also, the Korg Delta is built like a tank, and it sounds pretty dry and quite abrasive at times, but using something like that was exciting in itself because we’d had that. We had software before that we could just manipulate to however we’d want to, but this was quite unmanageable, which was fun.

Advertisements Share this: