It was not easy to explain to my business partner and to my clients my decision to spend two weeks in the Arizona desert with a Yaqui shaman at the height the television casting season—the busiest time of year. Regardless of the consequences to my career, I felt I had to make this journey. Since my cancer diagnosis a year earlier, my discernment process had switched from an “I can’t afford to” attitude to an “I can’t afford not to” reality.

A limited knowledge of Carlos Castaneda’s books had led me to expect a Yaqui Shaman to be mysterious, intimidating and unapproachable. Lench Archuleta, when I met him in February of 1999, was none of these things. He was a welcoming, down-to-earth, middle-aged man living with his second wife, Patty, and their infant son, Eli, in a modest two bedroom house on the edge of the Arizona desert.

Lench had served in the Vietnam War as a “tunnel rat.” He was assigned to search the underground tunnels that the Vietnamese soldiers built and to make sure they were abandoned and not mined or booby-trapped. Lench survived for a tour and a half because of, as he characterizes it, his intimate relationship with the earth and living things which he learned as a child from his father and grandfather.

Lench told me this story the first evening:

When he returned from Vietnam, Lench’s first wife told him that she wanted a divorce and that she was taking their three children to Minnesota to live with her family. Shortly after they left, his home and what was left of his possessions burned to the ground.

Lench called his father looking for sympathy. Who wouldn’t? He had lost everything.

After a moment of silence, his father asked, “Lench, what ear are you listening with?” Lench answered that he was listening with his right ear. His father directed him to take the phone out of his right hand, place it in his left hand and listen with his left ear. Lench did as he was told. “Can you still hear me?” his father asked. Lench said that he could. Then his father said, “Lench, walk to the window and tell me what you see.” Lench walked to the window. Then his father said, “Lench, put your hand on your heart.” And Lench did.

“Well, let’s see,” his father said, “Your ears are working. Your eyes are working. Your heart is beating. You walked to the window. You held the phone in both hands, so your hands are working. What’s the matter?”

Lench did not answer.

“Lench,” his father said, “You’ve forgotten the old ways. You’ve forgotten who you are. Go into the desert and don’t come back until you remember who you are.”

Before I retired to the guest room, Lench made it clear that he may or may not be able to help me. “There are some people I am unable to help. There are no guarantees.”

The next morning I dressed in clothes that I had carefully selected to protect me from the desert. Lench took one look at me and said, “We have to go to Wal-Mart”—an experience that up until that moment I had spent a lifetime conscientiously avoiding. Lench told me to buy shorts and sandals, clothing that would expose me to the desert.

On the drive back to the house, Lench admonished me, “You’re not paying attention. The desert is greeting you and you are oblivious.”

I had no idea what he was talking about.

We parked in front of the house and I started to get out of the car.

“Sit still and pay attention!” he commanded.

I finally noticed some birds sitting on a fence.

“Do you mean those birds?” I asked.

“They are doves. They have been following you everywhere. They waited for you in the parking lot at Wal-Mart. They want to welcome you to the desert.”

I changed clothes and we headed for the desert. I brought a backpack loaded down with water, sunblock, insect repellent, Band-Aids, and other “emergency supplies”. Each evening I removed a few items from my backpack so it would be lighter the next day.

As we drove into the desert, I was depressed by all the litter and garbage that lined the two-lane road. Lench told me to stop focusing on the garbage and pay attention to all of the life that surrounded us. As he drove, he pointed out hawks, roadrunners, coyotes, owls, rabbits, and even lizards. I looked as fast as I could but I missed almost everything. Lench explained that every animal and plant carries meaning, guidance, and spiritual direction to a Native American, and I must learn these things. As we drove into the desert, I began to feel like a child and Lench began to feel like a father. I knew Lench was going to teach me things my father never knew, never had any way of knowing. Among other things, Lench was teaching me to see the life rather than judge the garbage. I still need to be reminded of that from time to time.

Each day the desert became more alive to me and each day I was more filled with a sense of wonder. As Archie, the spirit of Lewis Mehl-Madrona’s grandfather had predicted, my soul loved the desert.

Lench is as comfortable in the desert as I am in my neighborhood. Once we reach the day’s destination, he strips to his shorts, takes off his shoes, picks up his staff and begins to walk on the earth as if we were on a lush carpet. The first day, Lench told me to take off my sandals and walk barefoot on the sand. I hesitated. (I seldom walk barefoot even in my own home.) “Don’t worry,” he said, “it’s too hot for snakes.” I froze in my tracks. Lench laughed. I did as he bid and began to walk barefoot, slowly, tentatively. “Are you afraid of your own, mother? Lie down. Let her love you.”

We returned to the desert every day. Sometimes Lench would leave me alone in the silence. Other times he would challenge me to do physical things—rock climbing and such that I had never attempted before. At night he instructed me in how to make my own medicine bag and rattle. Making the medicine bag and decorating the rattle were forms of prayer and meditation. He also directed me to make 405 prayer ties, small pieces of colored cloth wrapped with string. Each prayer tie contained a small pinch of tobacco. The prayer ties are strung together. Everything he had me do, he told me, was in preparation for rituals that would take place at the end of my visit. One of these rituals would entail sitting alone all night on top of a mountain. The string of prayer ties was to mark the parameters within which I must stay for the duration of the night. I had never even camped out in my backyard.

When it was too hot to be in the desert, we would visit Lench’s friends in town. These were not casual drop-ins. When Lench said, “Maybe you’ll meet . . .” what he meant was “these people are teachings I am presenting to you.” Each of them is a “two-legged” classroom. Each one offers you a “new way of seeing.” Each encounter will expose you to “models of blindness” which, if you pay attention, will reflect your own blindness. Over and over, Lench reminded me that nothing is what it seems. “Don’t ever assume that the person you meet today is the same person you met yesterday.”

On one of our excursions Lench took me to visit Grandfather Mountain, a marvel of rich red earth and stone. It looks like an artist’s studio where God creates stone and clay models of creation. As the sun casts light on the stones at different times of the day the mountain reveals creatures in the rock formations—an angel, a frog, a camel. The top of the mountain always looked the same—the face of an ancient Indian carved deep in the rock. It became a particularly sacred place for me and we returned there several times.

Three nights before I was scheduled to leave, Lench announced, “Tonight’s the night you spend on the mountain.” I was allowed to bring water and two blankets, one to sit on and one to wrap myself in plus the sacred objects I had prepared.

We parked at the bottom of a mountain. I followed Lench up to the top which overlooked a vast expanse of desert. He marked the parameters of the area with four sticks and together we strung the 405 prayer ties around them, enclosing the space. He instructed me to lay out the sacred objects in front of me. When I finished, he said, “You’re on your own. I’ll be waiting at the bottom of the mountain. I’ll come back for you in the morning.'”

I watched the sun set until the sky became black except for the stars. It got cold fast and I began to shiver—part from cold and part from fear. Every noise startled me. After what seemed like hours, the moon rose. It was a full moon, huge. It illuminated the mountain and I was able to see that most of the noises that startled me were coming from the prayer ties blowing against the brush. As cold, uncomfortable, and frightened as I was, I began to get very sleepy, almost as if I had been hypnotized. I woke with a start to find Lench and Patty standing over me. The moon had traveled halfway across the sky.

“You didn’t even hear us coming,” Lench said. “You must stay awake.”

They left. I got up and moved around within the boundaries of the prayer ties. I sat down determined to stay awake. A huge black owl settled on a rock barely a yard away from me. Lench had advised me to welcome whoever came to visit. I was terrified. The owl seemed almost as big as my torso. “Welcome,” I swallowed. The owl peered at me for what seemed a very long time and then departed as silently as it had arrived. As soon as it left I began to feel drowsy again as if I’d been drugged. I fell into a kind of stupor. I could see myself sleeping and hear myself snoring but could not rouse myself.

When I awoke the sun was up and a skunk was padding around the perimeter of my space sniffing the prayer ties. “Welcome,” I whispered very, very quietly. Two hawks were circling above me looking for breakfast. When the skunk had moved a safe distance away, I got up and stretched. I stepped outside of the prayer ties and looked over the edge of the mountain. Lench and Patty had lit a fire and were preparing breakfast. I called to them and Lench came up to guide me down. I confessed embarrassment at being unable to stay awake through the vigil. Lench told me not to worry, that my sleep was not an ordinary one. He thought the Star People had put me to sleep so they could work on me without my interference. “It’s the only way you could have slept through all that was going on.”

I have never had any experience of extra-terrestrials; however, when I stared at the stars in the pitch black sky, some of them were twinkling, others, it seemed, were observing me with unblinking eyes.

On my last night, we drove into Tempe. I wanted to treat Lench and Patty and Eli to a farewell “thank you” dinner. Lench ordered a potent tropical rum drink, the kind with a skewer filled with fruit and a little umbrella. It had not occurred to me that Lench drank alcohol. We hadn’t had so much as a beer the whole time I was there.

As he drank his cocktail, Lench told me a story about his father. He had spoken of his father and his grandfather many times during the past two weeks, always with a reverence and respect toward his elders that I have rarely heard among men.

This story was different. “One time my father got very drunk,” Lench began. “I was embarrassed and ashamed to see him behave that way in front of my brothers and sisters. (Lench is the oldest of seven children.) “When my father got up to go to bed, he knocked over a lamp and almost broke it. After my father left the room, I began to criticize his behavior to my brothers and sisters. Suddenly it got very quiet. I turned around and my father was standing in the doorway. He was not drunk. He said, ‘Lench, when are you going to learn not to believe everything you see?’ I never forgot that lesson.” This is the way Lench teaches, informally, through stories. I knew to pay careful attention. Lench tells stories the way magicians perform illusions. If you look away for a second, you’ll miss the trick.

Our server arrived with appetizers and Lench ordered another drink.

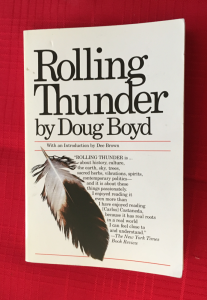

“I knew Rolling Thunder,” Lench said, beginning another story. “Do you know about Rolling Thunder?”

The name was vaguely familiar.

“There is a famous book about him. He was the last of the great medicine men. He could make it rain. He lived to be very old. Lewis (Mehl-Medrona) and I spent a weekend with him before he died. Sometimes he would call me on the phone. It was a great honor to be called by the last of the great medicine men. As Lench continued to speak of Rolling Thunder, he repeatedly emphasized that Rolling Thunder was the last of the great medicine man. “One day, just before he died, Rolling Thunder asked me, ‘Lench are you a medicine man?’ “No, Rolling Thunder,’ I said, ‘I’m just a man.’ Rolling Thunder laughed and said, ‘Me, too.’ It was the last time we talked.”

Over dinner Lench continued to talk, more than he had at any time during my stay. “People come to see me and want me to teach them what I know. They want to be healers, shamans and medicine men. They don’t understand. I’m just a man.”

Over dinner Lench continued to talk, more than he had at any time during my stay. “People come to see me and want me to teach them what I know. They want to be healers, shamans and medicine men. They don’t understand. I’m just a man.”

We returned to Lench’s home and I packed my things in preparation for an early morning departure. I told Lench I was looking forward to a good night’s sleep.

“While my body sleeps, I fly,” Lench said. “You should learn that.”

In the middle of the night I had a dream. The face on Grandfather Mountain, which sounded like Lewis’s grandfather, Archie, spoke to me. In the middle of the dream I suddenly awoke with severe chills and nausea. I rushed to the bathroom, vomited, and then sat down on the toilet feeling very faint. The bathroom clock said four a.m.

The Grandfather continued to speak even though I was now sitting in the bathroom with the lights on—wide awake. “If you are healed, you will never be the same. Can you accept that?” “Yes,” I said. “It will not be like it is now and it will not be like it was before you were sick. Can you accept that?” “Yes,” I said. “To be healed is to be like a man who has been struck by lightning and lived. Life is not the same. Can you accept that?” I went back to bed. I still had the chills but I was no longer nauseous. I wrapped myself in extra blankets. After a while, the chills stopped and I fell asleep.

I woke up the next morning feeling fine. Lench was waiting for me in the living room. When I told him what had happened, he said “I told Patty I should come in and check on you. I suddenly awakened at four a.m, too.” Lench asked me if I understood what all of this means. I said I did. “No, you don’t,” he smiled, “well, maybe just a little. Tell me what you understand.”

“You said people come to you because they want to know what you know, to become powerful shamans. You cannot teach them because what they really want is to become more than a man. It is hard enough to be ‘just a man.’ That’s what you were telling me about you and Rolling Thunder last night. In my dream the Indian was warning me that if I was healed, some people may treat me like I am more than ‘just a man.’ But I am just a man.”

“The creatures of the desert communicate with you because they know you know who you are—just a man. So a hawk is free to be a hawk with you; a lizard, a lizard; a cactus, a cactus. The desert cannot speak with you if you don’t know who you are. It won’t trust you if you desire to learn its secrets in order to be more than who you are. Adam wanted to be more than that. It is enough of an accomplishment to become ‘just a man.’ It is why God placed us here. To want to be “more than a man” is to be condemned always to be ‘less than a man’. This is what I understand.”

“You are a wise man,” Lench said. “I have a gift for you.” He went into his bedroom and quickly returned. “I never thought I would give this to anyone. Here– to replace the one you gave away at the sweat lodge with Lewis.” He handed me an eagle feather.

I would return to visit the desert and this wise, wily and loving teacher many times.

Lench can be contacted at: http://windspiritteaching.com/

{ Related post: Coyote Medicine }

“And the situation I am now in has been given me to change me, if only I will surrender completely to reality as it is given me by God and no longer seek in any way to evade it, even by interior reservations.” -Thomas Merton (1/25/63)

Advertisements Share this:- More