How do we face the harshest economic adversity, even as we understand that the cards are stacked against us to the point that hard work does not necessarily lead to success? What motivates us to continue when we realize that working just to stay afloat is impossible? When we’re born into a capitalist system that only benefits those who already have money or privilege — and even then on a system of credit that forces the wealthy to exploit the lower classes just to maintain their own inherited status — how do we push back in the face of such overwhelming hopelessness, unable to repair our own lives, much less fix the system?

These questions are impossible to answer, even for those of us who aren’t facing the dire and immediate existential crises of the poorest of our neighbors. I would never claim that fiction can give us complete or satisfactory answers to these questions, but I do believe strongly that fiction might work to help us better understand the most vulnerable in an unjust economic system. For those who are struggling with these questions on a daily basis, fiction might even function as both a life boat and a beacon, offering a refuge and at least the possibility of charting a course out of the abyss.

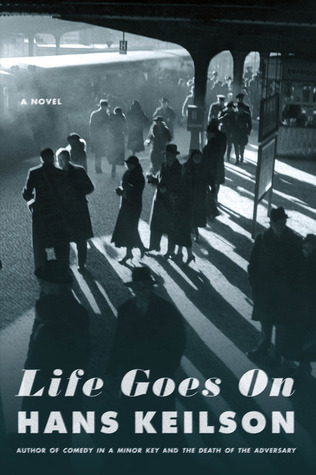

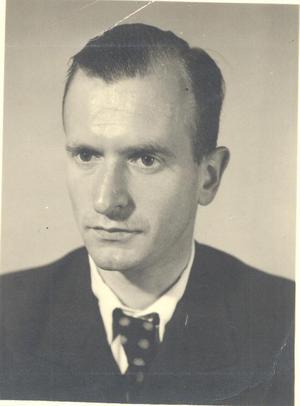

Hans Kelison

Hans Keilson’s highly-autobiographical novel — published when he was just 23-years-old in 1933 and burned by the Nazis a year later — is the story of one small family of merchants being slowly squeezed into financial ruin by the economic downfall in Germany between the wars. Albrecht (a thinly-veiled version of Keilson) and his mother and father struggle under crippling debt to borrow enough money to keep their small store stocked. Since their customers are also strapped for cash and borrowing on credit, the family finds themselves in the same dark hole as everyone else: they borrow items from bigger shops, selling them at a loss, and purchase items on credit that their customers in turn buy from them on credit, thus ensuring that no one can ever dig themselves out of the hole, no matter how hard they work. As this happens, those who already have enough money to survive continue to prosper — sometimes through shady means, such as burning their own businesses for insurance settlements — which only makes it more and more difficult for the impoverished workers to find jobs. Everyone purchases on credit, including those who are relatively financially secure, and no one has the money to pay back the loans, much less the interest.

The novel is ultimately about Albrecht’s transformation from naive schoolboy to college-educated working man, earning money as a struggling musician as he comes to embrace the leftist politics that might unite the working class against this endless cycle of exploitation and labor strife. It is a sobering, melancholy read that presents a realistic depiction of economic hardship, offering no brazen solutions or false hope. Indeed, the novel ends with Albrecht and his father continuing to struggle in Berlin, but finally acknowledging the need for solidarity with workers, as opposed to going-it-alone in the spirit of independent entrepreneurship, which had only succeeded in isolating the family from their community as everyone’s finances continued to sink, including their own. The message is clear: we are stronger when united, if only to help each other carry our shared burdens.

In front, at the head of the procession, is a solitary man, and the rest follow behind him in well-organized rows of four that swell to a larger and larger demonstration. Workers, the unemployed, impoverished middle-class citizens, students — women and men — all marching at the same pace, and even though the man in the first row doesn’t know the man in the tenth row, doesn’t even know who he is, they are marching together. A mighty will streams out from them, a united readiness: they know why they’re marching. — Hans Keilson

Even before the novel was banned and burned, the publishers required Keilson to change the ending to be more ambiguous so as not to stir the wrath of the burgeoning Nazi regime. As a result, the marching workers are not explicitly described as striking Socialists, but Keilson leaves enough for the reader to understand that even though the writer was censored, the workers won’t be: “they know why they’re marching.” So do the readers. And, apparently, so did the Nazis, who banned the book, anyway!

The novel stands as the quiet protest of a young writer who understands that literature has the capacity to document injustice and transform the attitudes not only of those who live through difficult times, but also the generations that follow. We can only begin to lift ourselves — and each other — by first sharing our stories. His novel is a living document that still speaks clearly to anyone struggling in the 21st century with employment, economic inequality, and social injustice. As Keilson wrote in his 1983 afterward: “Literature is the memory of humanity. Anyone who writes remembers, and anyone who reads takes part in those experiences. Books can be reprinted. The fact is, there are archival copies of books. Not of people.”

Keilson is grounded in a realistic hope to the very end, suggesting that books can only go so far in preserving memory. It’s up to those of us who are living to carry on the lessons and traditions of the men and women whose memories are preserved in literature. Their stories live not just in the printed word, but in how we share their experiences, burdens, and joys, and in how we take up their causes during our own lifetime, announcing our own “united readiness” to join the march.

Advertisements Share this: