Sunday 12 November 2017 marks the twentieth anniversary of the death of Steven Kitson. Steve was born in 1957 as the eldest child of the South African communists and anti-apartheid activists David and Norma Kitson. In the 1980s, he became a leading member of the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group (after it grew out of the Free Steve Kitson Campaign which had been formed to protest his own brief detention by the apartheid regime in January 1982).

We told much of Steve’s biography in a blog post written on the 15th anniversary of his death from cancer in 1997:

Steve was born in London; but, as an infant, returned to South Africa with his parents in 1959, when they decided to deepen their involvement in the anti-apartheid struggle. His father, a member of the second High Command of Umkhonto we Siswe (the armed wing of the ANC), was arrested in 1963 and sentenced to twenty years in gaol the following year. Along with his mother and sister, Amandla, Steve endured two years of constant police harassment in South Africa following his father’s imprisonment before Norma moved her young family to London. Each December, from the age of sixteen, he used the holiday period to return to South Africa to visit David.

On 6 January 1982, while visiting his father in gaol in Pretoria, Steve was detained by the South African authorities, accused of being an ANC courier and breaching prison security by sketching the institution. Steve was violently interrogated – tortured – during his detention. Norma and her colleague at Red Lion Setters, Carol Brickley (a member of the Revolutionary Communist Group), quickly mobilised everyone they could think of to demand Steve’s freedom. The Free Steven Kitson Campaign was a success and he was released after six days. Within hours of phoning London with news of his release, Steve’s aunt, Joan Weinberg (Norma’s older sister), was murdered in her flat in Johannesburg. With Norma and the children in London, Joan had been David’s most frequent visitor throughout his imprisonment. Her killers were never found; indeed, they were never sought.

During its brief existence, the Free Steven Kitson Campaign drew scores of new people into anti-apartheid campaigning for the first time. In order not to lose this momentum, it was decided to transform the campaign into the City Of London Anti-Apartheid Group. Steve played an active role in City Group over the years. On both the 86-day picket of the South African Embassy in 1982 and the Non-Stop Picket four years later, as well as many protests in between, Steve taught picketers South African liberation songs. He frequently performed with City Group Singers. For many years he was a member of City Group’s committee, often working tirelessly in the office on the group’s financial and membership records, as well as contributing to its political leadership. He used his software skills to develop a membership database for the group at a time when few comparable organisations could invest in such technology.

In our research, several people remembered the time and patience that Steve would invest during his picket shifts, explaining the history of South Africa, apartheid, and resistance to it. He was central to the political education of many picketers. Like other members of the Kitson family, Steve was sometimes targeted by the police, but was also prepared to risk arrest to defend the right to protest against apartheid. In that context, one of the other voices that attested to Steve’s caring personality came from a (now retired) police officer. She told the following story:

Weirdly one of my most abiding memories was of being on the picket one evening and a call for assistance from a colleague coming over the radio. There was a fight happening around the corner in the Strand. I remember leaving my post and running round to help out, having a bit of a roll around on the floor helping to arrest a drunken yob and then having to trot back to the picket as by right I shouldn’t have left it in the first place but some things would always take precedence. I was obviously out of breath, a bit pale and the after effects of the adrenaline had kicked in and my hands were shaking. Steven Kitson was on the picket that evening and after looking at me in a concerned fashion for a minute or two he came over and asked me if I was alright. I was really rather touched. You have to appreciate there was very little contact with the pickets, they didn’t talk to us and we didn’t to them unless it was to raise an issue. It was a very nice gesture.

To mark this anniversary, I wanted to post something new, that might help enrich this picture of Steve. So, I dipped once again into the two crates of his papers that still sit in my office. Two items from the files for 1984 intrigued me. They both serve as a reminder that, prior to his parents’ suspension from membership of the ANC and SACP, and City Group’s ‘disaffiliation’ from the national Anti-Apartheid Movement, there were high profile members of the ANC and SACP in London who were prepared to work closely with them.

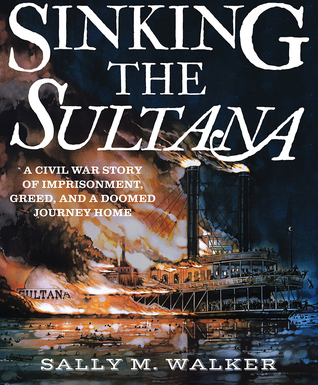

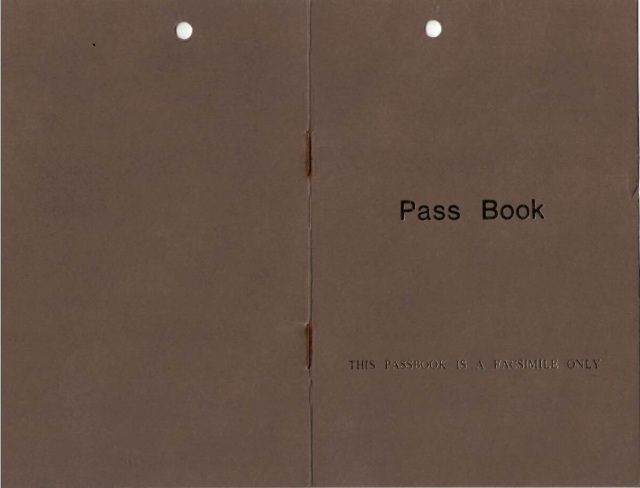

The first item is a facsimile of a Passbook that was produced for an exhibition about apartheid, The Signs of Apartheid, that was organised by the Greater London Council’s London Against Racism campaign in 1984.

What is perhaps most significant about this small brown booklet, that mimicked the internal passports used to control black workers (but, instead, contained information about apartheid), is the annotation inside it in Steve’s handwriting.

In Steve’s small, precise, script it states “given to me by Adelaide Tambo”. I take this both as a personal aide memoire of a small gift from a leading anti-apartheid campaigner who remained close to the Kitson family throughout; but also as political act – archiving evidence of Adelaide Tambo’s friendship against accusations that the Kitson family were ill-disciplined and outside the ANC fold.

The second item from Steve’s papers speaks to the centrality of music to his life and his political work. It is a photocopy of an image of Steve, the City Group Choir, and the South African cultural activist James Madhlope-Phillips. Having arrived in London from South Africa in the 1960s, Madhlope-Phillips’ home was be a key site of comfort and welcome for new exiles as they arrived in England; it was also a crucial early meeting place for ANC members in London before a formal office was established there. In the 1970s, he was central to the formation of the ANC’s cultural arm Mayibuye. Out of that contribution, he dedicated himself to teaching the freedom songs of Southern African liberation movements to progressive choirs around the world.

James Madhlope-Phillips (centre) with City Group Choir. Steve Kitson is third from left. (Source: Steve Kitson papers)

The card thanks Madhlope-Phillips for his ‘guidance’ and for leading the choir in song at a conference (as part of City Group’s contribution to month of action against apartheid in March of that year). Once again, Steve’s decision to keep a photocopy of the thank you card they sent to Madhlope-Phillips suggests a double motivation. It is, of course, a memento of a fun and energizing day of singing. But, it was also an insurance policy, recording a day of cooperation with a leading member of the ANC’s cultural wing, at a time when the relationship between City Group and the AAM (as well as between Norma Kitson and the ANC) was heavily under strain. Even so, that a high profile member of the ANC/SACP did cooperate with City Group at this time suggests that the strain on those relationships was not shared universally.

Many of the songs that were central to Madhlope-Phillips’ repertoire became favourites for City Group members – frequently led by Steve Kitson, both as part of the choir, but also more spontaneously on shifts on the Non-Stop Picket. So here, then is a wonderful recording of James Madhlope-Phillips leading Shosholoza. Sing along and remember Steve Kitson.

Advertisements Share this:

- More