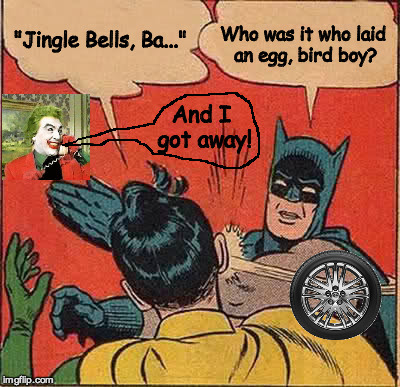

When I composed the bulk of my Batman memes, between January and March 2016, I knew very little of Batman except the 1960s TV series, which I loved and which defines the characters of Batman and Robin for me. (One of the memes uses the image of the Joker, as played by Cesar Romero

and another that of Burgess Meredith’s Penguin.) In preparing to write my book A Certain Gesture: Evnine’s Batman Meme Project and Its Parerga!, I thought I should rectify that and so I was happy to find a recent book had been published on the history and cultural significance of the various incarnations of Batman – The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture, by Glen Weldon. From that book, I learned that several of the themes I will deal with in my book are in fact pre-figured in the Batman corpus from the very beginning.

One such theme is a staple of contemporary philosophy of language: the nature and logic of proper names and how they differ from descriptions (definite descriptions like “the man who mistook his wife for a hat” – not to be confused with ‘The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,’ which is the proper name of a book – and indefinite ones like “a purveyor of fine wines”). One of my memes, which I won’t publish here, has Robin ask a question of Batman using the formulation “a Batman.” Batman replies, with a slap, that the question is ill-formed since “Batman” is a proper name and not a general expression that can be preceded by the definite or indefinite article. I learned from Weldon’s book that in the earliest appearances of the Caped Crusader, he is typically referred to as “the Batman” or “the Bat-Man”:

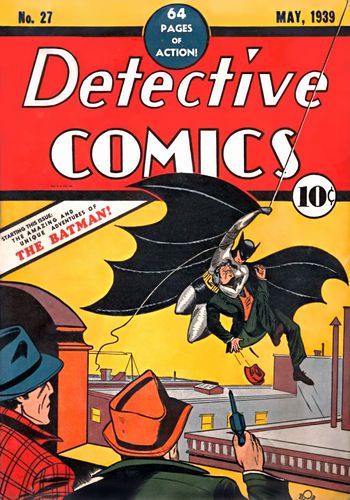

Cover of Detective Comics #27, the first appearance of Batman.

Cover of Detective Comics #27, the first appearance of Batman.

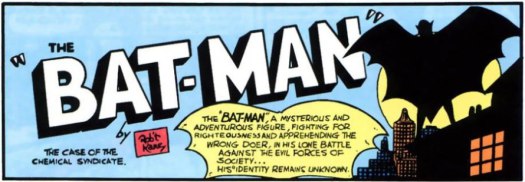

The first panel of Batman’s first adventure

The first panel of Batman’s first adventure

In other words, it treats “Batman” as a general term (emphasized by making its semantic decomposition in “Bat” and “Man” obvious through the hyphen when it appears as “Bat-Man”) and refers to Batman with the definite description “the Batman” rather than with a proper name. This usage persists and applies to other Bat characters too. Weldon notes the introduction of “the Batwoman” in 1956, who introduces herself in a way that leaves no doubt that we are not dealing with a degenerate description that is in fact a name (as with, say, with “The United Nations,” which has the form of a description but is really a proper name) since she uses “Batwoman” as part of an indefinite description: “I, too, will fight crime—I’ll be a BATWOMAN!” (Weldon, 60). Who know how many other Batwomen may be out there too!

Yet, of course, “Batman” is, or becomes, a proper name. There is no doubt of that. It loses the hyphen and it loses the article. (When and how would be an interesting study.) People address the character as “Batman” and refer to him as such. So, in the world of Batman, the relation between names and descriptions is already made an issue of. How does a descriptive phrase “the such-and-such” become a proper name “Such-and-such”? This is, in fact, not a phenomenon only in the Batverse. It must be how general terms like “smith,” “baker,” and “carter” become proper names “Smith,” “Baker,” and “Carter.” What are the logic and semantics behind this sort of change?

Advertisements Share this: