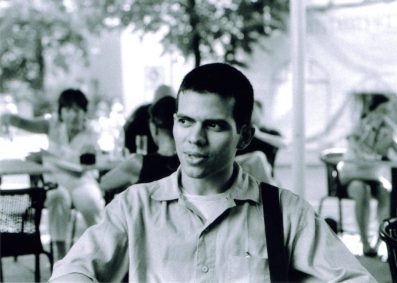

Like mustard, exile comes in many shapes and flavours; whether as a form of protest, voluntary, politically motivated, temporary or internal, there is always something tangy about it, often something sharp. That is precisely what Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles’s fiction is like: sharp and bold and refreshing, a pungent shot of vitality dilating the membranes of your congested nasal cavity as he depicts with insightful accuracy the anxiety and the longing, the risk and expectation, the inherent contradictions, that assail a generation of Venezuelans obsessed with the prospect of leaving. Once the bountiful haven of the many (Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Dominican, Colombian, you name it) who fled poverty (or fascism, or guerrilla warfare, or any other popular scourge cultivated in recent times), Venezuela has for decades reversed its role in global migratory patterns, feeding an abundant flow of its own disaffected children (ever the land of the plenty, Venezuela is indiscriminately rich even in its distribution of misery) into the already vast ocean of the world’s diasporas.

Sánchez Rugeles is one of the many economic migrants who have chiselled their way out, north or south, no matter, of the clamorous disaster that is Venezuela’s twenty-first century socialism, a member of that no longer select and rather dubious group who, like me, packed their bags and drew the line this side of Caracas. More than a classification, this gloss stands as an oblique introduction to the theme that concerns his first two novels, as narratives of exile.

The former novel, Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul, propelled Eduardo to national stardom by winning the short-lived Latin American Literary Prize Arturo Uslar Pietri, and immediately resonated on a segment of the population much neglected by the country’s literary establishment: young adults in their late teens, transitioning from school to university. In Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul Sánchez Rugeles speaks to these adults-in-the-making not from the position of strength and superiority of serious intellectuals or from the fascinating la-la land of fantasy but rather from the infirm and unapologetically fickle nature of their own actions. Indeed, he shows a preoccupation that verges on the anthropological as he records accurately and vividly the speech of young Venezuelans, slang and Anglicisms entwining in the formulation of an adolescent lingo that seems to partake in a universal pool of self-importance and that renders it equally irritating across cultures and regardless of the language. Placing his protagonists – and their pubescent parlance – centre stage, the author builds Venezuela’s modern-day response to Romeo and Juliet: the story of a doomed yet momentous romance between Eugenia Blanc and Luis Tévez, who are forced to overcome not the grudge held by their respective families against each other but rather the overriding sense of defeat and lassitude that, like a field flooded by a surge of groundwater, engulfs everything and everyone in the country.

Interested only in the rebellious act of not conforming, Luis makes his unorthodox way into the life of Eugenia, whose notions of love and friendship become irreversibly skewered as she grows closer to him and his gang of outcasts. Unafraid to engage with conventional structures, Sánchez Rugeles introduces a mammoth (in Venezuelan terms) 700-kilometer road trip to recreate the troubled courtship and inner journey of his young characters. In search of Eugenia’s long-lost grandfather, who by virtue of being French holds the key to her escape from the prison that is Venezuela, Luis, Eugenia and Vadier, a common friend, travel half the country listening time and again to an old Bob Dylan tape. Throughout the text Sánchez Rugeles reproduces brief snippets of lyrics from different songs – not only Dylan’s – to encapsulate the essence of the moment. To Eugenia’s exasperation, “Visions of Johanna” is by far the most played song in Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul’s soundtrack, as Luis prophetically emphasises the connection between Dylan’s lyrics, beat literature, Eliot’s verse and Gehenna, the Jewish equivalent to hell. “Can’t you see, princess, this is poetry right here”, Luis patronises Eugenia, as they exchange notes on their favourite songs.

Interested only in the rebellious act of not conforming, Luis makes his unorthodox way into the life of Eugenia, whose notions of love and friendship become irreversibly skewered as she grows closer to him and his gang of outcasts. Unafraid to engage with conventional structures, Sánchez Rugeles introduces a mammoth (in Venezuelan terms) 700-kilometer road trip to recreate the troubled courtship and inner journey of his young characters. In search of Eugenia’s long-lost grandfather, who by virtue of being French holds the key to her escape from the prison that is Venezuela, Luis, Eugenia and Vadier, a common friend, travel half the country listening time and again to an old Bob Dylan tape. Throughout the text Sánchez Rugeles reproduces brief snippets of lyrics from different songs – not only Dylan’s – to encapsulate the essence of the moment. To Eugenia’s exasperation, “Visions of Johanna” is by far the most played song in Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul’s soundtrack, as Luis prophetically emphasises the connection between Dylan’s lyrics, beat literature, Eliot’s verse and Gehenna, the Jewish equivalent to hell. “Can’t you see, princess, this is poetry right here”, Luis patronises Eugenia, as they exchange notes on their favourite songs.

Inevitably, the end of the adventure also threatens to spell the end of the aura of magic that has grown around their relationship. Back in Caracas things look set to fall into a routine of normality, until it becomes apparent that Luis too is confronted with visions of hell no matter where he is, no matter where he goes. This is where the short novel really comes together, as the melancholy undertow that recurrently pulls its head out from the juvenile reaches of the narrative is finally allowed to blossom into the full dimension of Luis’s tragic fate. As the final episodes unravel and the direction of the story becomes clear, Sánchez Rugeles’s delightful style takes control, leaving his characters’ dialect far in the distance and branding the novel with the seal of his inventive prose.

The outstanding feature of Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul, however, is the remarkable cast of secondary characters Sánchez Rugeles conjures up in just over 200 pages, from the bipolar Vadier to Eugenia’s pusillanimous father, or the impudently wasteful clique of Chávez supporters from whom the three travellers steal a case of Johnnie Walker Blue Label whisky, a powerful and accurate portrayal of Venezuela’s society in all its splendour.

Remarkably, when Sánchez Rugeles entered the Latin American Literary Prize Arturo Uslar Prieti in 2010 he intended to do so with a different novel, Transilvania Unplugged. Then the story of Eugenia Blanc and Luis Tévez monopolised his mind, to the point where he was able to put it together in time to submit both stories.

If Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul is ostensibly the tale of a girl’s efforts to leave the country, Transilvania Unplugged follows the erratic journey of two young professionals already removed, albeit only temporarily, from the sordid reality of day-to-day life in Caracas. Josep Antoniu Galleti Calinescu is a struggling journalist whose exiled Romanian family sought refuge in Venezuela in the days of Ceausescu. Hoping to hit upon the perfect formula to write a travel book that would allow him to claim a lucrative international literary prize, Josep Antoniu travels to the land of his forefathers to unearth family secrets that ultimately lead him through a labyrinth of intrigues to the darkest episodes in the history of Romanian politics. Meanwhile, his friend Emilio Porras, infinitely sceptical of both Josep Antoniu’s plan and writing skills, profits from an EU initiative to promote cultural exchanges in the city of Sibiu, soon to be Europe’s capital of culture.

If Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul is ostensibly the tale of a girl’s efforts to leave the country, Transilvania Unplugged follows the erratic journey of two young professionals already removed, albeit only temporarily, from the sordid reality of day-to-day life in Caracas. Josep Antoniu Galleti Calinescu is a struggling journalist whose exiled Romanian family sought refuge in Venezuela in the days of Ceausescu. Hoping to hit upon the perfect formula to write a travel book that would allow him to claim a lucrative international literary prize, Josep Antoniu travels to the land of his forefathers to unearth family secrets that ultimately lead him through a labyrinth of intrigues to the darkest episodes in the history of Romanian politics. Meanwhile, his friend Emilio Porras, infinitely sceptical of both Josep Antoniu’s plan and writing skills, profits from an EU initiative to promote cultural exchanges in the city of Sibiu, soon to be Europe’s capital of culture.

Desperately and undiscerningly looking for their ticket out of Caracas, Emilio and Josep Antoniu get caught in an even more perilous and cranky spiral of usury, incest and people trafficking which has the enigmatic figure of Luzny Hervasi at its core. Luzny’s character is a thing of beauty: once upon a time the personal pianist of the Ceausescus, the old man, mangled by elephantiasis, now lives a secluded life in Sibiu, where under a new name he still occasionally plays at a bar. That is where Emilio meets the pianist everyone seems to know by the name of Carol. Meanwhile, Josep Antoniu’s inquest into his family’s ordeal puts him at the mercy of a ring of conspirators whose main concern is to find Luzny. Comparing notes on their respective adventures via email, Emilio comes to understand that Luzny and Carol are one and the same person – by then, however, Josep Antoniu has gone missing, and in the process of finding him Emilio will also be lost without trace.

Like Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul Sánchez Rugeles’s second novel features an impressive cast of characters, but while in his previous work this gives substance to the context, in Transilvania Unplugged each of the secondary characters renders the story more and more freakish. To the reader, not only is everyone foreign in this novel (even Emilio and Josep Antoniu are foreign, for they are Venezuelans in Romania), they are all emphatically outlandish, much like the story itself. In this sense, Sánchez Rugeles’s greatest accomplishment is to hold the tale together tightly enough to keep the reader’s attention. Structure plays a central role in this balancing act, and the author’s forays into the world of modern communication, continuously reproducing the two friends’ emails to each other, creates an architecture that is reminiscent of the epistolary origins of the novel. This exchange, combined with a lively and sensitive narrator, are the tools that enable Sánchez Rugeles to control the pace of the narrative with the ease of a flea circus master, manipulating the reader into taking part in the subtle game of hide and seek that lies at the core of any crime novel.

After all, Transilvania Unplugged is to all effects and purposes a crime novel with the classic aesthetic of a hard-boiled film noir, spiked here and there with self-deprecatory humour, an element of parody and a generous dose of the Venezuelan telenovela to it – a complex and entertaining pastiche.

Though drastically different, Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul and Transilvania Unplugged both boil down to the same premise: a (physical) journey which, for very different reasons, ultimately carries disastrous consequences. Sánchez Rugeles’ obsession with escaping Venezuela is not only symptomatic of a generation which has come to regard the future as a foreign commodity, it is clearly also an expression of his own condition as a voluntary exile of his country. In his pairing of this irrepressible longing with the tragic dimension that shapes his novels, however, he has formulated – consciously or otherwise – the frame of mind developed, after decades of disillusionment, failure and crime, by the average Venezuelan. Once so optimistic, so nonchalant, wasteful and generous in equal measure, Venezuelans have come to accept that if the proverbial Murphy has a corporeal existence, he has undoubtedly moved to their country, where his is the one law enforced indiscriminately.

Though drastically different, Blue Label / Etiqueta Azul and Transilvania Unplugged both boil down to the same premise: a (physical) journey which, for very different reasons, ultimately carries disastrous consequences. Sánchez Rugeles’ obsession with escaping Venezuela is not only symptomatic of a generation which has come to regard the future as a foreign commodity, it is clearly also an expression of his own condition as a voluntary exile of his country. In his pairing of this irrepressible longing with the tragic dimension that shapes his novels, however, he has formulated – consciously or otherwise – the frame of mind developed, after decades of disillusionment, failure and crime, by the average Venezuelan. Once so optimistic, so nonchalant, wasteful and generous in equal measure, Venezuelans have come to accept that if the proverbial Murphy has a corporeal existence, he has undoubtedly moved to their country, where his is the one law enforced indiscriminately.

Times are hard in Venezuela, and the outlook is bleak, but perhaps precisely because of this more and more interesting, accomplished, urgent literature has emerged from the country over the past decade than in living memory. To those experiencing the monstrous dimension of the country’s present predicament this will come as no consolation, but there is an edge to contemporary Venezuelan literature – there is an edge to Venezuela – that is making it stand out in the literary sphere where it has rarely been acknowledged in the past.

Published by Minor Literatures on December 19, 2016

Advertisements Share this: