I didn’t grow up eating a lot of seafood. My mother was from rural south Texas, the product of a working mother who didn’t pass along a lot of homemaker’s knowledge. Her idea of dinner began with opening a can and ended with margarine on white bread as a side dish.

I didn’t grow up eating a lot of seafood. My mother was from rural south Texas, the product of a working mother who didn’t pass along a lot of homemaker’s knowledge. Her idea of dinner began with opening a can and ended with margarine on white bread as a side dish.

My father was a competent English cook but rose to the occasion only for Christmas and Easter. A leg of lamb or roast beef and Yorkshire pudding were his comfort zones. As a consequence, my first introduction to octopus was when I had to break it down and poach a batch in court bouillon as a grown up poissonnier at a Bob Gourmand restaurant in Manhattan.

I knew that octopuses could solve problems from watching David Attenborough documentaries and youtube videos of these escape artists unscrewing jars. I removed their beaks, separated their arms into portions and poached until tender. But I would ask my Sous to taste them as I could never bring myself to judge my own cooking results.

I am an avid reader and was recommended The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness by Sy Montgomery by a librarian friend. Sy’s book was a love story, an ode to the personality of a short lived but utterly fascinating octopus named Athena. It made me continue to wonder at the completely alien way in which the octopus ‘sees’ the world- through eyes that developed independently of our own mammalian ones, through ‘smelling’ by touching, their 500 million neurons suffused throughout their limbs rather than bunched in a centralised brain like our own.

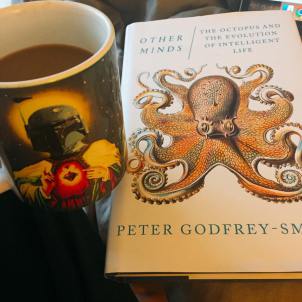

I picked up Other Minds in London at Daunt Books. [One of my favourite books shops in the world, Daunt is an original Edwardian bookshop with long oak galleries and gorgeous skylights in Marylebone High Street, specialising in travel literature but with staff selections that are mind-blowing in diversity.] I am only a third of the way through the book but this passage hit me:

“Imagine a jellyfish-like animal shaped like a dome, with a smooth underneath. One nervous system evolves on the top, and tracks light, but not as a guide to action. Instead it uses light to control bodily rhythms and regulate hormones. Another nervous system evolves to control movement, initially just the movement of the mouth. And at some stage, the two systems begin to move within the body, coming into new relations with each other. Arendt sees this as one of the crucial events that took bilaterians forward in the Cambrian. A part of the body-controlling system moved up toward the top of the animal, where the light-sensitive system sat. This light-sensitive system, again, was only guiding chemical changes and cycles, not behaviour. But the joining of the two nervous systems gave them a new role.

What an amazing image: in a long evolutionary process, a motion-controlling brain marches up through your head to meet there some light-sensitive organs, which become eyes.”

If that doesn’t grab you and shake you a bit, you need to wake up your inner child. How does the octopus see its world? They have been known to shoot water at the faces of people that ‘taste’ like cigarette smoke. They have shot out the lights above their tanks out of what seems to be sheer annoyance. They have escaped their tanks, walked casually across a lab, helped themselves to dinner by eating a neighbour, only to wander back to their own tank with the ‘keepers’ none the wiser. Basic instinct? Perhaps, but done with unmistakable style and something I would myself do in the same circumstance,

Honestly, I just won’t eat something that shares my sense of humour.

Like this:Like Loading...