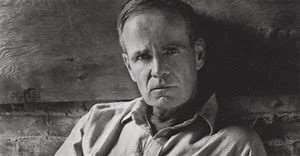

Note: Rather than a polemic against my nation’s punitive society, reflected clearly enough in our benighted immigration policy, our broken justice system, our mad rush to ecological devastation and/or nuclear annihilation, our increasingly unequal economic regime that punishes our humanity and rewards selfishness and greed – need I go on? – rather than that, let me share a page from my journal (Oct. 3, 1999): an extended meditation on Cormac McCarthy’s “Border Trilogy” (All the Pretty Horses; The Crossing; and Cities of the Plain).

Note: Rather than a polemic against my nation’s punitive society, reflected clearly enough in our benighted immigration policy, our broken justice system, our mad rush to ecological devastation and/or nuclear annihilation, our increasingly unequal economic regime that punishes our humanity and rewards selfishness and greed – need I go on? – rather than that, let me share a page from my journal (Oct. 3, 1999): an extended meditation on Cormac McCarthy’s “Border Trilogy” (All the Pretty Horses; The Crossing; and Cities of the Plain).

Martin Luther King, Jr. : “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

It is my hope, as I reflect again on this classic American literature, with its austere yet not unhopeful vision, that the worst of whatever ill destiny beckons humanity today might still be averted. May life continue, for our children and grandchildren, in something resembling its usual patterns – its arc still bending slowly toward mercy and justice, however erratically and impossibly in the seemingly indifferent universe we inhabit.

While what follows does necessarily contain some spoilers, I can only suggest the wealth of detail that has made it, for me, such essential reading. I offer it in the spirit of the best of what we call (not pejoratively, I hope!) “literary criticism.”

*

These three novels, as I have already noted, comprise McCarthy’s “Border Trilogy.” The first volume, which I have read three times now, remains in my heart the most beautiful and perfect, though this latest re-introduces that original hero in an equally compelling story. Volume two introduces another recurring hero, the only one, as it turns out, who will survive into the new millennium where we last see him. As a series these novels constitute, in my estimation, the elevation of the genre “western” to serious literature that will stand the test of time and any comparison to classics of any time and place.

These three novels, as I have already noted, comprise McCarthy’s “Border Trilogy.” The first volume, which I have read three times now, remains in my heart the most beautiful and perfect, though this latest re-introduces that original hero in an equally compelling story. Volume two introduces another recurring hero, the only one, as it turns out, who will survive into the new millennium where we last see him. As a series these novels constitute, in my estimation, the elevation of the genre “western” to serious literature that will stand the test of time and any comparison to classics of any time and place.

These are not happy stories. Their central themes concern violence and love and loss, perhaps primarily loss. And yet these are stories that, without the slightest touch of sentimentality, even as they are wrenching out your heart along with any last illusions you might have entertained that so-called “happy endings” are generally possible, have nevertheless enriched your heart in a way you wouldn’t want back for any of those illusions. And it is not, for all of its brutal darkness, a vision of humanity that is entirely bereft of hope. For every vision of senseless and hateful violence and betrayal, for instance, there is a counteracting vision of human goodness, even if it is of the sort that doesn’t prevail in historical-political terms.

The view of Mexican history and society that emerges, for instance, is nothing at all if not destructive, yet the generosity and open-heartedness of the common Mexicans encountered (the poorest and least society-bound of those) is everywhere evident. And this affects our heroes’ judgments of the world at least as much as the acts of violence do. It is this aspect of the novels that ultimately redeems that violence and supplies the reader with that modicum of hope that is still present through so much despair. For living, after all, despite all of its very real and inescapable disappointment, is not something we are generally anxious to be rid of.

All the Pretty Horses tells the story, primarily, of John Grady Cole, a young Texan cowboy with a great love for horses and at least as soft a spot for women. At age sixteen, after the death of his grandfather and the loss of the family’s ranch, he goes off with a friend to try his fortunes in a still more rugged Mexico. This takes place in roughly the late ’40’s (or early ’50’s), post-World War II, as the old ways on his Texas prairies are being lost. As he and his friend cross into Mexico, they are joined up by an even younger and more impetuous runaway, who ends up bringing them to considerable grief and himself to a desert execution. The story that really takes our heart like no other, though, involves John Grady’s passionate love affair with the daughter of the owner of the hacienda he and his orginal buddy work on for awhile.

All the Pretty Horses tells the story, primarily, of John Grady Cole, a young Texan cowboy with a great love for horses and at least as soft a spot for women. At age sixteen, after the death of his grandfather and the loss of the family’s ranch, he goes off with a friend to try his fortunes in a still more rugged Mexico. This takes place in roughly the late ’40’s (or early ’50’s), post-World War II, as the old ways on his Texas prairies are being lost. As he and his friend cross into Mexico, they are joined up by an even younger and more impetuous runaway, who ends up bringing them to considerable grief and himself to a desert execution. The story that really takes our heart like no other, though, involves John Grady’s passionate love affair with the daughter of the owner of the hacienda he and his orginal buddy work on for awhile.

Later, after being taken prisoner for that indiscretion and for their connection with Jimmy Blevins, after witnessing at some distance his dreadful death, after a brutal stint in a Mexican prison, John Grady meets up one last time with that lover and asks her to come to his country with him, promising (as we cannot doubt he would have attempted) to protect her and stay with her alone. My dad, who shared my initial enthusiasm for this book, told me that he was broken-hearted when, despite loving him, she would not go. In the end, John Grady engages in a dramatic gunfight to retrieve all of his own and his former companions’ horses (the other friend has returned home already by bus, from prison) and narrowly escapes death by gunshot, as he’d previously escaped it by knife wound in prison, before slipping back across the border. It’s a supremely heart-rending and beautiful story.

The Crossing tells the story of Billy Parham, who just slips across the border from New to Old Mexico on a quixotic quest (he is also about sixteen at the time) to return a pregnant wolf that has been hunting his father’s cattle and that he has trapped. This tale commences prior to our involvement in World War II, in the early ’40’s, so when he and John Grady Cole meet up for volume three, he is several years his senior. While on my first reading of this novel back in ’94 or ’95 I did not like it as well as the first, my appreciation for it has certainly deepened with this second reading. In any case, it is worth the price of the book just for that opening melody with boy and wolf, which stretches on for over a hundred pages and ends with boy disillusioned by the brutality of men and what he has to do just to bury that poor animal with its unborn pups in its native mountains.

The Crossing tells the story of Billy Parham, who just slips across the border from New to Old Mexico on a quixotic quest (he is also about sixteen at the time) to return a pregnant wolf that has been hunting his father’s cattle and that he has trapped. This tale commences prior to our involvement in World War II, in the early ’40’s, so when he and John Grady Cole meet up for volume three, he is several years his senior. While on my first reading of this novel back in ’94 or ’95 I did not like it as well as the first, my appreciation for it has certainly deepened with this second reading. In any case, it is worth the price of the book just for that opening melody with boy and wolf, which stretches on for over a hundred pages and ends with boy disillusioned by the brutality of men and what he has to do just to bury that poor animal with its unborn pups in its native mountains.

“Doomed enterprises,” we read at the commencement of part two, as he has just buried it, “divide lives forever into the then and the now,” and indeed that is the tone of this story from then on: of resignation and despair. Billy goes home, eventually, only to discover his father and mother murdered, his horses stolen, his brother (age 14) orphaned. He and Boyd cross back into Mexico in pursuit of horses. In the end, they retrieve the horses, but Boyd is almost killed by gunshot and, after being nursed back to health, leaves Billy and runs off with a poor Mexican girl who becomes his sweetheart. Billy crosses the border again, tries to join the army and is rejected because of a heart murmur, works for awhile on ranches and then goes back in search of his brother who has disappeared into the mists of legend and song, where he and his bandit girlfriend have merged with others in a popular corrido. In the end Bill returns home bearing his brother’s bones, much as in the beginning he’d come to Mexico with a wolf – and then had to bury it.

In Cities of the Plain, Billy and John Grady are both working on the same ranch outside of El Paso, Texas, halfway between their separate starting places. In the opening scene, Billy is introducing the younger John Grady to a whorehouse in El Paso’s twin city, Juárez, Mexico. John Grady, while not wanting to approach her with the older men present, sees the girl he falls in love with. Perhaps she reminds him, at this moment, of the rancher’s daughter, but in the end it is she herself that he loves. He catches up with her, later, in another establishment, and he makes love to her there and learns that she returns his affection. He plans to marry her and almost sweeps her away but for the betrayal that necessarily befalls.

In Cities of the Plain, Billy and John Grady are both working on the same ranch outside of El Paso, Texas, halfway between their separate starting places. In the opening scene, Billy is introducing the younger John Grady to a whorehouse in El Paso’s twin city, Juárez, Mexico. John Grady, while not wanting to approach her with the older men present, sees the girl he falls in love with. Perhaps she reminds him, at this moment, of the rancher’s daughter, but in the end it is she herself that he loves. He catches up with her, later, in another establishment, and he makes love to her there and learns that she returns his affection. He plans to marry her and almost sweeps her away but for the betrayal that necessarily befalls.

Prior to that, there is the tenderness of his preparations of the country cottage that he will take her to, and all the tenderness of his attention to her. In the end, though, they are betrayed and she is murdered. When he discovers her random body in the morgue (the tale of how she came to this captivity in a Ciudad Juárez brothel is horrible and pathetic), he goes almost mad with grief, then returns to either kill or be killed by the brutal slave trader who had her killed. In the end, after a battle that rages on for several pages, he kills the overconfident assassin and then slips off, it turns out, to also die from his own wounds. He dies as his older friend Billy Parham comes to his rescue, that closing image (prior to the epilogue) of Billy, grief stricken at the loss of a second little brother, carrying him across a Juárez intersection just as a Mexican woman is preparing to cross with a group of school children in their blue uniforms, is truly wrenching.

In the epilogue, Billy goes on to further wanderings and solitude, ending up at the beginning of the second millennium (year 2000 or 2001?) where he meets another wanderer who tells a strange and lengthy parable that winds up being, I rather think, the author’s transparent meditation on the nature of memory and stories and their various levels of truth. That part to me was puzzling and disorienting; I found myself agreeing with the character Mr. Parham, who says to his interlocutor at one point: “I think you got a habit of makin things a bit more complicated than what they need to be.” There was some meat there, no doubt, such that I might puzzle over to more effect on a future reading, yet perhaps the story might just as well have ended with the spare account of the older Billy Parham’s wandering, before and after that strange encounter.

The closing scene, less dramatic than that of him bearing John Grady’s dead body from a Mexican alley, is deeply moving for what it says to the more common disillusionments of all our lives, disillusionment met with still a touch of the sweetness of all of that living. In it the old man, who should have died years earlier of a murmuring heart but is left instead to remember those who died in his place, has taken up his winter’s residence with a family that gave him a place to sleep not unlike the place he had slept last in his parents’ home. He awakes from dreams of Boyd and is comforted by the woman of the house, who then asks him about Boyd.

Boyd was your brother.

Yes. He’s been dead many a year.

You still miss him though.

Yes I do. All the time.

Was he the younger?

He was. By two years.

I see.

He was the best. We run off to Mexico together. When we were kids. When our folks died. We went down there to see about gettin back some horses they’d stole. We was just kids. He was awful good with horses. […] I’d give about anything to see him one more time.

[…]

She patted his head. Gnarled, ropescarred, speckled from the sun and the years of it. The ropy veins that bound them to his heart. There was map enough for me to read. There God’s plenty of signs and wonders to make a landscape. To make a world. She rose to go.

Betty, he said.

Yes.

I’m not what you think I am. I aint nothin. I don’t know why you put up with me.

Well, Mr. Parham, I know who you are. And I do know why. You go to sleep now. I’ll see you in the morning.

Yes mam.

That moves me so much, perhaps, because, as young as I still am in years lived, I feel so much like that, of no great account and in the end unworthy of any particular remembrance. As if all I’d dreamed in my youth had come to nought, as if, as in these tragic lives, things had really turned out much differently from what was dreamed. As, in essence, they have, and of course must. Even if, as I still dream in unguarded moments, I’ll be like Frank McCourt, retired schoolteacher whose first book becomes a sensation. Even so, the lived experience of this world can be nothing like what I had once hoped. My marriage, for all its stubborn persistence, is far away from the youthful idyll that lent it such promise, and my loss of faith in any orthodox religion has marred the happiness that we had mapped out for each other. And so much else has happened. It really is as the character in Cities of the Plain said. What’s the hardest lesson to be learned? “I don’t know. Maybe it’s just that when things are gone they’re gone. They aint comin back.”

Picasso’s Guernica was inspired by the bombing by General Franco’s forces, during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), of the town by that name in Spain’s northern Basque region.

The title of that last novel, Cities of the Plain, is suggested in a brief passage in The Crossing, in which a lone Mormon heretic comments on the justice of God in context of a Mexican earthquake. It is Biblical in origin, no doubt, referring subtly (never directly) to the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah for their sins against humanity, their sexual perversions and terrible violence. This is a fair allusion given the inhumanity of the sex trade taking place in this Mexican city, fed by the lust of its twin American city and the violence done to the simplest of the residents on either side of the border.

One significant idea running through this trilogy, expressed most explicitly as the boy Billy Parham is trying to recover his stolen and brutalized wolf, is the arbitrariness of national borders and the price that is paid by the poor and powerless denizens that are caught up in their national or international politics. He speaks of this matter with one of the wolf’s captors, who are using it as bait in a public dog fight, from which agony the boy will ultimately have no choice but to release it by shooting it.

You think this country is some country you can come here and do what you like.

I never thought that. I never thought about this country one way or the other.

Yes, said the hacendado.

We was just passin through, the boy said. We wasn’t botherin nobody. Queríamos pasar, no más.

Pasar o trespasar?

The boy turned and spit into the dirt. He said that the tracks of the wolf had led out of Mexico. He said the wolf knew nothing of boundaries. The young don nodded as if in agreement but what he said was that whatever the wolf did or did not know was irrelevant, and that if the wolf crossed that boundary it was perhaps so much the worse for the wolf but the boundary stood without regard.

[…] The boy only said that if he were allowed to go he would return with the wolf to America and that he would pay whatever fine he had incurred but the hacendado shook his head. He said that it was too late for that and that anyway the alguacil had taken the wolf nto custody and it was forfeit in lieu of the portage. When the boy said that he had not known that he would be required to pay in order to pass through the country the hacendado said that then he was in much the same situation as the wolf. (italics mine)

This passage reveals a quality of the text that I greatly enjoyed, the bilinguality of it. Indeed, whenever direct quotes involve spoken Spanish, the words are recorded as spoken in Spanish. In this case, the Mexican party does use some English. In other cases, where this is not so, a significant exchange may take place entirely in Spanish, but it is quickly followed with narrative in English and with the use of indirect quoting so that the non-Spanish-proficient reader will still not be lost. This is a technique that I find, together with the dispensing with orthodoxies of punctuation, makes the story more authentic and immediate than it would otherwise feel. In fact, it is through this authenticity that much of the novel’s central beauty is revealed, as in this exquisite and tender passage in All the Pretty Horses:

After awhile the two girls came back. The taller of them held up her hand with two cigarettes in it.

John Grady looked at the guards. They motioned the girls over and looked at the cigarettes and nodded and the girls approached the bench and handed the cigarettes to the prisoners together with several wooden matches.

Muy amable, said John Grady. Muchas gracias.

They lit the cigarettes off one match and John Grady put the other matches in his pocket and looked at the girls. They smiled shyly.

Son americanos ustedes?

Sí.

Son ladrones?

Sí. Ladrones muy famosos. Bandoleros.

They sucked in their breath. Qué precioso, they said. But the guards called to them and waved them away.

Dust Bowl migrant with children

That simple passage, the boy lying heroically to please the child, the child sucking in her breath and saying, “How precious,” moved me more deeply when I first read it than I can say. I hope the more sophisticated English-language reader, picking up at least on “famosos” and “bandoleros” and “precioso” would catch some of the reason for that. In any case, what is implicit here is explicit in other places, as in The Crossing where Boyd’s other life as a Mexican bandolero, an American Robin Hood casting his lot among his poorer brethren, is immortalized in popular balladry. The poor and powerless pitted against the rich (albeit only comparatively) and powerful countrymen who represent law and order: to them the famous bandoleros are naturally enough precious, worthy of their love and honor. So it is fitting, as John Grady and his friend are led off then, that those little girls were seen crying.

There are many other passages, in either of these novels, of supreme beauty and truthfulness. One of my favorites, if not my absolute favorite, is from All the Pretty Horses, when John Grady and his friend are working at the ranch. They go off into the mountains with a bunch of horses and the Mexican vaqueros and an old survivor of the Mexican Revolution named Luis. Luis speaks some truths about men and horses and the souls of both of them:

… He’d loved horses all his life and he and his father and two brothers had fought in the cavalry but they’d all despised Victoriano Huerta above all other visited evils. He said that compared to Huerta Judas was himself but another Christ and one of the young vaqueros looked away and another blessed himself. He said that war had destroyed the country and that men believe the cure for war is war as the curandero prescribes the serpent’s flesh for its bite. He spoke of his campaigns in the deserts of Mexico and he told them of horses killed under him and he said that the souls of horses mirror the souls of men more closely than men suppose and that horses also love war. Men say they only learn this but he said that no creature can learn that which his heart has no shape to hold. His own father said that no man who has not gone to war on horseback can ever truly understand the horse and he said that he supposed he wished that this were not so but that it was so.

Lastly he said that he had seen the souls of horses and that it was a terrible thing to see. He said that it could be seen under certain circumstances attending the death of a horse because the horse shares a common soul and its separate life only forms it out of all horses and makes it mortal. He said that if a person understood the soul of the horse then he would understand all horses that ever were.

[…]

Y de los hombres? said John Grady.

The old man shaped his mouth to answer. Finally he said that among men there was no such communion as among horses and the notion that men could be understood at all was probably an illusion. Rawlins asked him in his bad Spanish if there was a heaven for horses but he shook his head and said that a horse had no need of heaven. Finally John Grady asked him if it were not true that should all horses also perish from the face of the earth the soul of the horse would not also perish for there would be nothin out of which to replenish it but the old man only said that it was pointless to speak of there being no horses in the world for God would not permit such a thing.

As to why this passage moves me so deeply, I, who would not even know how to ride a horse, I can only say that it takes my breath away. So does this whole trilogy, which I place in my heart’s canon alongside the Quixote and the best of the Russian masters. Even as it breaks my heart, it has the power that only great literature can of repairing it. At least in that moment that I can hold it there, before sinking again into the banal struggles of my prosaic existence.

As to why this passage moves me so deeply, I, who would not even know how to ride a horse, I can only say that it takes my breath away. So does this whole trilogy, which I place in my heart’s canon alongside the Quixote and the best of the Russian masters. Even as it breaks my heart, it has the power that only great literature can of repairing it. At least in that moment that I can hold it there, before sinking again into the banal struggles of my prosaic existence.

Advertisements Share this:

![Okey Ndibe [Photo: The Paradigm]](/ai/032/360/32360.jpg)