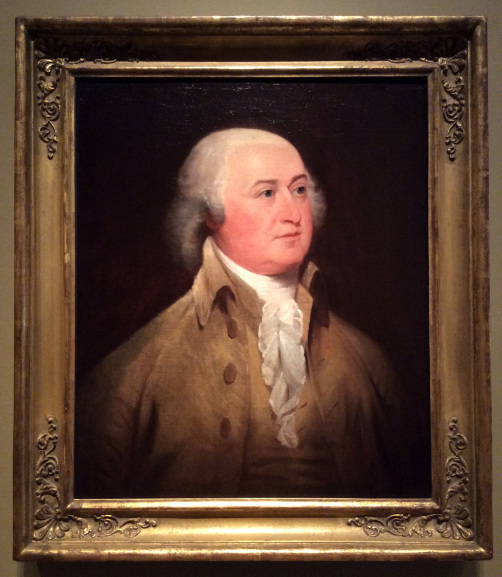

Photo by Howard Hsu, from his 2014 rust belt collection. Subject: “Kristen Hunninen, Senior Apprentice at Braddock Farms, an urban farm in the shadow of a working steel mill in Braddock, Pennsylvania.”

Photo by Howard Hsu, from his 2014 rust belt collection. Subject: “Kristen Hunninen, Senior Apprentice at Braddock Farms, an urban farm in the shadow of a working steel mill in Braddock, Pennsylvania.”

Essay continued from Part 2:

Salvage. To reclaim, recoup. In an often very subtle way, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Michigan author of 2009 story collection American Salvage (finalist for the National Book Award) saves her characters—and us in the reading. Her characters and the predicaments in which they find themselves are not pretty; yet, Campbell provides a modicum of redemption—the American Dream renewed—I’m looking for in the writing of the Rust Belt.

Campbell’s stories center on everyday people with everyday struggles—from farmers to salvage yard workers, meth addicts to the unemployed—striving to make do with the hand they’ve been dealt in the tough Michigan landscape. These stories are what Ruin Porn could do more of: show us the despairing scene and then populate it with characters to care about.

One of Campbell’s young characters, a 14-year old girl (whose story Campbell expands on for her gem of a novel, Once Upon a River), encapsulates the heart of Campbell’s fiction. In “Family Reunion,” the reader understands that the girl will take revenge by shooting the uncle who violated her. One sentence speaks volumes:

She had to do this thing for herself; nobody is going to do it for her.

Okay, retribution is not the same as redemption, but the reader understands that the two are kin, anyway, for this young girl. If there’s another line that could better hearken back to the Horatio Alger stories of industry and pulling yourself up by the bootstraps (even if it means the girl will put a bullet in her uncle), I don’t know what it might be.

The girl doesn’t exactly resurrect; she salvages. All is not saved, but all is not lost—not for Campbell’s sympathetic girl-with-a-gun. And all is not lost for us writers, readers, and doers in the Rust Belt and beyond.

Maybe the American Dream isn’t entirely lost. But neither is the heyday of industry repeatable. It’s time for a revised dream. A re-envisioning, maybe from a female angle. Is this where I say the future is female? The next American Dream—what shall we call it?—will be conceived and written and built by women? I don’t know. That way we’d lose half the dreamers.

The more I read and write about the place I’m from, the more I hope it’s a collective salvaging by families, villages, and towns with their beautiful architecture—and more importantly, people—to save. And the more I hope what I write and read reflects not a void, but a place worth salvaging.

Which brings me back to the haunting images of Ruin Porn that leave me cold. Why? Because these places aren’t truly haunted. Even if there are no people in the photographs, themselves, there are people on the periphery. The images—remnants of a gilded age lost—are beautiful, many of them. And yet I can’t call the photos beautiful because there are no bearers of beauty to be found in them. (Which is why I was so taken with Howard Hsu’s photos of the Rust Belt, like the one above.)

In Queen of the Fall: A Memoir of Girls and Goddesses, Sonja Livingston calls women “the bearers of beauty.” Indeed, beautiful female American lives unfold all around the author in this memoir, as Livingston’s own life unfolds—all over the U.S., including in western New York. In her essay, “A Party, in May,” a freak snowstorm, almost biblical in its bad timing, rains down on a celebration, a birthday party, which happens to coincide with the last night of the author’s pregnancy. There will be no birth for this unborn child, but beauty does pierce the sadness. The last line, from the morning after the storm:

Except for a few fallen blossoms, no one would have known how cold it had been just a few hours before, the snow falling and melting while most people slept.

Women are the bearers of beauty, in a literal way—as in procreation, but also as in creation of the artistic and built variety. But some of Livingston’s girls and goddesses travel through tough terrain, even ruin—of poverty plain and poverty in relationships—and even the little wins are hard-won.

Beauty does push its way through the cracks, however. Like in this moment, in Livingston’s piece, “Mock Orange.” The author is describing an almost indescribable quality—a luminescence—of her sixteen-year-old niece, who has just discovered that she is pregnant:

If you passed her in your car—maybe she’s laughing with a group of friends, maybe she’s waiting for a bus on Lake Avenue, or sitting alone on a porch with broken front steps—would you see the light coming from her or would she be to you just another pregnant girl in the city, belly looming like the moon over her tiny feet?

I can see those broken front steps made beautiful by this girl’s relation to them. Such a life is no dream, but it’s beautiful all the same.

Don’t you think? Comment and let me know.

As for the 212-page prize—in an earlier post I mentioned the spring 2017 issue of Sou’wester, in which my short story, “Betting Blind,” appeared. I’d love to gain more followers interested in Rust Belt reading and writing. So, spread the word to your social media contacts about Rust Belt Girl; get me two followers; and when they’ve tagged along with us for two weeks, I’ll put a copy of the Sou’wester issue in the mail to your continental U.S. address.

~ All Best, Rebecca

Advertisements Share this today: