This is third blog in a series, to read first 2 blogs, kindly visit here:

1st: https://muhammadsalmanisrar.wordpress.com/2017/10/14/power-of-habit-notes-part-1/

2nd: https://muhammadsalmanisrar.wordpress.com/2017/10/14/power-of-habit-notes-part-2/

STEP THREE: ISOLATE THE CUE

About a decade ago, a psychologist at the University of Western Ontario tried to answer a question that had bewildered social scientists for years: Why do some eyewitnesses of crimes misremember what they see, while other recall events accurately?

The recollections of eyewitnesses, of course, are incredibly important. And yet studies indicate that eyewitnesses often misremember what they observe.

They insist that the thief was a man, for instance, when she was wearing a skirt; or that the crime occurred at dusk, even though police reports say it happened at 2:00 in the afternoon. Other eyewitnesses, on the other hand, can remember the crimes they’ve seen with near-perfect recall.

Dozens of studies have examined this phenomena, trying to determine why some people are better eyewitnesses than others. Researchers theorized that some people simply have better memories, or that a crime that occurs in a familiar place is easier to recall. But those theories didn’t test out—people with strong and weak memories, or more and less familiarity with the scene of a crime, were equally liable to misremember what took place.

The psychologist at the University of Western Ontario took a different approach. She wondered if researchers were making a mistake by focusing on what questioners and witnesses had said, rather than how they were saying it. She suspected there were subtle cues that were influencing the questioning process. But when she watched videotape after videotape of witness interviews, looking for these cues, she couldn’t see anything. There was so much activity in each interview—all the facial expressions, the different ways the questions were posed, the fluctuating emotions—that she couldn’t detect any patterns.

So she came up with an idea: She made a list of a few elements she would focus on—the questioners’ tone, the facial expressions of the witness, and how close the witness and the questioner were sitting to each other. Then she removed any information that would distract her from those elements. She turned down the volume on the television so instead of hearing words, all she could detect was the tone of the questioner’s voice. She taped a sheet of paper over the questioner’s face, so all she could see was the witnesses’ expressions. She held a tape measure to the screen to measure their distance from each other.

And once she started studying these specific elements, patterns leapt out. She saw that witnesses who misremembered facts usually were questioned by cops who used a gentle, friendly tone. When witnesses smiled more, or sat closer to the person asking the questions, they were more likely to misremember.

In other words, when environmental cues said “we are friends”—a gentle tone, a smiling face—the witnesses were more likely to misremember what had occurred. Perhaps it was because, subconsciously, those friendship cues triggered a habit to please the questioner.

But the importance of this experiment is that those same tapes had been watched by dozens of other researchers. Lots of smart people had seen the same patterns, but no one had recognized them before. Because there was too much information in each tape to see a subtle cue.

Once the psychologist decided to focus on only three categories of behavior, however, and eliminate the extraneous information, the patterns leapt out.

Our lives are the same way. The reason why it is so hard to identify the cues that trigger our habits is because there is too much information bombarding us as our behaviors unfold. Ask yourself, do you eat breakfast at a certain time each day because you are hungry? Or because the clock says 7:30? Or because your kids have started eating? Or because you’re dressed, and that’s when the breakfast habit kicks in?

When you automatically turn your car left while driving to work, what triggers that behavior? A street sign? A particular tree? The knowledge that this is, in fact, the correct route? All of them together? When you’re driving your kid to school and you find that you’ve absentmindedly started taking the route to work—rather than to the school—what caused the mistake? What was the cue that caused the “drive to work” habit to kick in, rather than the “drive to school” pattern?

To identify a cue amid the noise, we can use the same system as the psychologist: Identify categories of behaviors ahead of time to scrutinize in order to see patterns. Luckily, science offers some help in this regard. Experiments have shown that almost all habitual cues fit into one of five categories:

Location

Time

Emotional state

Other people

Immediately preceding action

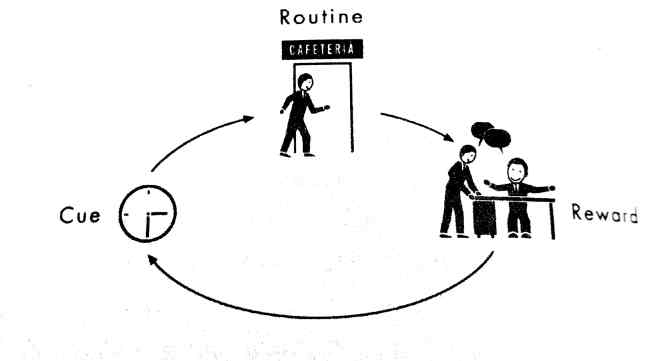

So if you’re trying to figure out the cue for the “going to the cafeteria and buying a chocolate chip cookie” habit, you write down five things the moment the urge hits (these are my actual notes from when I was trying to diagnose my habit):

Where are you? (sitting at my desk)

What time is it? (3:36 P.M.)

What’s your emotional state? (bored)

Who else is around? (no one)

What action preceded the urge? (answered an email)

The next day:

Where are you? (walking back from the copier)

What time is it? (3:18 P.M.)

What’s your emotional state? (happy)

Who else is around? (Jim from Sports)

What action preceded the urge? (made a photocopy)

The third day:

Where are you? (conference room)

What time is it? (3:41 P.M.)

What’s your emotional state? (tired, excited about the project I’m working on)

Who else is around? (editors who are coming to this meeting)

What action preceded the urge? (I sat down because the meeting is about to start)

Three days in, it was pretty clear which cue was triggering my cookie habit—I felt an urge to get a snack at a certain time of day. I had already figured out,

in step two, that it wasn’t hunger driving my behavior. The reward I was seeking was a temporary distraction—the kind that comes from gossiping with a

friend. And the habit, I now knew, was triggered between 3:00 and 4:00.

To read the last blog in the series, kindly visit: https://muhammadsalmanisrar.wordpress.com/2017/10/14/power-of-habit-notes-part-4/

Image credits:

-Feature image: https://www.amazon.com/Power-Habit-What-Life-Business/dp/081298160X

-Images used in the blog were scanned directly from paperback.

Advertisements Share this: