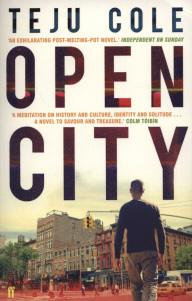

I’ve been an avid reader of Teju Cole’s prose since 2011, when I first read his debut novel, Open City.

Reading the novel had left an immense impression on me, but I was reluctant at the time to read his only other book, Every Day is for the Thief, perhaps because it was officially labeled as trailing in there, somewhere between fiction and non-fiction (I have since changed my reading habits. In fact I seem to read more non-fiction than fiction these days.)

The years have gone by, though, and there was no sign that Mr. Cole is due to release any new title. Finally, curiosity got the best of me, and I purchased Every Day is for the Thief and almost immediately devoured it. Bleak though it is, and obviously not in the same stature as Open City, Every Day is for the Thief nevertheless is an impressive travelogue or an analysis of the unnamed American-Nigerian narrator’s psyche.

Cole’s writing left a craving for more. A craving that was thankfully satisfied this year, with the publication of two new books: a collection of essays named Known and Stranger Things and a Pictures-Texts book aptly named Blind Spot, both of which were purchased, needless to say, immediately after their release.

***

How much do we remember of a novel once we’ve gone through reading it? What is left of it hours after we’re done with its reading? What remains after days, months, years? Are we only left with the general impression, a blurry map of its plot’s outlines? Or is it the little anecdotes, the insignificant details that we remember most?

There is so much white noise constantly ringing around us, so many endless sounds competing over our attention.

Revisiting Teju Cole’s Open City was an occasion I’d been unconsciously preparing myself to for a good few years. I rarely re-read books. There are too many unread books in my library, too many unpurchased titles in my Amazon Wish List. Not enough time to read them all, helás.

The wait was worthwhile. The book has much improved over the years. The passing time has lent it wisdom and foresight which could not have been easily detected back in 2011.

What was it that originally appealed to me in Mr. Cole’s book? Why did I (like so many others) relate so much to its overall bleak depiction of today’s world? What made me sympathize with the book’s narrator, drenched in melancholy as he was?

In the first reading, I read Open City as a philosophical novel, a modern novel of ideas, a relentless analysis of our times.

My second reading, inevitably, was doomed to be more critical, less open-minded, if you will. I still found the plot ingeniously woven by the hands of a sage (it’s quite amazing to realize that when the novel was published, Mr. Cole was only 35, and he’d been struggling with its writing since the age of 29.)

Reading Open City for the second time, I noticed many details I had forgotten over the years. I paid close attention to the many digressions in the plot . I detected a couple of recurring themes (blindness is key amongst them.) And I was quite surprised to discover that I had totally forgotten both the novel’s beginning and ending (the latter was especially surprising.)

Published in early 2011, the novel was read at the time as a ‘classic’ post-9/11 novel. The signs were all there. The novel’s narrator and main protagonist, Julius, aimlessly wanders the streets of Manhattan, anticipating devastation and doom for humankind.

‘The sight of large masses of people hurrying down into the underground chambers was perpetually strange to me, and I felt that all of the human race were rushing, pushed by a counterinstinctive death drive, into movable catacombs. Aboveground I was with thousands of others in the solitude, but in the subway, standing close to strangers, jostling them and being jostled by them for space and breathing room, all of us reenacting unacknowledged traumas, the solitude intensified’

His profession as psychiatrist lends him no consolation either (in one atypical conversation with three other friends, practically the only real social interaction which takes place in the entire novel, Julius confides to his interlocutors that some of his patients are real ‘nut jobs‘.)

The Manhattan Cole depicts is an island of ghosts. Ghosts of the distant past, certainly, but also ghosts of the present. There is hardly any communication taking place amongst the many human beings populating this dense island. They walk the streets, strangers to each other, their identity unrevealed, their destinations unknown. Julius is just one amongst them, a ghost amongst ghosts.

Rereading Open City, there is no doubt in my mind that Julius is suffering from acute depression. At two points in the novel he experiences what could only be described as an identity crisis, a near-total-meltdown of the self, of his identity as a human being.

The first time, it occurs after he continuously forgets his four-digit code for his bank card and fails to withdraw money from a cash machine. This leads to a moment of confusion, followed by a quick rationalization:

‘… my mind was empty, subject to a nervous condition: this was the expression that came to me as I stood there, as though I had become a minor character in a Jane Austen novel. Such sudden mental weakness, I thought (as the machine asked if I would like to try again, and I did and failed again),was from a simplified version of the self, an area of simplicity where things had once been more robust. This was true of a broken leg, too: one was suddenly lessened, walking with an incomplete understanding of what walking was about.’

The second time, it occurs when Julius is visiting an obscure little shop in downtown Manhattan. Entering the shop, he feels as though he’d been sucked out of present-reality, an overwhelming emotion that’s finally disturbed by the unusual sounds of a brass band, marching in the street outside the shop:

‘Whether it expressed some civic pride or solemnized a funeral I could not tell, but so closely did the melody match my memory of those boyhood morning assemblies that I experienced the sudden disorientation and bliss of one who, in a stately old house and at a great distance from its mirrored wall, could clearly see the world doubled in on itself. I could no longer tell where the tangible universe ended and the reflected one began. This point-for-point imitation, of each porcelain vase, of each dull spot of shine on each stained teak chair, extended as far as where my reversed self had, as I had, halted itself in midturn. And this double of mine had, at that precise moment, begun to tussle with the same problem as its equally confused original. To be alive, it seemed to me, as I stood there in all kinds of sorrow, was to be both original and reflection, and to be dead was to be split off, to be reflection alone.’

And a few pages later he bleakly notes:

‘sometimes it is hard to shake the feeling that, all jokes aside, there really is an epidemic of sorrow sweeping our world, the full brunt of which is being borne, for now, by only a luckless few’

I’ve mainly focused on my reading of Julius’ character in this post. Yet rereading Open City I’ve realized that there are so many other aspects in this novel which require a more detailed analysis (which is partially the reason I’ve started writing this blog..)

One final comment.

When I originally read Open City, some 6 years ago, I read the first UK paperback edition. The large yellow letters sprawled across the novel’s dark cover in all likelihood referred to ‘Time Square’s neon inferno’ Cole alludes to in the novel’s final pages. The second UK paperback edition, which I happened to reread the novel on, features a shot of a dark skin man taken from behind. The man’s posture shows purpose and intent. He is well built and his clothes also suggest an army outfit. He looks like someone with a vengeance. He’s out to get someone. In short, he is the total contrast of the frail image one imagines for Julius, the Nigerian-American psychiatrist who spends his lonely evenings listening to Purcell or Mahler.

Advertisements Share this: