Stella Schools Ambassador, Sarah Ayoub, chats with Blogger in Residence, Nalini Haynes, about writing, diversity and representation.

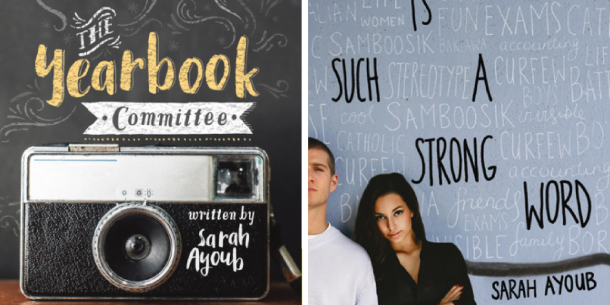

Can you tell us a little bit about your novel The Yearbook Committee?

In an inner-western Sydney private school, five students work on the school’s yearbook; most come from wealthy families except one scholarship student. It kicks off at the end of their HSC, at a party where an ambulance takes someone away, then the story goes to the beginning of the school year.

And your debut novel, Hate Is Such A Strong Word?

It was inspired by my upbringing in southwestern Sydney in a traditional Christian Lebanese family. My parents migrated from Lebanon, but I was born in Australia. I went to a monocultural school from kindergarten to year 12. By year 10, I felt I was living in a bubble.

Adolescence is hard enough with questions about your future, interactions with both the opposite sex and the same sex, changing friendships…

For me this was harder, because in the late nineties and early naughties, Lebanese people were the scum of Australian crime. The police commissioner and the NSW premier talked about the community as if we were all criminals. I thought if we interacted more with society, people could see beyond our stereotypes. When I went to university I felt I was challenging those stereotypes all the time.

Are there a lot of Christian Lebanese?

Definitely, we are a significant sub-culture. I wanted Sophie to retain that identity because people assume I’m Muslim just because I was from the Middle East. Not that I was offended, but I want to give my people a voice.

Some reviewers believe that Hate Is Such A Strong Word is one of too many books about people from non-English speaking backgrounds.

There is a bigger push for diverse stories now and diversity can come in all sorts of different stories. There can never be enough. A lot of people from very different backgrounds and very different opinions live in Australia. The more diverse stories we have, the more they reflect our population.

Books offer empathy and understanding. Sometimes a story written by a nonwhite person or a person from a different religion or sexuality helps you understand what they’re going through.

Diversity is gender, culture, religion, everything. There can never be enough because our society is always changing. Even two Lebanese girls stories are very different. We need to speak to young people in the language they know, with characters they understand or with characters they have never met, to develop our society into a more cohesive, more understanding community.

Can you tell us a little bit about how you tackle diverse issues—more specifically in regards to your second novel The Year Book Committee?

The really posh private schools have a few students from non-English speaking backgrounds, but the majority are white. I wrote a posh private school that was authentic.

Diversity doesn’t just mean cultural and linguistically diverse characters. My characters come from blended or single-parent families; one has a mother with mental illness, another has a brother with Down’s Syndrome. The scholarship student comes from a housing commission area, lower socio-economic status. That is diversity.

There are five main characters in The Yearbook Committee and one of them is half Greek, so her Yiayia is briefly mentioned. Some minor characters are diverse: Muhammad is a Palestinian Muslim and there’s also an Italian. Who the characters are is relative to their role in the playground, their role in the committee and each other’s lives. The story isn’t an ethnic struggle, but I am normalising people of colour and people who are culturally diverse by putting them in.

As a writer I should be treated like any other creative. Just because I come from a non-English speaking background doesn’t mean I have to write only about culturally and linguistically diverse characters.

If you write white characters, you face criticism for not getting the diversity right. But if you write non-white characters and get something wrong or someone takes offence, you face criticism for cultural appropriation or misrepresenting a community. It can be very hard. Unless I know an ethnic group well, they are not going to be a major character in one of my stories. I know what it feels like when people assume things or get things wrong.

I don’t want to get anything wrong. For example, I don’t know what it’s like to come out of the closet, so I don’t know if I could write a main character struggling with that. I could write a secondary character who is ‘out’ because the struggle, the revelation, isn’t there.

Whereas I know what it feels like when your parents are fashioning a future for you that you don’t want, if your friend stops talking to you or if someone gets bullied and you don’t know what to do. That stuff I can write about.

But to write about an Aboriginal girl growing up Australian—who she really is—I don’t know what that’s like. When I talk about diversity I mean ‘let’s publish authors of diverse backgrounds’. Allow them to tell their stories. They should have their voice. We should promote their voices.

“When I was 4 years old, I discovered a large hardcover book of poetry in a corner store and my father bought it for me. Later he wanted me to read ‘Triantiwontigongolope’ by CJ Dennis. I said the poem was silly; I couldn’t possibly read a word THAT BIG so the trees and grass being purple was a great excuse. My father challenged me to think about possibilities in this strange world. I knew my disability separated me from others so I asked ‘Could I be normal in a world like that?’ He said ‘Yes’. Thus my love of genre and my passion for social justice were sown with the hope of changing the world.”

“When I was 4 years old, I discovered a large hardcover book of poetry in a corner store and my father bought it for me. Later he wanted me to read ‘Triantiwontigongolope’ by CJ Dennis. I said the poem was silly; I couldn’t possibly read a word THAT BIG so the trees and grass being purple was a great excuse. My father challenged me to think about possibilities in this strange world. I knew my disability separated me from others so I asked ‘Could I be normal in a world like that?’ He said ‘Yes’. Thus my love of genre and my passion for social justice were sown with the hope of changing the world.”

— Nalini Haynes.

You can find Nalini at: her website, Dark Matter Zine,Twitter as Dark Matter Zine and as herself, Facebook as Dark Matter Zine and as herself, Instagram,Pinterest and Tumblr.