This is Sarah’s final installment on WWII Army Hospitals. I’d like to thank Sarah for all her hard work on these terrific posts. Click the links for Part I and Part II.

US Army Hospitals in World War II—Part 3

Ruth squatted beside his cot. “Have you ever flown before, Corporal?”

“No, ma’am. A man’s meant to stay on the ground.”

“How long did it take you to get to England?”

“Almost two months, ma’am, zigzagging around them U-boats.”

“Mm-hmm. Well, tonight you’ll have dinner in New York. You may change your mind about flying.”

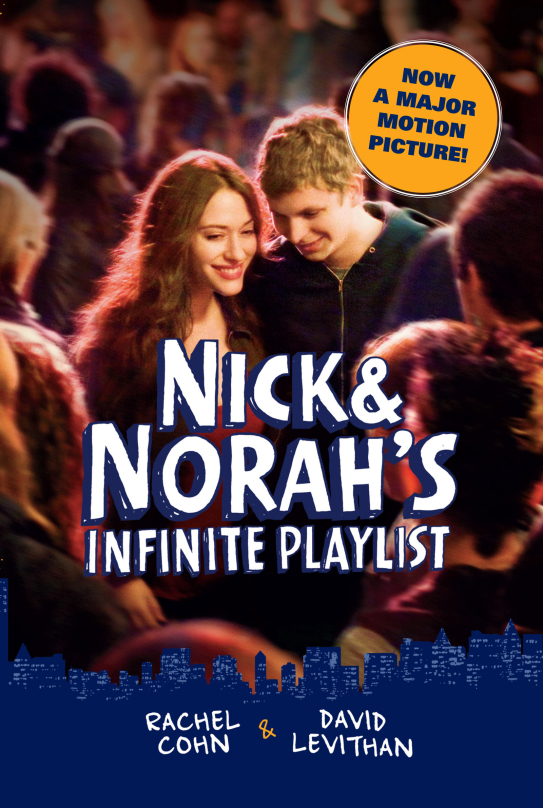

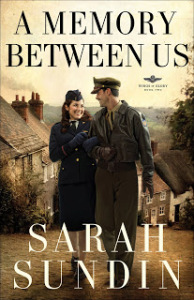

In my novel A Memory Between Us, the heroine becomes a flight nurse, pioneering medical air evacuation. If you’re writing a novel set during World War II, a soldier character may get sick or wounded, and you’ll need to understand how patients were evacuated from the battleground to the hospital and perhaps taken stateside.

In my novel A Memory Between Us, the heroine becomes a flight nurse, pioneering medical air evacuation. If you’re writing a novel set during World War II, a soldier character may get sick or wounded, and you’ll need to understand how patients were evacuated from the battleground to the hospital and perhaps taken stateside.

In my first post, I discussed the chain of evacuation. In my second post, I discussed more details about mobile and fixed hospitals, and today I’ll cover evacuation of the wounded.

Manual Transport

On the battleground, medics or fellow soldiers could manually carry a wounded man further to the rear for aid. Methods included the supporting carry (walking side-by-side), the arms carry, the saddleback carry (piggy-back), and the fireman’s carry.

Litter Transport

American litters were made of canvas stretched over aluminum or wood poles with stirrup-shaped feet to keep them off the ground. A litter could be carried by two people, but a litter squad consisted of four men, to rotate if traveling long distances and to assist over obstacles. Ideally, litter transport was only used for short distances, but in mountainous or forested or swampy terrain, litter transport was the only available means. Mules were often used in the Mediterranean Theater to carry litters in rocky, mountainous terrain.

Motor Transport

Ambulances were used to transport patients, usually from an aid, clearing, or collecting station to a field hospital, or for transport further to the rear. Ambulances could carry seven seated patients or four patients on litters.

Water Transport

Jeeps were often used, both on the battleground and to transport further to the rear. Rugged and maneuverable, jeeps could cover terrain inhospitable to ambulances. With litter brackets, a jeep could carry two patients. Armored divisions also used light tanks to transport their wounded.

During an amphibious landing, the best way to handle the wounded was to send them back on departing landing craft, which carried them to hospital ships off-shore. Patients could be removed from danger and transported quickly to get needed care.

Hospital ships were used offshore after an invasion to care for the wounded before field and evacuation hospitals could be set up. They also transported patients who needed long-term care to general hospitals further to the rear. Another use of hospital ships was to transport to the US any patients who needed long-term convalescent care or those who qualified for a medical discharge. They carried several hundred patients and delivered full medical care, but transport took a long time and carried the danger of enemy attack at sea.

Rail Transport

Hospital trains were used within theaters of operation to transport patients from one hospital to another. They were used in the continental US, Britain, continental Europe, India, and North Africa. They could carry several hundred patients with excellent medical care.

Air Transport

Medical air evacuation was new and revolutionary, but by the end of the war, it proved successful. Planes can traverse inhospitable terrain or dangerous seas—and quickly. At the front, the wounded were gathered at collecting stations at airfields. C-47 cargo planes carried 18-24 litter patients or a higher number of ambulatory patients further to the rear. A team consisting of a flight nurse and a surgical technician cared for the patients in flight. The larger C-54 cargo plane was used for trans-oceanic evacuation. Danger still existed, both from the inherent risks of flight and also because the planes carried cargo and couldn’t be marked with the Red Cross.

Resources for Research

Office of the Surgeon General. Medical Field Manual: Transportation of the Sick and Wounded. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, Feb. 21, 1941 (available free on-line at http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/ref/FM/index.html ). Please note the date—some of the material, especially about air evacuation, became quickly outdated.

For better information on air evacuation, please see:

Links, Mae Mills & Coleman, Hubert A. Medical Support of the Army Air Forces in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Surgeon General, USAF, 1955.

*********************************************************************************************

Sarah Sundin is the author of the Wings of Glory series from Revell: A Distant Melody (March 2010), A Memory Between Us (September 2010), and Blue Skies Tomorrow (August 2011). She has a doctorate in pharmacy from UC San Francisco and works on-call as a hospital pharmacist.

***This content is reposted from December 17th, 2010.***

Share this: