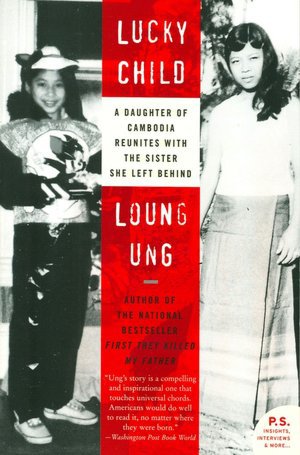

For anyone like me who had a happy childhood and a conventionally middle-American angst-ridden adolescence, it is difficult to think of anyone who was in Phnom Penh in 1975 when Angkar (known in the west as the Khmer Rouge—the Maoist Cambodian) emptied it as having been lucky. Having read Loung Ung‘s first book, First They Killed My Father I knew what she meant before beginning Lucky Child. She was a happy and privileged 5-year-old in 1975. She survived the horrors of being a suspiciously (to the Angkar cadres) light-skinned urbanite through remarkable tenacity and cunning, as the previous book details in chilling detail. There were close calls of starvation, bullets, and her family background, so some luck was involved in reaching the age of ten.

Then, there was the luck of being chosen by her eldest brother Meng to be the one to accompany him as he tried to get to the United States (through Vietnam and Thailand—yes, I know they are in opposite directions from Cambodia; read the first book to find out about this very dangerous zigzag, complete with pirates). He chose her in part because she was the youngest and most likely to adjust more easily to a(nother) new culture. She was also tougher than her surviving sister Chou.

Chou probably would have been even more lost in Vermont than Loung was, but life in America was still far from easy for Loung. Among other things, she chafed at the demands of her Elder Brother’s wife that she be demure. Having been a soldier at the age of 9 so that she could eat, demure is not how Loung survived in Cambodia. Moreover, her skin was again different from that of the majority in Essex Junction, Vermont, so that she was still suspiciously “other.” She was terrified of ghosts, carefully following Cambodian/Chinese folk remedies for warding them off. And, like many other survivors of bombings and gun-battles, frightened by Fourth-of-July fireworks.

And bearing a crushing load of survivor guilt—not just in relation to her parents and the sister who starved during the Khmer Rouge economic devolution and widespread slaughter (particularly of nonpeasants, and among them, particularly of those who looked like they have Chinese or Vietnamese ancestry), not just in relation to the million or two who died in the four years of Khmer Rouge despotism, but of her siblings who were left behind, Chou in particular.

The book alternates Loung Ung’s first-person memoirs with chapters in the third person about Chou’s experience half a world away in the village in which aunts and uncles lived. (They were “base people” to the Khmer Rouge, presumed to have supported the revolution before April 17, 1975, in contrast to those driven out of Cambodia’s cities.)

I had to wait a long ways into the book to find out what happened to Third Brother Kim, who had become the “man of the house” desperately trying to protect his mother, Loung, and Chou, and to get food for them at age nine, and who had to swallow vast quantities of bitterness and humiliation. Loung was luckier than he was in many ways, but after some more harrowing “adventures,” he, too, got to the US.

The two siblings who survived and remained in Cambodia produced five and six children, so there are many nephews and nieces in Cambodia, and the Cambodian American Ungs have been able first to help and then to visit the Cambodian ones.

As the contrast in titles already strongly suggests, Lucky Child has happier stories to tell than First They Killed My Father did. Readers of the first book can find relief in the second one and be happy for the characters. The narrative is less gripping because there are relatively mundane problems instead of nearly unimaginable horrors in the second book.

Both books have some fracturing of perspective. The first has imagined scenes—plausible conjectures about how Loung thought her family members’ ends went. The second one has the alternation between Loung and Chou. The author is more certain in telling her own story than in telling her sister’s. Loung is—and seemingly was from an early age—more introspective than Chou, and more purposeful. Chou was more passive (and a model of demureness) and is not all that interesting a character. Moreover, Loung is hard on herself and very, very gentle in writing about her sister. This is totally understandable in human terms, and I admire Loung for treating her sister well. But “kid-glove” treatment doesn’t make for as riveting reading as the self-critical narration of Loung’s own experience.

Probably it says something about the sadism and voyeurism of readers that we often find kind characters boring (and often find villains interesting and even sympathetic). I don’t think it’s just me! And I think she is too hard on herself, so am not a total sadist…

Loung Ung’s pair of memoirs, like those of Pascal Khoo Thew (From the Land of Green Ghosts) and T. C. Hou(‘s autobiographical novels A Thousand Wings and Land of Smiles) provide terrifying portraits of confused youngsters escaping brutal Southeast Asian genocidal/ethnocidal regimes in Cambodia, Burma, and Laos. They (and the accounts of leaving and returning to Vietnam in Andrew Pham’s Catfish and Mandala, Noel Alumit’s of leaving the Philippines after Marcos goons kill his father in Letters to Montgomery Clift, and leaving Afghanistan in Tamim Ansary’s West of Kabul, East of New York) make my adolescent unhappinesses seem very petty in comparison. These often poignant books may induce survivor guilt, along with telling about the lost seeming paradises of childhoods cruelly snatched away—an experience that is altogether too widespread!

©2007, 2017, Stephen O. Murray

Advertisements Share this: