The School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) recently acquired “The Personal Papers of Derek Bryan, Consular Official and Teacher” [SOAS PP MS 99]. Derek Bryan went to China in 1932, aged 21, as a student interpreter with the Foreign Office, and remained there, on and off, until 1951. Back in the UK, he worked to encourage understanding of China, writing and teaching. He was very much involved in the Britain-China Friendship Association (BCFA), and founded the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding (SACU) in 1965. Among his papers are very detailed financial accounts and letters home. Further biographical information for Hermann Derek Bryan (1910-2003) can be found on the SOAS blog.

SOAS Archivist John Langdon has kindly written this blog, focusing on Derek Bryan’s account books of the 1930s:

Derek Bryan’s career was closely tied to China, first as a consular official and later as a teacher and advocate of closer Sino-British relations. This blog post looks at what his account books, now held in SOAS Archives & Special Collections, can tell of his early days in China when he was first posted to Peking (Beijing) in the 1930s. Peking was a city on the brink of great change, and Bryan’s accounts capture a way of life that was shortly to vanish, swept away by the Japanese occupation and the Communist revolution, all witnessed by Bryan from a succession of posts in China.

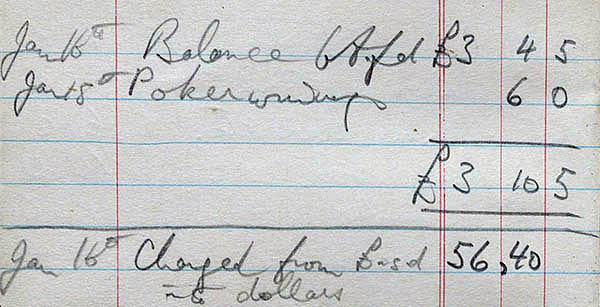

Arriving in Peking as a student interpreter in 1933, one of Bryan’s first actions was to exchange the £3 10s 5d he had left from his journey into Chinese currency. His accounts record that he received $56.40 in Chinese dollars.

Entries for January 1933, showing Bryan’s exchange of £3 10s 5d into $56.40, as well as 6s in poker winnings (PP MS 99/01/01/07) © SOAS Library

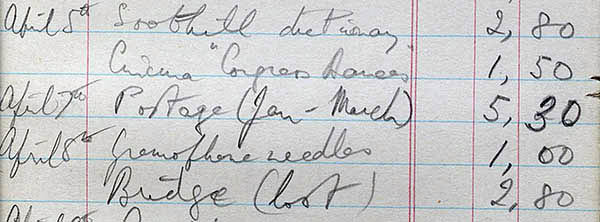

Provided with rooms in the student mess, some of Bryan’s earliest purchases show him settling into his new surroundings. The day after he arrived he bought furniture for $35.00 and was shown around Peking before spending the evening playing pin pool with one of his new colleagues. Subsequent purchases included ash trays ($0.80), a tea service ($20.20), a lampshade ($3.00) and a cocktail set ($8.80). He also had his chair covers dyed ($6.00). Bryan equipped himself with books that he needed as he learned Chinese, such as Soothill’s dictionary ($2.80).

Bryan later recalled that Foreign Office advice to students stated that there was no use for bowler hats in Peking. He may not have had a bowler, but he did make sure he had appropriate hats to hand. He bought a Panama hat for $1.20 and a straw hat for $2.30 during his first spring in Peking followed by a fur hat for $4.00 in the winter, to add to the sun helmet he had bought in Port Said on the voyage out (10s).

Once he had settled in, Bryan’s expenses became more routine. His hair cuts cost $1.00, as did regular purchases of gramophone needles. Rickshaw rides cost only a few cents. Bryan was a frequent letter writer, corresponding regularly with his family in England. His quarterly postage bills ranged from $2.00 to $10.00 in 1933. His accounts rarely mention food, except for occasional meals out, and he would presumably mostly have eaten in the student mess.

Expenses for April 1933, including Soothill’s dictionary, a cinema visit and gramophone needles (PP MS 99/01/01/07) © SOAS Library

Bryan later wrote of his student days in Peking that they ‘amounted to a small amount of Chinese culture and an endless round of Western social life’. Studying in the mornings, many of his afternoons were free to spend as he wished. His accounts record excursions, such as those to the Great Wall ($12.00 in total) and to the Summer Palace (which cost $2.80 for car hire, $1.00 for teas, and $1.50 in entrance fees) in the spring of 1933. A trip to the races in April 1933 cost Bryan $1.50 for his share of the car hire but $3.60 in betting losses. He played hockey and tennis (his hockey shirt cost $5.00, his tennis racquet and press $11.50), went riding (he gave the groom a $5.00 tip at Christmas 1933), and skated in the winter.

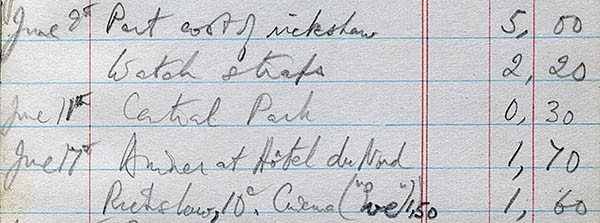

Entries for June 1933, including rickshaws and dinner at the Hôtel du Nord (PP MS 99/01/01/07) © SOAS Library

In the evenings Bryan was a frequent visitor to the cinema. His accounts list the films he saw, including Dawn Patrol, the 1930 film directed by Howard Hawks which he saw twice, or the 1932 comedy The Indiscretions of Eve directed by Cecil Lewis, which he found ‘good in parts’. Tickets were $1.50. He also played bridge and vingt-et-un, with his wins and losses set out in his accounts. Over the course of 1933 he came out behind, losing $17.05. Other evenings were spent at the club playing snooker or pin pool.

Overall Bryan lived within his budget. Bryan’s annual salary was £300, which he converted to roughly $4600. He allowed himself $40 a month for his personal expenses, not including his fixed monthly outgoings. These included his mess bill of $75, the club at $20, his bottle club at $10, and $70 for his servant. This left him able to save a significant part of his salary, particularly once he had paid the one-off costs associated with moving to a new country. It is perhaps not surprising that he later recalled he and his fellow students as having lived ‘the life of young lords’.

Advertisements Share this: