In Four Quartets, the poet T.S. Eliot wrote, “For last year’s words belong to last year’s language / And next year’s words await another voice.” Language is constantly changing and evolving. New words enter our vocabulary and our lexicon. How many of the words that we use on a daily basis would be completely strange and unfamiliar to our ancestors just a few generations ago? How many of their vernacular are lost to us now? Just as our physical landscapes are changing with development, so, too, is our language.

In Four Quartets, the poet T.S. Eliot wrote, “For last year’s words belong to last year’s language / And next year’s words await another voice.” Language is constantly changing and evolving. New words enter our vocabulary and our lexicon. How many of the words that we use on a daily basis would be completely strange and unfamiliar to our ancestors just a few generations ago? How many of their vernacular are lost to us now? Just as our physical landscapes are changing with development, so, too, is our language.

How many of us, when we venture into the woods, cannot name the trees or plants or birds or wildflowers that we come across? How many children can tell you the names of imaginary cartoon animals but not the real names of animals in nature? How many of them have been more likely to touch the latest iPhone than water in a creek or the bark of a tree as they climb it? How many of them would be more in awe of the latest video game system than in seeing a hawk in flight? When Cambridge University did a study of four to eleven year olds, what they discovered was that kids were “more inspired by synthetic subjects” than by “living creatures.” They were more excited by Pokemon than porcupines. But what are we losing when we and our children are no longer connected to the natural world? How can we care about the welfare of other creatures if we don’t even realize they exist?

As people become more and more connected to the online world, they become less and less to the natural one. As technological words enter our vocabulary and our dictionaries, the words of nature are falling away and forgotten. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language means the limits of my world.”

How limited will our world become?

When we diminish our language, we diminish ourselves.

In her book From The Forest: A Search For The Hidden Roots of Our Fairy Tales, Sara Maitland writes:

“The whole tradition of [oral] story telling is endangered by modern technology. Although telling stories is a very fundamental human attribute, to the extent that psychiatry now often treats ‘narrative loss’ — the inability to construct a story of one’s own life — as a loss of identity or ‘personhood,’ it is not natural but an art form — you have to learn to tell stories . . . The deep connect between the forests and the core stories has been lost; fairy stories and forests have been moved into different categories and, isolated, both are at risk of disappearing, misunderstood and culturally undervalued, ‘useless’ in the sense of ‘financially unprofitable.”

When I read those words, my heart broke. As someone who loves both fairy tales and forests, I fear for what we are not leaving future generations.

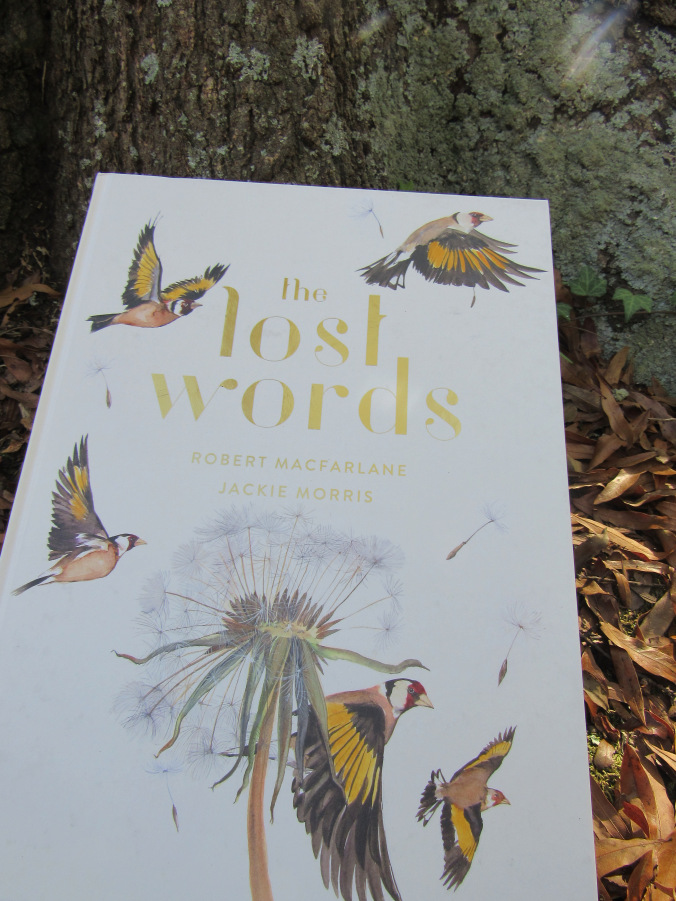

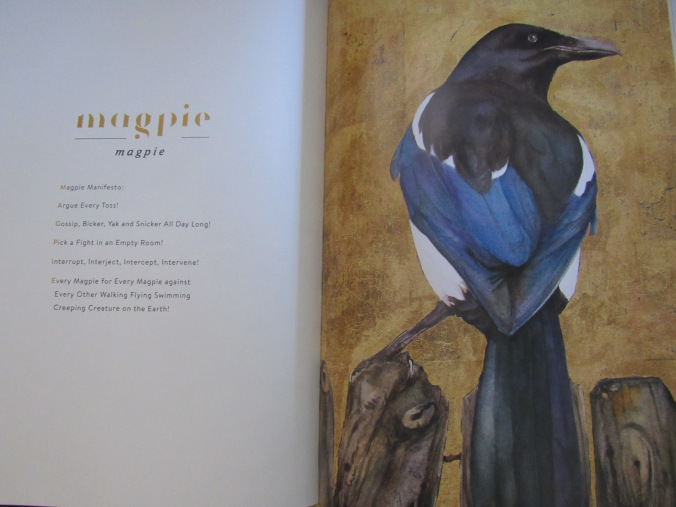

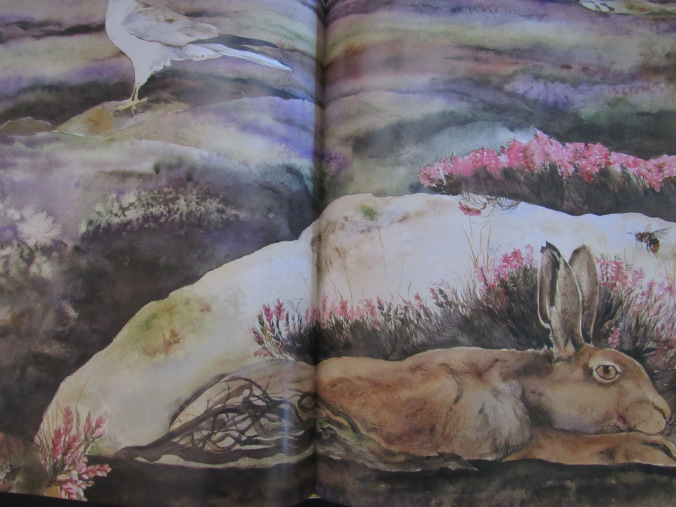

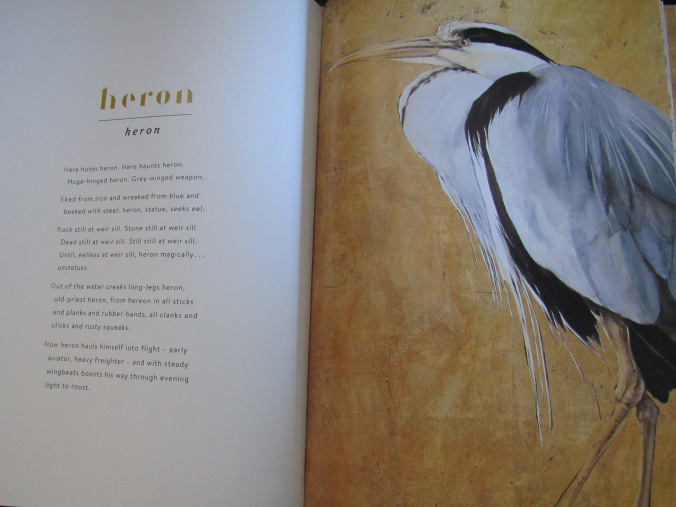

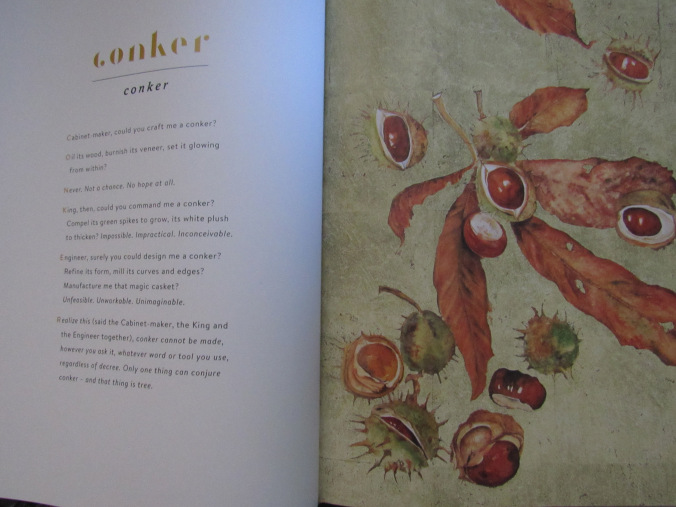

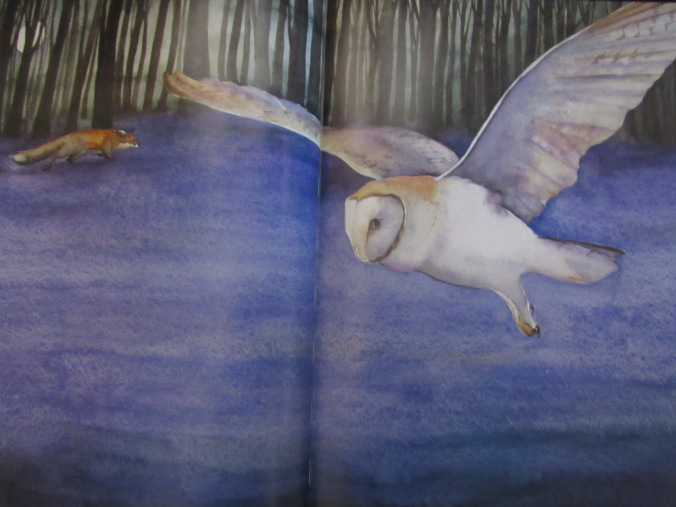

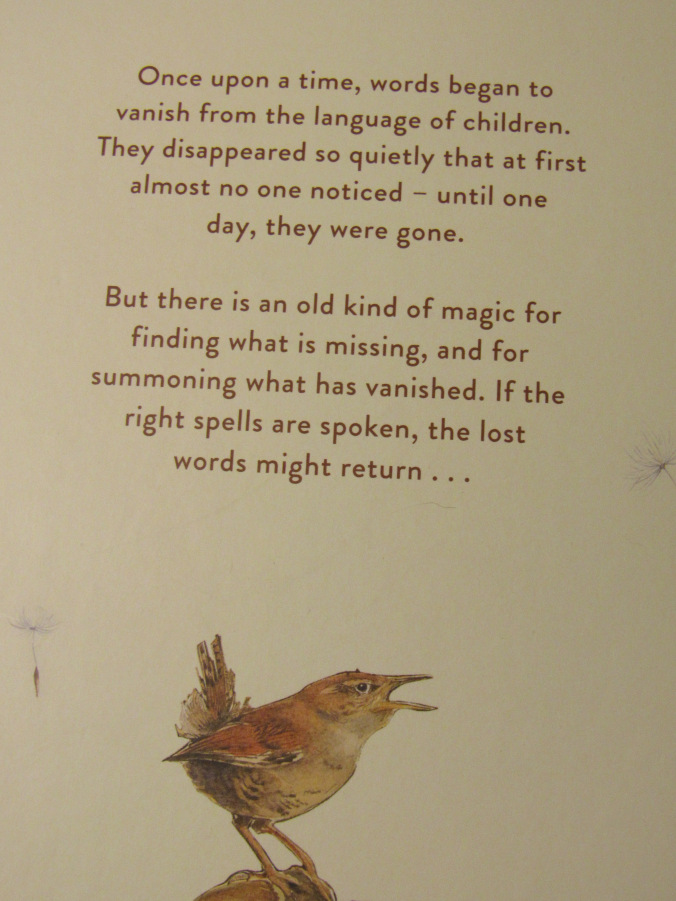

One of my favorite authors, Robert Macfarlane, has explored this loss in books like Landmarks and The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot. Now he has a gorgeous new illustrated book out entitled The Lost Words. It is astoundingly beautiful and the watercolor illustrations by Jackie Morris take my breath away in no less a fashion as seeing wildlife in nature itself. Their collaboration is a pure celebration of words, poetry and the natural world.

One of my favorite authors, Robert Macfarlane, has explored this loss in books like Landmarks and The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot. Now he has a gorgeous new illustrated book out entitled The Lost Words. It is astoundingly beautiful and the watercolor illustrations by Jackie Morris take my breath away in no less a fashion as seeing wildlife in nature itself. Their collaboration is a pure celebration of words, poetry and the natural world.

When I received The Lost Words in the mail, I could not wait to share this book with my younger son, who adores animals, the woods and, especially birds. The two of us poured over the pages of a work that compels the reader to reconnect with the outdoors again.

When I received The Lost Words in the mail, I could not wait to share this book with my younger son, who adores animals, the woods and, especially birds. The two of us poured over the pages of a work that compels the reader to reconnect with the outdoors again.

Robert Macfarlane mourned the loss of words that were disappearing from kids’ dictionaries: acorn, bluebell, heron and conker being among them. As he told The Telegraph, “The idea was that readers would feel a sense of walking into the book, like a landscape. We wanted to make a spell-book in two senses – in that children spelt these words but that there was also this great sense of enchantment; that old magic of speaking things aloud.”

As a child I discovered nature both through books (Beatrix Potter and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows were two vital ones for me) and by playing in and exploring the woods behind our house. I lament that my own sons do not have the ability to just roam free in the nature as I did, but I still make the effort to take them out on weekly nature walks and spend time in national parks where they can encounter fish in the streams, hear the piercing cry of a red-tailed hawk in flight, feel moss on their feet, see the sunlight dancing amidst the branches and leaves of the trees, and to learn the names of what we see. To know the names is to enter the enchantment because every reader of fairy tales understands the power of knowing someone or something’s true name. Forests and woods can cast a spell that no other places can – and I want my boys to feel that magic as I have over the years.

As a child I discovered nature both through books (Beatrix Potter and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows were two vital ones for me) and by playing in and exploring the woods behind our house. I lament that my own sons do not have the ability to just roam free in the nature as I did, but I still make the effort to take them out on weekly nature walks and spend time in national parks where they can encounter fish in the streams, hear the piercing cry of a red-tailed hawk in flight, feel moss on their feet, see the sunlight dancing amidst the branches and leaves of the trees, and to learn the names of what we see. To know the names is to enter the enchantment because every reader of fairy tales understands the power of knowing someone or something’s true name. Forests and woods can cast a spell that no other places can – and I want my boys to feel that magic as I have over the years.

I want my sons to pick and taste wild blackberries. To know the feel of acorns and the cool, smoothness of river stones and what it’s like to put one’s hands into the soil. I want them to realize that, while we are not wealthy by any means, we have riches by being able to spend time in such places.

I want my sons to pick and taste wild blackberries. To know the feel of acorns and the cool, smoothness of river stones and what it’s like to put one’s hands into the soil. I want them to realize that, while we are not wealthy by any means, we have riches by being able to spend time in such places.

As Macfarlane wrote in The Wild Places, “Wild animals, like wild places, are invaluable to us precisely because they are not us. They are uncompromisingly different. The paths they follow, the impulses that guide them, are of other orders. The seal’s holding gaze, before it flukes to push another tunnel through the sea, the hare’s run, the hawk’s high gyres : such things are wild. Seeing them, you are made briefly aware of a world at work around and beside our own, a world operating in patterns and purposes that you do not share. These are creatures, you realise that live by voices inaudible to you.”

The Lost Words is a lovely reminder of what we need to remember to value: the words and the natural world they are referring to. There is a beauty and a poetry to the natural world that Macfarlane and Morris capture exquisitely. Our family has developed and nurtured our intense love for words and the wild woods, so this book was a wonderful addition to our collection and will be treasured for years to come.

The Lost Words is a lovely reminder of what we need to remember to value: the words and the natural world they are referring to. There is a beauty and a poetry to the natural world that Macfarlane and Morris capture exquisitely. Our family has developed and nurtured our intense love for words and the wild woods, so this book was a wonderful addition to our collection and will be treasured for years to come.

Dandelion, fern, starling, spores, smoke, feathers are all parts of our lexicon. We have guides for birds, trees, plants and regional animals. Every trip that we go on as a family, we always research where we can spend time in nature and, hopefully, discover animals, plants and birds we don’t normally encounter. Because of me, my family has also begun paying attention to roots, moss, clouds, and rocks.

The Lost Words is a book to be poured over: both the images and poems. They also have continued to inspire my younger son to draw and paint watercolors of what he sees in nature (along with furthering his interest in keeping a nature journal). This book will encourage anyone who reads it to desire to become protector of lost words so that they do not become forgotten and to find an abiding love for nature and spending time in the woods again. This book is magical.

The Lost Words is a book to be poured over: both the images and poems. They also have continued to inspire my younger son to draw and paint watercolors of what he sees in nature (along with furthering his interest in keeping a nature journal). This book will encourage anyone who reads it to desire to become protector of lost words so that they do not become forgotten and to find an abiding love for nature and spending time in the woods again. This book is magical.

“A proportion of the royalties from each copy will be donated to Action For Conservation – the charity that works with disadvantaged children and which is dedicated to inspiring young people to take action for the environment. Macfarlane is a founding trustee. “

“A proportion of the royalties from each copy will be donated to Action For Conservation – the charity that works with disadvantaged children and which is dedicated to inspiring young people to take action for the environment. Macfarlane is a founding trustee. “