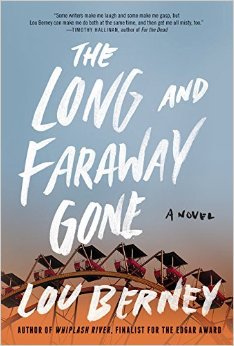

As a Professor of French Literature and a specialist in the nineteenth century, David Bellos is well placed to write about Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel, Les Misérables.

Cover illustration: Jillian Tamki

Cover illustration: Jillian Tamki

He states that many educated readers have never read it because they have heard of it primarily from film and musical adaptations and regard it with snobbish disdain. This is true, to some extent, of me. I have not read it although it was my grandfather’s favourite novel and one of the few books in his house. It’s strange though as I have read Zola, Stendhal and Balzac so I am not sure why I neglected Hugo’s masterpiece. Maybe the title put me off. Resolution for 2017: read Les Misérables.

Bellos, himself, first read it for the strangest of reasons. Embarking on a camping holiday in the Alps, and looking around for a long read, in a light volume, he chanced upon Les Misérables on a shelf. Its many words were printed on ‘Bible paper’ so it would be easy to carry. The trip was aborted by weather and illness so Bellos booked himself into a cheap hotel and lay in bed reading, until he had finished. A similar thing happened to me when I was on a school trip in Italy, aged 18; I read War and Peace.

David Bellos: newyorkcity.eventful.com

David Bellos: newyorkcity.eventful.com

The Novel of the Century, at fewer than 300 pages is, in itself, an undertaking, as Bellos is not only providing a host of details surrounding the penning of the novel but also hoping to show how nineteenth century social politics and societal mores affected Hugo’s ideas. At the same time, parallels are drawn, particularly in attitudes regarding the poor, to post-millennial morals. At times the comparisons feel rather forced but Bellos does encourage the reader to think whether or not plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Hugo, apparently, did not describe the gruesome incidents in his novel although Bellos insists that adaptations often choose to amend this with sensational depictions, such as the working life of a prostitute or the cruelty of a punishment. Bellos sees it as his job, not only to provide a full account of what would have happened, or did happen, in the lower echelons of French society during the post-Napoleonic era but also to show how other artists have developed Hugo’s scaffolding to dramatic effect.

Sub Clara Nuda Lucerna painted by Victor Hgo

Sub Clara Nuda Lucerna painted by Victor Hgo

He is also at pains to match characters and incidents in Hugo’s own life to those portrayed in the novel. Hugo, a serial philanderer – and one who narrowly avoided a court case concerning, Léonie Biard, one of his married lovers – ignores sexual matters in Les Misérables, perhaps, suggests Bellos, because it was a bit too close to his own affairs.

Whilst supplying background, he attacks what he regards as speculation by other researchers and consistently signposts anything that he thinks is impossible to prove but might be worth considering. Bellos is aiming for clarity: almost as if he can feel disparaging scholars peering, at his manuscript, over his shoulder.

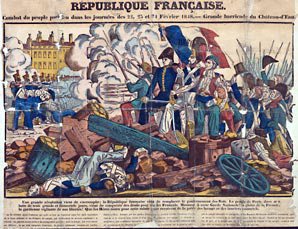

At times he does seem patronising, surveying all from his ivory tower in Princeton, as he explains, “’Revolution’ means a turn of 360 degrees – in car engines, for example”. Hugo’s characters live through a revolution, as did Hugo. He had already finished his first draft of Les Misérables when in February 1848 revolution broke out in Paris.

Bellos identifies the causes as “general desperation of the poor, and a particular political mess”. There had been much republican unrest about the reign of Louis-Phillipe. Having been a peer of the realm under the king, Hugo became, in June, an elected representative of the people. In November Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was elected as prince-president and the Second Republic was established.

Bellos identifies the causes as “general desperation of the poor, and a particular political mess”. There had been much republican unrest about the reign of Louis-Phillipe. Having been a peer of the realm under the king, Hugo became, in June, an elected representative of the people. In November Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was elected as prince-president and the Second Republic was established.

It had been an anxious and fearful time for Hugo but the experience of the riots and the barricades would, eventually, enter the second draft of his epic. Meanwhile he was totally involved as the chief elected politician in Paris. Bellos writes that Hugo believed that if “the plight of the poor could be made less dire, then all that was frightening or bad in the socialist project would vanish”. He was torn between his liberal feelings and his support for order.

But repressive elements were in the ascendant to such an extent that it became a crime to offend the president. Hugo named Louis-Napoléon “le petit” as opposed to his uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte “le grand”. Before long both his sons were in jail and Hugo, with the help of his lover, Juliette Drouet, fled to exile in Belgium. It was not until, in Guernsey, twelve years later, in 1860, that work recommenced on Les Misérables.

One of Hugo’s morals is, as Polonius says in Hamlet, “neither a borrower nor a lender be”. He thought that debt, any debt, was the first symptom of criminality. Characters in the novel who fall into debt, whether they are good or bad, come to a nasty end.

Another important message is about religion. Hugo was not a practising Catholic and he manages, through omission of events such as weddings, to keep churches out of the novel. There is a saintly man, who is a priest, but this is evidenced in daily acts of generosity and forgiveness. Many of Hugo’s friends in Guernsey were vehemently anti-Catholic but Hugo would not agree to rail against religion. Bellos thinks that, for Hugo, “materialism and atheism exacerbate the opposition between the rich and the poor”. Christian faith suggests equality.

A third issue that Hugo addresses is that of women in society. In some notes to himself, he wrote: “as long as women are legal minors, as long as the problem of women remains unsolved, the convent is only a secondary crime. Marriage with God is not a bad deal”. In an early draft of a preface, Hugo wrote, that “the infinite exists … That selfhood of the infinite is God”. He had a teleological view of history: believing in “the future of man on earth, that is to say his improvement in human terms”. Unfortunately, for Hugo, and perhaps for Bellos who is attempting to show how Les Misérables is a novel of the twenty-first century, as well as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most people no longer share this belief.

As the title suggests The Novel of the Century is a labour of love. It is drawn from a prodigious amount of research and is a work of vast ambition. Bellos has so much material that he struggles to interweave it into a coherent unit. Structurally the five parts, broken internally into chapters, are interleaved with interludes. The purpose of these sections seems to be to give further information that just would not fit in anywhere else. The book is dedicated to Bellos’s students; they may wonder why he, who is probably constantly narrowing the focus of their theses, has allowed himself so much leeway.

Works cited

Bellos, A. The Novel of the Century. Penguin Random House. 2017.

An earlier version of this review appeared in the Irish Examiner, page 33 and 34 of the Weekend section on 11 Feb 2017.

Advertisements Share this: