I have said, time and again, that I have a lot to be grateful for to the readers of this blog. Not only do all of you keep me going by reading my posts, commenting on them and discussing them (even going off on tangents!), you also educate me, enlighten me, entertain me—and, importantly, give me recommendations now and then.

Especially over the past few months, I have seen several memorable (and, at least to me, obscure) films that came to my notice simply because readers recommended them to me. The Outrage was recommended by Hurdy Gurdy Man; Neeru told me about Leave Her to Heaven; and CP Rajagopalan mentioned The Secret of Santa Vittoria. Not once, but in two separate comments, which prompted me to hurry up and watch it. And yes, what a film this turned out to be.

The eponymous Santa Vittoria is a small town in Italy where the story opens just before dawn sometime near the end of World War II. The earnest and excited Fabio (Giancarlo Giannini) comes racing to the church, waking up the priest and insisting on ringing the church bells, because there’s such momentous news… when the dazed, sleepy and generally stoic-looking residents of Santa Vittoria gather around in the square, Fabio shares his news: Mussolini is gone. Fascism has ended!

It takes a while, some irritated taunts by Fabio, and the appearance of one of the town’s local Fascists to spur people into action. Even as a crowd goes off, chasing the Fascist around the square, a local townsmen, Bombolini (Anthony Quinn) goes back into the wine shop that he runs along with his wife Rosa (Anna Magnani).

Rosa is really the one who runs the wine shop; when Bombolini and his friends open a bottle to celebrate the fall of the Fascisti, Rosa asks them to pay up. A disgusted Bombolini ends up escaping her eagle eye and filching a bottle from the rack even as he follows his friends out.

Meanwhile, the local Fascists are wondering what to do. The Germans will be arriving soon, but before they turn up, the mood of the locals may turn ugly enough to be dangerous for these fellows. The best course of action, they decide, would be to surrender, on their own terms. Whom will they surrender to, though, is a question they are yet to answer: other than the Fascists, there is no-one in authority in Santa Vittoria.

Little do they know how soon that problem is going to be resolved.

Because, high up (dizzyingly high up) on the water tower of Santa Vittoria—with a wine bottle tucked under one arm, is a very inebriated Bombolini. He’s come up, wine and a bucket of white paint in hand, to erase the huge ‘Mussolini is Always Right!’ he, Bombolini, had painted on that tank years back. He was wrong, oh so wrong, he tearfully tells a harried Fabio, who climbs up the tower to rescue him while all the town’s populace looks on from below.

Fabio, at Bombolini’s instructions, sets about painting over those offensive words, and then starts to get Bombolini off the tower. In the process, there’s a slip and both of them nearly plummet to their deaths. Bombolini, wine-befuddled, clings to whatever support he can find and decides he’s not going to budge. No, never, come what may.

A desperate Fabio, therefore, looks for a way to shore up Bombolini’s flagging spirits—and all he can think of is to encourage the crowd to chant “Bombolini! Bombolini!” This eventually has the desired effect: Bombolini, chest puffed up, starts to descend once more…

… and, at the City Hall overlooking the piazza, the Fascists hear the roar and come to the conclusion that the townspeople have selected Bombolini to be their leader. That idiot? But yes, that’s right, isn’t it? An idiot is best! An idiot will, in fact, be perfect, at least from the point of view of the Fascists.

So when Bombolini, carried along on the shoulders of a laughing, enthusiastic crowd ends up in front of the City Hall, the Fascists come out, swiftly (by slinging a whacking big medal around his neck) proclaim him Mayor of Santa Vittoria, and formally surrender to Bombolini.

Bombolini is too drunk (and anyway, even when he’s sober, he’s never really thinking straight) to grasp the ramifications of this. He happily accepts, happily orders the arrest of the Fascists, and then happily leads the entire mob back to his wine shop.

When a furious Rosa (she and her daughter Angela are among the few people who haven’t turned out to see this spectacle) refuses to let Bombolini and his rowdy crowd in, he leads them to break down the gate…

…with predictable results. Rosa spends much of the evening thrashing her husband with a rolling pin and wishing she’d never married him. She ends by upturning a colander full of spaghetti over Bombolini’s head.

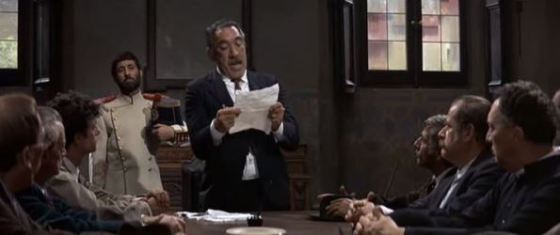

When he’s somewhat more sober, though, Bombolini is given a few tips—including a copy of The Prince by Machiavelli (“Eh? Who?”) by Fabio and another somewhat more level-headed Santa Vittorian, Bombolini gets down to business. Casting aside his initial decision to resign with ‘dignity’ (“Take this job and shove it up your a**”), Bombolini sets about setting up a Grand Council. Fabio, who studies far away at university, is the only one on it who’s passed fourth grade.

Bombolini and his Grand Council set about working, doing this and that. Nobody—least of all Rosa, who has a very poor opinion of her husband—is impressed. Meanwhile, Fabio has gone back to the University (to the distress of Angela, who dramatically tells her disgusted mother just how she feels about Fabio, and how, at sixteen—“I have breasts!”—she is woman enough to know what this feeling is).

Fabio soon comes hurtling back to Santa Vittoria, bringing with him momentous news: the Germans are headed here. They will arrive on the 17th and are coming with the express purpose of taking away all of Santa Vittoria’s famous wine.

Panic ensues. How much wine does reside in Bombolini’s vast cellars, after all (the town supplies wine to the Cinzano company, so this quantity is not to be scoffed at)? The wine master comes up with the almost-precise figure of 1 million, 3,17,000 bottles. More or less.

More than a million and a quarter? They can’t let the Germans take all of that away! Bombolini and his men wrack their brains, trying to think of a way to hide the wine. It’s not easy to find a good hiding place for over a million bottles of wine.

The answer eventually comes from an unexpected quarter. Carlo Tufa (Sergio Franchi) is a wounded soldier who deserted from the Italian Army and returned to Santa Vittoria when Mussolini’s regime collapsed. He’s been nursed back to health by another returnee, the glamorous Contessa Caterina (Virna Lisi), who lived in Rome till recently and has come back after being widowed.

While the Contessa and Tufa begin an affair, Tufa makes a suggestion to Bombolini: the townspeople should form bottle lines (somewhat like bucket lines) from the town’s cellars to the old Roman cave across the hill, and shift all those bottles to the cave.

Further discussions ensue: won’t the Germans become suspicious if they find not a single bottle of wine in Santa Vittoria (which, surrounded as it is by vineyards, is quite obviously an important wine-producing town)? All right, we will retain 10,000 bottles for the Germans to confiscate. No, no, that’s too little; it’ll be apparent that this is just a bait and that more is stashed. After much debate, a consensus is reached: only 1 million bottles will be hidden away. The rest, 3,00,000-odd, will be left in the town’s cellars for the Germans to find.

So Santa Vittoria’s bottle line, with just about everybody old enough and sturdy enough to stand and pass on a full bottle of wine, gets into action. For days, well into the night, working in shifts and stopping only for very brief breaks, the townspeople transport 1 million bottles from the cellars to the caves. At the caves, the bottles are stacked and finally, when every last bottle is in place, bricked up. Unless you know what lies behind that seemingly ancient wall, you’d never guess this wasn’t just part of the cave itself.

Sure enough, right on schedule, the Germans arrive in Santa Vittoria. Captain von Prum (Hardy Krüger) is the officer in charge, and he seems like a tolerable enough man: he has a sense of humour (as is obvious in his interactions with Bombolini), and he doesn’t appear to be at all ruthless Nazi.

But, even as Bombolini is beginning to heave a sigh of relief and imagine he (and Santa Vittoria, and most of all the wine) are safe, things begin to happen. Von Prum spots the Contessa and is immediately attracted to her. Meanwhile, relations between Bombolini and Rosa—which seemed to be improving because of the shared stress of shifting the wine—go haywire again when Rosa finds Angela in bed with Bombolini’s protégé, Fabio.

What happens eventually? Does von Prum discover the wine (does he even realize there is wine to be discovered?) What of Bombolini and Rosa, Angela and Fabio, the Contessa and Tufa? What of Santa Vittoria and its secret?

What I liked about this film:

The blend of tones and elements. The Secret of Santa Vittoria starts off seeming like a comedy, and pretty much remains one till about halfway through the story. But then, even though it retains the humour to some extent, it also becomes sombre, reminding us that this is after all during World War II. There’s a war on, and the enemy is notorious for its brutal ways in getting what it wants. There is the disturbing reality that von Prum, for all his otherwise amiably businesslike way of dealing with Bombolini, can be pretty nasty when he doesn’t get what he wants—whether it’s a million bottles of wine or a beautiful woman he desires.

The balance is excellent. The comedy doesn’t go overboard and become outrageously funny (a lot of the comedy, in fact, draws from the dialogue, which is deliciously sarcastic at times). And when the more sober elements of the story start cropping up, they are presented in such a way that while you can see the somberness of them, the way they fit in and help add that touch of verisimilitude to the story.

Ultimately, what really works very well in this tale is the way it puts across the message of a community coming together to preserve what is its own, and protecting it in such a way that it helps build the community’s strength. While, at the same time, helping individuals grow and develop, too.

What also stands out is the acting, especially of Anthony Quinn and Anna Magnani, both of whom are simply fantastic as Bombolini and Rosa. (Rosa, by the way, gets some of the best dialogues in the film by way of taunts directed at her husband: “Why would they [the Germans] put a pistol to your head? The whole world knows Bombolini’s brains are in his a**!”)

What I didn’t like:

Nothing, really. While I would’ve loved the comic nature of the beginning to have been retained all through the film, without the little wrinkles that creep in, reminding us of the bitter truth—I didn’t really mind that that comedy did get diluted. This, after all, was wartime. And can war ever be completely without the truth peeking in?

Worth a watch.

Advertisements Share this:- More