I fell in love with Julia Child when everyone else my age did, upon watching Julie and Julia, the excellent film with Meryl Streep, Amy Adams, and Stanley Tucci. (I include this list on the chance that you are like me and have a middle aged housewife’s retention of names.) I then delved into The French Chef, Julia’s excellent television program; watching her make bouillabaisse was one of the foundational moments of my comedic life. You have Julia, six feet tall, with a button-down shirt and an apron, speaking in her falsetto, cultured voice, slamming a meat cleaver into masses of fish. “It’s really very – ” slam slam “ – easy to make this traditional – ” slam whack “ – soup, which you can find in the south of France…” WHACK!

I suppose you really do have to be there.

But what Julia gave us was an enthusiasm for cooking, particularly because she was able to show us how to do it in exacting detail without seeming like a taskmaster. She could flip an omelet on her program and it would go all over her stovetop. “You, alone in the kitchen…Who’s to know?” She’d piece it back together and keep on going. Of course, she’d get all the others perfectly right, and there might be this little suspicion in the back of your mind that maybe she missed that one on purpose, but really, she doesn’t make any production out of her mistake. She suavely goes on, unfazed, in love with the camera and all of the people behind it.

That was the real trick about her, I think. She loved people; she was receptive.

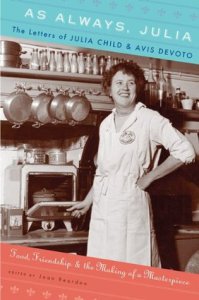

As Always, Julia, a selection of letters, shows you just how lovely a person Julia was in private as in public. In private, she’s witty, acerbic, and deeply loving – not to mention an abiding perfectionist. There’s also quite a lot that you did not expect to know. Julia delicately couches the effects of all that French food on her digestive system upon entering that country – a thunderous upset akin to her experiences with the amoebic dysentery she got in China during WWII (43-44). While living in Marseille, Julia describes the pleasures of naked sunbathing on their terrace there (150). And Paul, the sainted husband so brilliantly portrayed by Tucci in the movie, was occasionally known to go on severe cleaning-out binges; one such episode resulted in the elimination of their marriage license (77). (Which goes to show that their marriage was on extremely solid ground.)

As Always, Julia, a selection of letters, shows you just how lovely a person Julia was in private as in public. In private, she’s witty, acerbic, and deeply loving – not to mention an abiding perfectionist. There’s also quite a lot that you did not expect to know. Julia delicately couches the effects of all that French food on her digestive system upon entering that country – a thunderous upset akin to her experiences with the amoebic dysentery she got in China during WWII (43-44). While living in Marseille, Julia describes the pleasures of naked sunbathing on their terrace there (150). And Paul, the sainted husband so brilliantly portrayed by Tucci in the movie, was occasionally known to go on severe cleaning-out binges; one such episode resulted in the elimination of their marriage license (77). (Which goes to show that their marriage was on extremely solid ground.)

Of course, Julia had to be writing to somebody all that time, and anyone who’s seen the movie upwards of twenty times knows immediately who it was. Avis DeVoto answered Julia’s letter praising Avis’ husband’s article on the relative quality of cooking knives found in America; soon they were passing letters back and forth, Julia sending Avis knives, cookery, cookbooks, and other ephemera, and Avis sending American ingredients, books, articles, and her own brand of wit back.

Over the course of reading this 399-page tome, I got to know not only Julia better, but also Avis. Avis’ mind roves intellectually; she knows many important people in her sphere of influence: writers, politicians, and, most importantly in this context, publishers. She ends up working for Harper’s for a time, and manages then to get an in with Knopf, the company that eventually printed Julia’s cookbook. Avis, though, was more than this paragon and this mover-and-shaker. She rants against dishwashers for being shoddy, but later praises hers for doing such a good job (I can only conclude she bought a radically different model). She goes into a flurry of hustle and bustle, then comes home and enjoys her domestic bliss. But not for too long – after a certain point she is tired of being The Housewife, and decides to put her feet up for a couple of days. And when her beloved husband dies, she is disconsolate. It’s not like she weeps through her letters and makes a big production of her grief: Avis describes how she feels in pared-down prose and hits you where you live. After his death, Avis mentions him every now and then, wondering what he would have thought or would have said.

Over the course of reading this 399-page tome, I got to know not only Julia better, but also Avis. Avis’ mind roves intellectually; she knows many important people in her sphere of influence: writers, politicians, and, most importantly in this context, publishers. She ends up working for Harper’s for a time, and manages then to get an in with Knopf, the company that eventually printed Julia’s cookbook. Avis, though, was more than this paragon and this mover-and-shaker. She rants against dishwashers for being shoddy, but later praises hers for doing such a good job (I can only conclude she bought a radically different model). She goes into a flurry of hustle and bustle, then comes home and enjoys her domestic bliss. But not for too long – after a certain point she is tired of being The Housewife, and decides to put her feet up for a couple of days. And when her beloved husband dies, she is disconsolate. It’s not like she weeps through her letters and makes a big production of her grief: Avis describes how she feels in pared-down prose and hits you where you live. After his death, Avis mentions him every now and then, wondering what he would have thought or would have said.

Avis also wrote, “I like every part of growing older except what happens to your feet” (67).

Of course, there’s a lot about cooking in the letters, a lot about current events, a lot about what it’s like to live abroad and to live in Cambridge. One thing I noticed over and over, though, didn’t seem to have much to do with what we think of Julia and Avis.

It’s the words “special problem,” “special friend,” “special kind of life.”

They never use the word gay. And they are nothing but sympathetic to the people they know who are either in the closet or living with ‘friends.’

There’s the man who has never admitted the truth to himself with a wife gripping onto her life with both hands; there’s the man in denial but who marries anyway. Avis speaks about the first with pity (113) and with cautious hope for the second (248). It’s an odd contradiction, and seems to show that in the 1950s it was permissible to be a gay man, so long as society knew you were married. Being legally bound to a woman was safer, perhaps, and held the possibility for a close friendship, if not a very intimate one.

As for the lesbians they knew, it seemed to be less perilous to remain unmarried, living with a woman ‘friend.’ Lesbians are described as being courageous, as having the fortitude to go against the grain and do as they liked. But then, it has always been less threatening to have lesbians in a society than to have outwardly gay men. [Insert a very long opinion piece of specific social commentary, which I’m not doing because we all have to sleep sometime.] It was quite gratifying to see that neither of them were above gossiping about who went out with who – “Interesting your seeing May Sarton and Cora Du Bois dining together. Hope they aren’t two-timing their friends” (Julia, 294).

In the end, the book is a great comfort, to see great achievements unfolding, to see a friendship grow, and also to note that each woman despaired of her typing skills, sometimes spelling a word wrong and immediately typing it again to get it right. It is in no small way remarkable that they struck up a profound and involved friendship, only meeting each other after three years of correspondence.

In the end, the book is a great comfort, to see great achievements unfolding, to see a friendship grow, and also to note that each woman despaired of her typing skills, sometimes spelling a word wrong and immediately typing it again to get it right. It is in no small way remarkable that they struck up a profound and involved friendship, only meeting each other after three years of correspondence.

Through it all is the behemoth, the cookbook. At the beginning, Julia predicts that cooking and teaching “will keep me busy well into the year 2,000” (10). She died in 2003, two days before her 92nd birthday; there is no indication that her prediction fell short of the mark. As for Avis, she continued to work more or less behind the scenes, enabling others and having a good time whenever possible. Strangely enough, Avis’ name does not appear on the Wikipedia page for Mastering the Art of French Cooking. I wonder if that is how she would have wanted it.

Advertisements Share this: